When Donald Trump announced his candidacy for president on June 16, 2015, almost no one predicted that he would become the leading Republican candidate, let alone the party's nominee. As the statistics guru Nate Silver told Anderson Cooper in September, Trump’s chances of becoming the Republican nominee were about 5 percent. And two months later, Silver “explained that Trump’s national following was about as negligible as the share of Americans who believe the Apollo moon landing was faked.” Yet as of this writing, it’s quite possible that, come January 2017, Trump could be handed the nuclear codes.

How did this happen? Much of Trump’s success stems from his unique ability to manipulate the very same tendencies that lead many people, most notably on the political right, to embrace faith-based religion. He instills fear in his listeners and then offers them salvation in a new, remade America, if only they’ll accept him as president. While Trump himself doesn’t appear to be a sincere Christian — for example, he once mispronounced “2 Corinthians” before an audience at Liberty University — a new religious system of sorts has grown around his “cult of personality,” which Trump developed as a real estate tycoon and loud-mouthed buffoon on his reality TV show. Call this new religion Drumpfism, after the Trump family’s original last name: Drumpf.

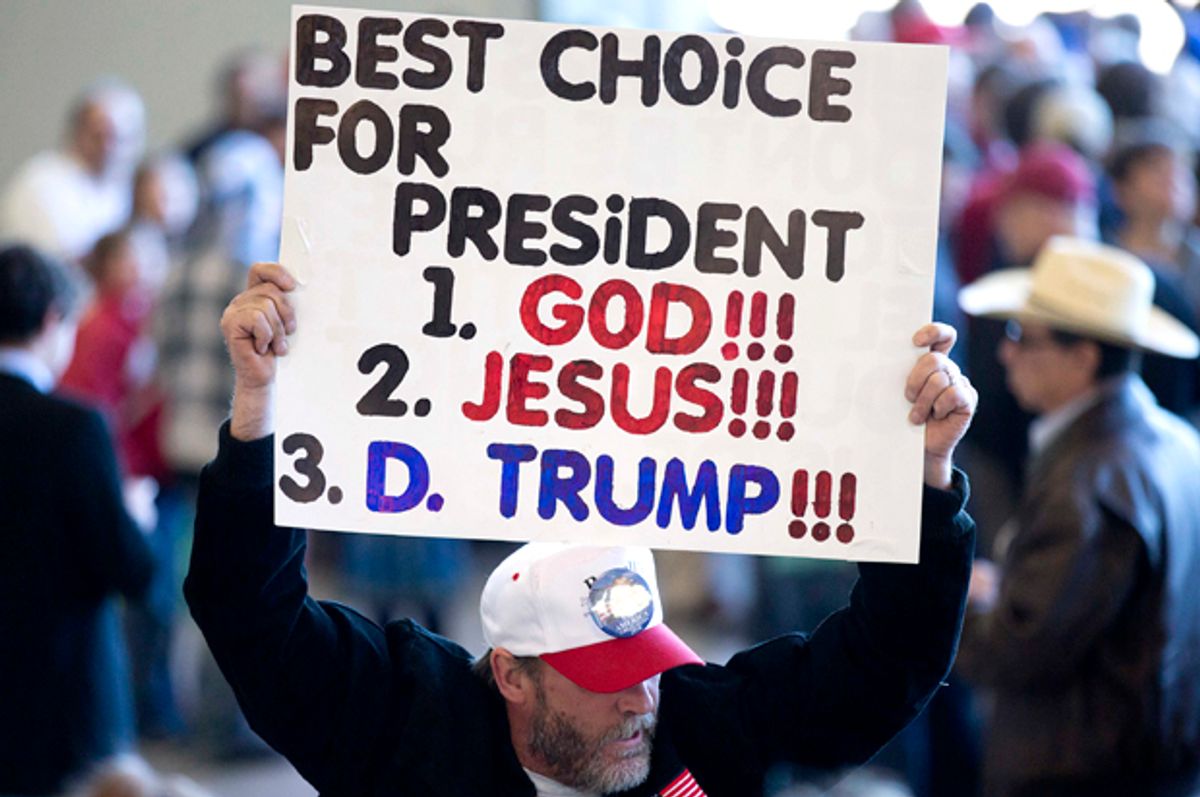

The appeal of Drumpfism is its similarity to Christianity, the predominant religion among American conservatives. For example, at the heart of Drumpfism is a demand to have faith in the impeccable judgment and sagacity of Donald Trump. Rather than present verifiable evidence to corroborate his claims, Trump habitually implores his audience to “believe me,” a locution that translates as “take a leap of faith and simply trust in my abilities.” As the right-wing Fox News commentator Charles Krauthammer puts it, Trump is “running a campaign on belief.” When it comes to building a “beautiful wall” along our southern border or defeating China, Trump’s answer is essentially identical to what Christianity tells its followers: “Have faith in God [i.e., Trump] and don’t ask too many questions.” In a conversation with his disciple Thomas, of “doubting Thomas” fame, Jesus says: “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” This is the central epistemology of Drumpfism, and it’s proven to be quite effective among a segment of the American population.

Turning from faith in Trump to Trump’s divinity, the persona that he presents to the public exhibits many of the same attributes as the Christian God. For example, Trump is an authoritarian leader who demands absolute obedience from his subjects, and in this way he resembles the “celestial dictator” of Christianity (to quote the late Christopher Hitchens). Consider an exchange between Trump and Fox News’ Bret Baier during a Republican presidential debate. “Just yesterday,” Baier said, “almost 100 foreign policy experts signed on to an open letter refusing to support you, saying your embracing expansive use of torture is inexcusable. General Michael Hayden, former CIA director, NSA director, and other experts have said that when you asked the U.S. military to carry out some of your campaign promises, specifically targeting terrorists’ families, and also the use of interrogation methods more extreme than waterboarding, the military will refuse because they’ve been trained to turn down and refuse illegal orders.” Trump’s response? “They won’t refuse. They’re not going to refuse me,” to which he added, “I’m a leader. I’m a leader. I’ve always been a leader. I’ve never had any problem leading people. If I say do it, they’re going to do it. That’s what leadership is all about.”

Trump also conveys a sense of omnipotence, or an ability to accomplish virtually any task, no matter how formidable. In some cases, Trump claims not only that he can solve a particular problem, but that he’s the only leader who can solve it. For example, after forming a presidential exploratory committee early last year, Trump released a statement in which he said, “I am the only one who can make America truly great again!” (Exclamation point in the original.) Similarly, after an Easter Sunday attack by the Taliban that killed dozens of Christians in Pakistan, Trump tweeted: “Another radical Islamic attack, this time in Pakistan, targeting Christian women and children. At least 67 dead, 400 injured. I alone can solve.” On yet another occasion, he tweeted that he is “the only one who can beat Hillary Clinton,” despite polls that consistently show Clinton beating Trump in a general election scenario. From Trump’s perspective, if he’s not an all-powerful being, then he is at least uniquely capable of restoring America’s greatness, overcoming Islamic extremism and defeating his political rivals. This sense of being completely unique among one’s peers — a kind of messianism — is a topic to which we’ll return momentarily.

Not only is Trump authoritarian and omnipotent, though, he also presents himself as omniscient, or all-knowing. For example, after the 2016 terrorist attacks in Brussels, Belgium, Trump claimed that he “was the one who predicted this was going to happen.” He even declared to Fox News that he “knew more about Brussels than Brussels knew.” And in response to criticism of his claim that “thousands and thousands” of Muslims in New Jersey celebrated the 9/11 attacks, Trump confidently announced that he has “the world’s greatest memory. It’s one thing everyone agrees on.” With respect to his intelligence, Trump once assured his followers (back in 2013) via Twitter that “my IQ is one of the highest — and you all know it!” Even when Trump is forced to acknowledge that he’s ignorant about a particular topic, he still manages to perpetuate a God-like sense of superiority. When the conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt, for example, pressed Trump on the difference between Hezbollah and Hamas, Trump initially admitted that he doesn’t know. Hewitt then asked, “So the difference between Hezbollah and Hamas does not matter to you yet, but it will?” To which Trump confidently replied, “It will when it’s appropriate. I will know more about it than you know, and believe me, it won’t take me long.” Once again, Trump demands faith from his listeners while asserting his future omniscience about a topic that every presidential candidate should already understand.

Trump also fancies himself as somewhat infallible, often doubling down on false claims even after they’ve been shown by independent, nonpartisan sources to be inaccurate. For example, Politifact rated Trump’s assertion that a large number of Muslims celebrated in New Jersey after 9/11 as “Pants on Fire” — the worst rating possible. And Politifact wasn’t the only organization to weigh in on the matter and conclude that Trump uttered a falsehood. Even the mayor of Jersey City at the time responded that Trump either “has memory issues or willfully distorts the truth.” Rather than acknowledge an error, though, Trump intransigently stood behind his claim by asserting the superiority of his memory and lobbing ad hominem attacks at Politifact, calling them a “left-wing group” that is “very dishonest.” Incidentally, Politifact awarded Trump their dubious “Lie of the Year” award for this statement, as well as two others that received “Pants on Fire” ratings. As far as the religion of Drumpfism is concerned, Trump’s remarks are always correct, even when the facts unambiguously say otherwise.

But the most intriguing similarity between Drumpfism and Christianity pertains to their shared apocalyptic narratives, in which great catastrophes are followed by a new, better, purified world. In the case of Drumpfism, these catastrophes are already happening, and they could become far worse if Clinton ends up in the Oval Office. Thus, Trump has declared that “Our country is going to hell.” Why? Because of immigration from Mexico (rapists) and Syria (terrorists); changing demographics (white people could become a minority race); the Islamic State and al-Qaeda; the menace of China; and political correctness (which got Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill). As Trump has stated, the other Republican candidates “won’t take us to the promised land” — an overtly prophetic term — whereas Trump promises to “make America great again.” He can, and desperately wants, “to save the country.” How? By using his God-like attributes to accomplish magnificent feats of unprecedented greatness, such as building a giant wall between the U.S. and Mexico; banning all Muslims from entering the U.S.; targeting the family members of terrorists (and perhaps nuking ISIS); punishing China; and making it acceptable once again to use language that’s offensive to women, minorities, and other groups.

As Chip Berlet notes in a Fortune magazine article called “Why People Love Trump’s Apocalyptic Vision of America,” a confluence of societal factors have fostered a pervasive sense of apocalyptic urgency among the largely uneducated white working class, who are now looking for a strong messianic figure to “save” them from changes that they perceive as catastrophic to their beliefs, country, and very identity as white Americans. Trump somehow fits the mold of this messianic leader — indeed, he very likely suffers from a “messiah complex,” along with narcissistic personality disorder and grandiose delusions — and this fact is a major reason that Trump has ascended to such great heights of popularity within the Republican Party. Trump is the messiah that America needs to restore our greatness after eight years of a black president who Trump has repeatedly claimed was born in Kenya.

The great irony of this entire situation is twofold. First, not only did Trump once fail to say “2 Corinthians” correctly, but he was also repeatedly unable to answer the question, “What is your favorite Bible verse?” Later, Trump claimed that his favorite part of the Bible is “Proverbs, the chapter ‘never bend to envy,’” which is a nice bit of aphoristic wisdom, for sure, but it’s not in what Christians perplexingly call the “Good Book.” Despite such cringe-worthy missteps, Trump has insisted — in typical Trump fashion — that “Nobody reads the Bible more than me,” and he’s also managed to get the endorsement of a major evangelical figure, namely Jerry Falwell Jr. of Liberty University. The point is that if Trump is religious at all, he’s a Drumpfist, not a Christian.

Second, what is perhaps most amusing about this situation is that few of Trump’s followers have considered the possibility that Trump is one of the “false prophets” mentioned in the New Testament. After all, just look at Trump’s God-like, messianic self-importance. As Jesus said to his disciples after being asked, “What will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?,” “Watch out that no one deceives you. For many will come in my name, claiming, ‘I am the Messiah,’ and will deceive many.” Trump has all but explicitly declared that he is the messiah, opting instead for slightly less direct statements like: “I will be the greatest jobs president that God has ever created,” “I am the most successful person ever to run for president,” “Nobody’s ever been more successful than me,” “I am more presidential than anybody, other than the great Abe Lincoln,” “I am the most humble celebrity,” “I am the least racist person you will ever meet,” “Nobody has more respect for women than I do,” and finally, as quoted above, “I am the only one who can make America truly great again.” Given that some 41 percent of Americans — not Christians, but Americans — believe that we’re living in the end times, it’s a wonder that more people don’t see Trump himself as a fulfillment of prophetic scripture.

All religions are dangerous, because the epistemic attitude of faith compromises the link between our beliefs about reality and what reality is actually like. But the new religion of Drumpfism is especially dangerous. Not only has it proven itself to be unusually resistant to the facts — as Trump’s “Lie of the Year” award confirms — but Trump’s rhetoric has incited violence, hatred and intolerance, as well as instilling an alarmist apocalypticism among the frightened, uneducated, poor, white working class. This is a recipe not only for Trump to wiggle his way into the White House, but for a general election in which Trump loses to leave the country dangerously divided.

Shares