Morrissey may never agree to a Smiths reunion, but he's still very proud of the band's legacy—especially as "The Queen Is Dead" heads toward its 30th birthday in June. "I would like to congratulate the Smiths, and also Stephen Street, and also Rough Trade Records for 30 fantastic years of sales for 'The Queen Is Dead,'" he recently wrote via his mouthpiece website, true-to-you.net. "We have always been gagged, of course, but certain recordings rise with time, and 'The Queen Is Dead' and also [1985's] 'Meat Is Murder' both had the courage to put the fullest meaning of British life into words and music." After noting how relevant the album's themes still are to modern-day England, he then asked people to purchase the title track of "The Queen Is Dead" in the last week of May—to get it back into the U.K. charts—and got in a small dig at record companies. "It would not quite be the Smiths if not classically ignored by the dried-out lawns of the establishment. I urged Warner UK to issue a special 'The Queen Is Dead' single release for the first week of June ... but ... brick wall."

Ten days after this charmingly churlish rant, Morrissey outdid even himself, and posted a statement in which he denied being a part of the 2016 Chicago Riot Fest, even though he was announced as one of the upper-tier acts just days before. (As of press time, that matter is still unresolved, and it's unclear if he is or isn't playing the festival or what exactly his message meant.) It was a quintessential Morrissey move, and just the latest example of him being a consummate provocateur, someone ill at ease unless he's rattling the status quo. While in the Smiths, this penchant for provocation could be malignant; for example, a memorable 1985 Melody Maker interview (understandably) spawned accusations of virulent racism. However, from a musical standpoint, Morrissey's first finest moments as a lyrical agitator came on "The Queen Is Dead."

The trick is, he improved upon the stridency of "Meat is Murder"—a record with a graphic condemnation of animal slaughter and a thinly veiled account of school abuse, among other things—by embracing more sophisticated commentary. Frequently, this was tethered to the byproducts of fame. "I Know It's Over" is self-flagellating and frustrated by a nagging perception of low self-worth ("'That's why you're on your own tonight/With your triumphs and your charms'"), while "Bigmouth Strikes Again" is equally angst-ridden over things that shouldn't have been said. "Frankly, Mr. Shankly," meanwhile, drips with condescension and sarcasm—"Oh, I didn't realise that you wrote poetry/I didn't realize you wrote such bloody awful poetry, Mr. Shankly"—which supports the rumor it referred to Rough Trade label founder Geoff Travis, with whom the band was feuding. By toning down the hyperbole—and upping the incisiveness and nuance—Morrissey was more effective at getting his point across.

Yet he was smart enough to realize that the downsides of fame are only interesting to a small segment of the population, which is why much of "The Queen Is Dead" had a personalized (and politicized) slant. Instead of wallowing, he crafts a mythology around himself—or the character he's playing on the album—bit by bit: He fashions himself a permanent outsider on "Cemetry Gates" ("Keats and Yeats are on your side/While Wilde is on mine"), identifies with the Shakespearean romantic trope of death-from-love ("There Is A Light That Never Goes Out") and tackles the one-two punch of persecution and feeling misunderstood ("The Boy With The Thorn In His Side"). Plus, "The Queen Is Dead" has its levity: "Vicar In A Tutu" reads like a Shel Silverstein poem (despite the serious subject matter: a man of the cloth who favors dance wear), while the title track features a wry gag about lack of musical talent.

The song "The Queen Is Dead" ranks up there with the Smiths' finest moments. On the surface, it's a song conflating criticism of the royal family with expressions of abject loneliness and despair. Dig a little deeper, and it's an elegy for England itself, and all the ways the country's ingrained power structures—church, pubs, state—destroy individuals. This assertion is supported by Tony Fletcher's meticulous Smiths bio, "A Light That Never Goes Out," which notes that in the mid-'80s, England was facing "catastrophic levels" of unemployment, unions losing power, and a society where "minimum-wage labor replace[d] former job security for those who could even find the work." In addition, "multiculturalism, sexual permissiveness, gay rights, and progressive education were all under attack," while "locally elected left-wing councils were being abolished, spending on the welfare state reduced, [and] government-owned industries privatized." In conclusion, "'The Queen Is Dead' made almost no reference to any of this, and yet it somehow acknowledged all of it, and that was no small achievement." What Morrissey didn't say, in other words, made the song a triumph.

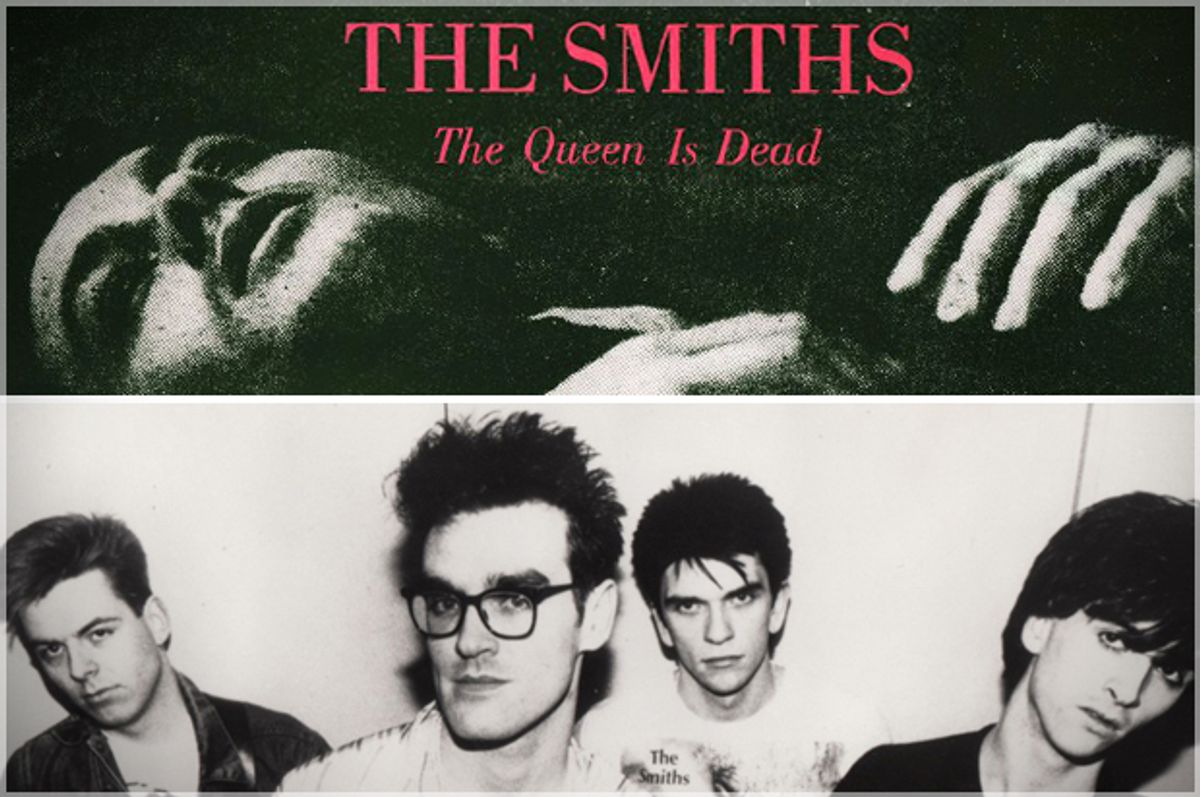

Still, it's a mistake to think that Morrissey was the only one steering this record to greatness. In fact, "The Queen Is Dead" is the most cohesive musical statement put forth by the Smiths' instrumentalists: guitarist Johnny Marr, bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce, as well as studio compatriot/engineer Stephen Street. (Remarkably, this happened although Rourke was dealing with a heroin addiction that ended up causing him to get kicked out of the band for a spell after the album was done.) "The Queen Is Dead" feels slightly phase-shifted from then-trends (cf. well-wrought pop with a manicured '60s influence) and unapologetically nostalgic. For example, the strings and flute on "There Is A Light That Never Goes Out," courtesy of an Emulator sample keyboard, are delightfully syrupy.

Morrissey too comes into his own as a vocalist. Although "Cemetry Gates" contains vestiges of his youthful yelp, he settles into a dynamic, adult singing approach: a Rat Pack croon steeped in conspiratorial desperation, anguished gnashing of teeth and impertinent bite. Above all, "The Queen Is Dead" possesses exquisite sonic balance, where no one part or person (yes, even Morrissey) dominates. Rourke's cowboy-loping bass lurking below "Never Had No One Ever" and the burbling backbone of "Cemetry Gates" fit like a glove, while Joyce proves himself a versatile drummer adept at cheeky swing ("Frankly Mr. Shankly") and rockabilly ("Vicar In A Tutu"), as well as torchy ballads ("I Know It's Over"). And after the guitar turbulence of "Meat Is Murder," Marr finds his comfort zone by carving out sturdy-but-delicate riffs—as heard on the galloping strums of "Bigmouth Strikes Again," the oceanic, ornate "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others" and especially the wistful "The Boy With The Thorn In His Side"—edged with a chiming, lighter touch. It's a style he'd refine and perfect in the subsequent years and with other artists.

Post-"The Queen Is Dead," the Smiths lasted only a little over a year more, as Marr left the band prior to the release of 1987's "Strangeways Here We Come." (In fact, that record emerged posthumously.) That the Smiths imploded so soon after a creative high point helped the record develop a mystique that still endures. And live, both Morrissey and Marr still cycle a handful of Smiths songs in and out of their setlists. For the latter, one of the mainstays is the title track of "The Queen Is Dead." (Recently, it's been paired with a doctored photo of Queen Elizabeth flipping the double bird.) This song in particular has only grown more tangled and powerful with age. The drums explode like flashpots, while the guitars are more of an electric squall, a collision of pent-up anger, frustration and loneliness. The "The Queen Is Dead" LP has maintained its emotional punch and relevance—an inhabitant of its own singular universe which resonates far and wide.

Shares