Donald Trump is the most disliked national politician in America. Hillary Clinton isn’t much far behind. For the past twelve years, two French mathematicians, Michel Balinski and Rida Laraki, have been studying presidential elections in the U.S. The fact that “Trump versus Clinton will almost surely be the choice this November,” they observe, is the result of the totally absurd method of election used in the primaries: majority voting.”

As it happened, a recent (March 2016), Pew research poll did just that. Using that data, the French mathematicians found that Kasich and Sanders came out first and second, Ted Cruz landed in the middle, followed by Clinton. Trump was dead last. Does this mean that the new, improved polls say Trump would lose to Clinton with our method of voting? No. In a hypothetical head to head between them, the French mathematicians show that it would be possible for Trump to win with the majority vote even though the electorate prefers Clinton.

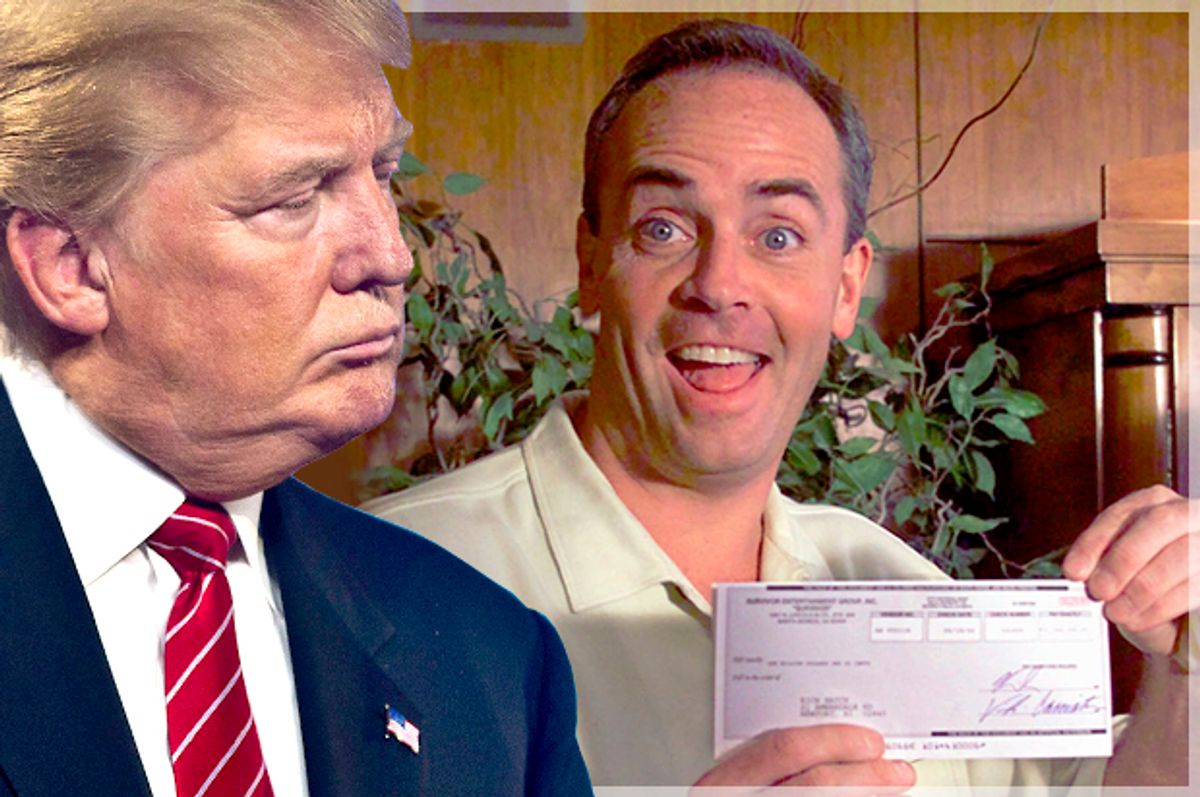

How can a man that so many think would be a “terrible” president hypothetically end up besting Hillary? Although NBC's reality TV chief credited Trump's own show "The Apprentice" this week with making him a viable candidate, the answer can really be found an earlier show — "Survivor."

The answer can be found in “Survivor."

The first season of “Survivor” debuted in 2000. Measured in Internet Time, that’s ancient history. A very long time ago. An origin story. The basic set up was simple: a gender-balanced group of sixteen American adults were required to find their own food, water, and shelter on a lush tropical island. Insofar as straight survival cannot be made into a game (not yet, anyways—or, rather, not on purpose), the genius twist was to half-fake the “survival” part and make the game about politicking. Every three days, players voted one person off the island. The game created dramatic tension by rewarding challenge winners with temporary immunity from the vote, but it became riveting entertainment when players started behaving badly.

They formed alliances. --Was that cheating? Richard Hatch stripped off his clothes. --Was that fair? Hatch was one of the first great villains of reality television, loathed by viewers and fellow game players alike. He was charismatic, belligerent, irascible, and naked. And he didn’t care that his flagrant state of undress might offend his fellow castaways. When producers didn’t insist that he cover up, he knew that they knew that viewers would be mesmerized by the sight of his blurred-out junk.

From the outset, Hatch understood that he was playing a game, a game that existed because it was a show, and that the show’s survival depended on how much money it made for the network. The viewers who mattered weren’t on the island but sitting comfortably at home, eating snacks and watching commercials. Well educated, comparatively wealthy, and armed with a background in corporate, he was the first to come up with the idea of forming an alliance, then persuaded his fellow oldsters to form a solid voting block that easily knocked off the youngsters. Once they were all gone, the tribes reformed, and Hatch starting picking off his tribemates, one by one.

Based on the model of majority voting, the final round came down to Richard Hatch and Kelly Wiglesworth. It was up to a woman to decide the winner. Would Sue Hawk support the man whom everyone despised, or would she vote for the woman who was almost—but not quite--as hated by the other players on the island? Here was Sue Hawk’s famous justification for her choice:

This island is full of, pretty much, only two things: snakes and rats. And in the end of Mother Nature, we have Richard the snake, who knowingly went after prey; and Kelly, who turned into the rat that ran around like rats do on this island, trying to run from the snake. I believe we owe it to the island spirits we have come to know to let it end in the way that Mother Nature intended: For the snake to eat the rat.

Her logic, then, was that the worst person deserved to win because he was more authentic to his true self, even if that self was an asshole.

Hawk genuinely loathed Hatch, yet the then-president of CBS, Les Moonves, speculated that his willingness to be the bad guy was exactly why he won. “The bad guys are often the most compelling characters,” Moonves said. “And people at home may have seen that and recognized what happens in their own lives, in corporate society or whatever. They have been thinking: ‘That’s why I haven’t succeeded. The bad guys are to blame.’” For that same reason, one might expect cathartic comeuppance with Hawk serving her revenge cold at the end. But no. By being an unrepentant jerk, Hatch turned himself into an evil godfather bestowing the curse/gift of fame on the entire cast. Hawk couldn’t have known what a monster hit the show would become, but she acknowledged that he’d made the game in his image, and closed the loop by declaring him the winner.

Hatch’s villainy not only made “Survivor” into must-see TV but set it up to become one of the most enduring—and profitable—series for the network. That summer, the show raked in money for CBS. If the network’s tacit approval of Hatch’s vulgar tactics sounds familiar, it’s because Moonves, who’d been promoted to executive chairman and CEO in the meantime, recently made similar remarks regarding Trump’s positive effect on his network’s coffers. “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” he said of the 2016 presidential race. “Man, who would have expected the ride we’re all having right now? ... The money’s rolling in and this is fun. I’ve never seen anything like this, and this going to be a very good year for us. Sorry. It’s a terrible thing to say. But, bring it on, Donald. Keep going.”

By going naked on network TV, Hatch exposed America’s cultural underwear. It may seem as if backstabbing and brinksmanship and humiliating yourself for peanut butter are necessary concessions to the terms imposed by the game. As “The Hunger Games” later underscored, the artificial parameters of “Survivor” presented competitors with one unswerving goal: to survive the machinations of the other players. (Non-American versions of “Survivor” might have two winners, and often did.) Surviving “nature” was incidental, because there was no profit in killing the castaways. Just get them off the island and out of the game, maybe crush a few dreams for good measure along the way.

But watch the first season of the French edition of “Survivor,” re-titled “Koh-Lanta.” The essential features of the game were the same: a bunch of high-conflict strangers on a deserted island voted off players, using immunity challenges put into place by the producers to prevent pure (boring) competency from taking over. But the French players reacted totally differently to the set-up. They were thoughtful, cooperative, and pretty good at sharing. They agonized each time they had to eliminate one of the group, quoting Great Philosophers to soothe their wounded souls. The man who won did so because the others couldn’t bear to let him go. So helpful. So kind. So caring. In short, he was beloved. Their mutual respect for each other was genuinely startling. France is a socialist country, you know. They value cooperation. (Cue the German invasion jokes here).

By contrast, Richard Hatch went to jail for tax fraud, his fellow castaways still refuse to speak to him, and one of the female players sued the producer, Mark Burnett, alleging that he had arranged for her to be voted off the island, thereby directly manipulating the outcome. The lawsuit was settled out of court.

***

Reality shows are staged events, but this is true of all television, including the news. It is a matter of degrees, not of kind. Over the past two decades, political theater has morphed into political entertainment. What used to be a ceremonial matter of state is now a 24/7 carnival designed to push emotional buttons and exploit our love of spectacle. “This is not entertainment. This is not a reality show. This is a contest for the presidency of the United States,” Barack Obama said earlier this week when asked about Donald Trump. What President Obama should have said is that it’s not supposed to be entertainment. It’s not supposed to be a reality show. But wishing doesn’t change the fact of what it has become.

Last century, back in 1999, the Neiman Institute at Harvard University published a report regarding the impact on news when the networks shifted to a for-profit model. The most immediate change was a content shift away from hard news. In its place: gossipy coverage of current events so patently unserious that that “even a casual viewer can see that they are not governed by news values in the traditional sense.” Though sometimes potentially in depth, the stories were not prepared by “the kind of journalist whose job it is to provide citizens with information they need to participate in a democracy.” When news is built on getting ratings, the report noted, it discourages intellectual debate in favor of profitable sensationalism.

Two decades later, the United States is an oligarchy, governed by economic elites, and hardly anyone remembers what serious "news values" used to be. No longer is any televised media conglomerate trying to produce hard journalism, instead feeding us simulations mimicking the aesthetic conventions of earnestness. The rise of the internet accelerated a trivializing trend that was already blurring the boundaries between reality and its representations. Right now on Facebook, the first successful penis implant is trending. So is the fact that singer Sinéad O’Connor was found. I didn’t even have time to hear she’d gone missing. Though these distractions pique curiosity, none of it helps voters grapple with economic inequality, crumbling infrastructures, climate change, social injustice, or any number of large, complex and global problems that require a functioning government to address. Public discourse has devolved to the point that consensus is unintelligible to the masses, making it easier for corporations to keep profiting from the ignorance they created.

Enter Trump, the only candidate that’s been the star of his own long-running reality television show, “The Apprentice,” meaning he understands better than most how the media shapes perception. The candidate that wins the presidency has long been the one most adept at the latest form of mass media, from radio, to television, to Twitter. Disdaining Trump for being a reality TV star is no different than sneering retrospectively at Ronald Reagan for having been a B-list Hollywood actor, and just as politically in effective. That Trump immediately grasped that reality TV was no fluke suggests he is playing a very long game. But it’s his background as a pro-wrestling impresario that reveals why it’s so bafflingly difficult to stop him.

Judd Legum connected the breadcrumbs when he excavated an essay by philosopher Roland Barthes, a French semiotician mesmerized by the American capitalist landscape. In “Mythologies,” 1957, Barthes had contrasted American pro wrestling to boxing:

This public knows very well the distinction between wrestling and boxing; it knows that boxing is a Jansenist sport, based on a demonstration of excellence. One can bet on the outcome of a boxing-match: with wrestling, it would make no sense. A boxing-match is a story which is constructed before the eyes of the spectator; in wrestling, on the contrary, it is each moment which is intelligible, not the passage of time… The logical conclusion of the contest does not interest the wrestling-fan, while on the contrary a boxing-match always implies a science of the future. In other words, wrestling is a sum of spectacles, of which no single one is a function: each moment imposes the total knowledge of a passion which rises erect and alone, without ever extending to the crowning moment of a result.

“In the current campaign,” Legum explains, “Trump is behaving like a professional wrestler while Trump’s opponents are conducting the race like a boxing match. As the rest of the field measures up their next jab, Trump decks them over the head with a metal chair.”

Quaintly, boxing matches can be fixed. But when outcomes are rigged, the reasons why are clear—someone placed a bet they couldn’t afford to lose--and Lord Queensbury's 19th-century rules governing good sportsmanship still remain firm. Whereas it’s absurd to accuse a professional wrestling match of being faked, for they invert the classed structure of spectacle itself, letting the audience see its cheerfully crass desires mirrored in the simulated vulgarity of the action. Who would fault Sylvester Stallone for not being Rocky Balboa, even though it is his job to convince us that he is? Note that the inability to separate the character (“Rocky”) from the actor playing him (“Stallone”) is the very definition of delusion, helping to explain why Trumpers believe that liberals are insane. Why, it’s as if lefties don’t understand that Trump is playing the impresario inside a corrupt political system built on empty promises and falsehoods!

If all of it is staged, then why bother? Why would anyone watch fake brawls if the outcomes are known? Well, why does anyone seek to be entertained? Fatalistic institutional distrust permeates every level of society, leaving only bloodlust precisely because it claims real bodies to share the pain, turned into scapegoats to take the blame.Unlike the passivity of staring at screens, arena events enfold the spectators into the spectacle. The authenticity of the action does not matter, as long as it allows those present to revel in the collective ecstasy of apotheosis.

According to mythologist Joseph Campbell, apotheosis is a state of expanded consciousness experienced by the hero after defeating his foe.

To his followers, the hero is Trump, a rich man getting into the ring with them instead of walling himself off in castles and snooting down his nose. To the disenfranchised, he offers the vicarious thrill of victory every time he trounces another opponent, or promises to suppress another supposed enemy—Muslims, Mexicans, the Chinese, etc.--who are legion, faceless, and always changing. In his supporters' minds, racism or religious intolerance has nothing overtly to do with his sweeping condemnations of entire groups of people who do not look like "Americans" to them. It is a simple (if unexamined) paradigm of good vs. evil, forged by Thor's hammer on the anvil of the Avengers, as seen most recently in "Captain America: Civil War." And it is all just talk, anyways. Just a show, as seen on TV, the friendly, comparatively CGI-free land from whence Trump hails.

But when all the world’s a stage for reality TV, TV is all we see. And if the emperor has no clothes? Nobody cares anymore. It's how the first guy won his show.

Shares