After David Bowie died earlier this year, I listened to his final album, “Black Star.” And I cried.

In the album, Bowie took us on a journey through the fever dreams and delusions caused by chemotherapy. One of my best friends died of brain cancer in our early '20s, and Bowie helped me to understand my friend’s mental confusion, and the often prophetically beautiful insights about the world that he shared with me from his deathbed.

The passing of Prince is different. It feels like the death of my youth. Those of us -- the “hip hop generation” -- who came of age in the '80s and '90s have lost another one of our icons. Michael Jackson is gone. Prince is now gone. Who remains from that era?

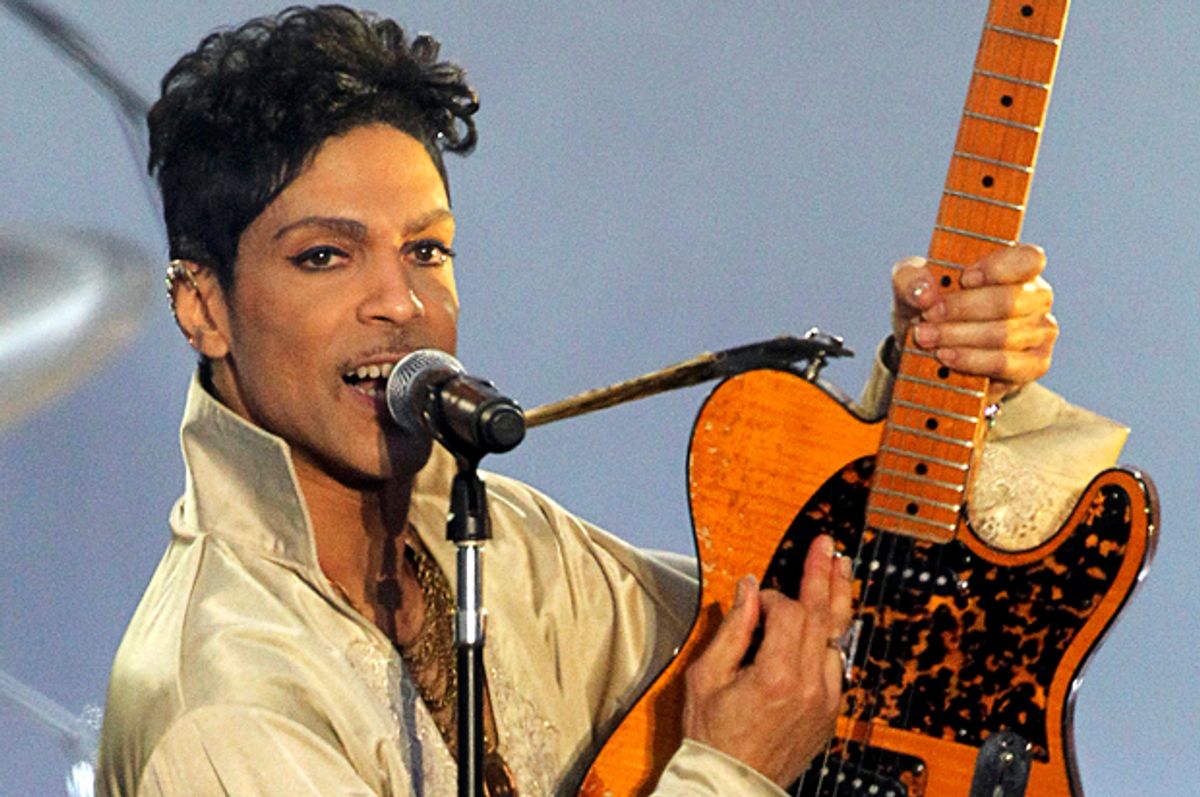

Prince’s legacy will be reflected upon in many ways. Of course, there will be books written about his music and his life. He was a transgressive race- and gender-bending figure who once sang, “Am I black or white? Am I Straight or gay?” Prince was Afro-futurism in the present. He was a trickster figure. Like George Clinton and Sun Ra before him, he was also one of the leaders of what I like to call “the cult of the black weirdo.” It is in this role that I will miss him the most.

The persona “Prince” gave Prince Rogers Nelson the freedom to be himself. Many black men have internalized the White Gaze, seeing themselves and their masculinity through a lens that returns a distorted view of their own personhood. Some black men and boys assess their racial and gender authenticity relative to success in sport, their humanity reduced to the physical. Others have taken the mass media’s narrative of black hyper-thug masculinity, as portrayed in commercial rap and other types of popular culture, to be a type of role modeling behavior and a measuring stick for “real” and “authentic” black manhood.

American popular culture (and the collective subconscious it represents) both historically, and in the present, stereotypes black men as superhuman, “angry,” mean, criminal “super predators,” “black beast rapists,” as natural criminals with poor impulse control and out-of-control libidos. Prince defied all of those ugly distortions of what it means to be black and male in America.

Celebrities are projections of their fans’ hopes, wishes, dreams, and fantasies. They are also -- and this is especially true when they pass away -- focal points for our memories, our personal stories, for generational experience.

I will personally remember Prince as the “light-skinned” black dude that even the brown- and darker-skinned brothers and sisters could admit they liked back in the 1980s. Even at house parties where folks were posturing to N.W.A., Wu-Tang, Biggie and Nas, no one would complain if Prince’s music were played to close out the night. I smile as I think about how, on a bet, I went out as Prince for Halloween -- with wig, makeup and full regalia.

Prince provided the music when George Lucas married Mellody Hobson in Chicago. It was a great day as I got to see Lucas, one of my personal heroes, in person; like many of my neighbors, I strained my ears to hear a free concert provided by Prince from a few blocks away. I remain unsure if I actually heard Prince play “Purple Rain” that night, but I certainly imagined that I did.

As a member of the hip hop generation, I know I am not alone in reminiscing about graduating out of the awkward high-school groping and sex to a soundtrack by Al B. Sure and Jodeci, and finally fucking like an adult while Sade, Anita Baker, D’Angelo, and, yes, Prince played in the background.

Because he was a great artist, Prince also had a good number of misfires and outright failures. To wit: “Grafitti Bridge” is a horrible film. The heckling by the audience I saw it with during the summer of 1990 merited a Comedy Central special or "Mystery Science 3000" episode. Like other great artists, Prince was not afraid to fail, gloriously and with confidence.

I keep hoping that this is all an elaborate gag or an exercise in performance art; that Prince, the trickster musical genius, is laughing at us all. But he is gone, now likely playing a song with David Bowie in some alternate dimension where all of the beautiful geniuses go. Ziggy Stardust is finally together with Alexander Nevermind. If we close our eyes and listen really closely, I bet we can hear the duet.

I will not say goodbye to Prince, but rather in the spirit of his eccentricities, genius, and artistry, I offer an “until next time.”

Shares