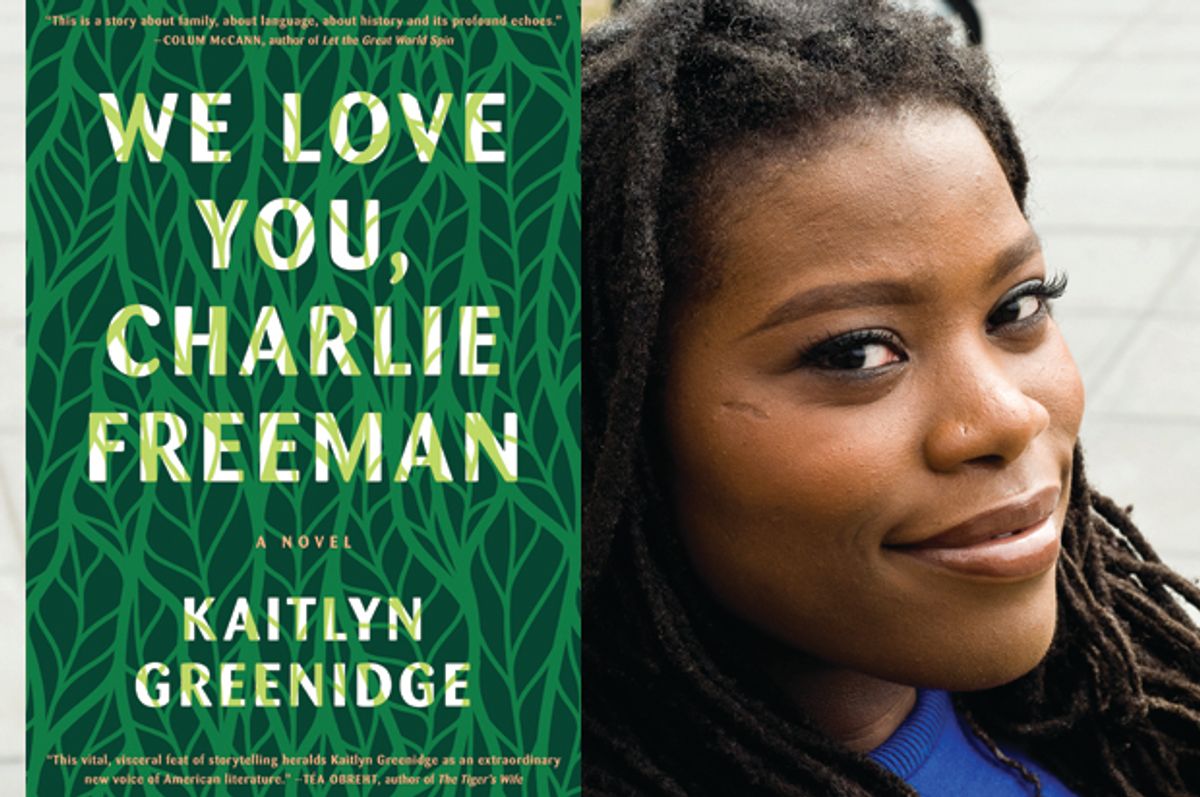

Whenever I meet someone for the first time, I sometimes imagine what their parents must be like: the features of their face, the force of their personality. I think about the million micro-pressures exerted day after day by siblings and aunts and uncles, a vast network of love and guilt and expectation--all of it printing into the amalgam in front of me. Kaitlyn Greenidge's debut novel, "We Love You, Charlie Freeman" captures that same fullness of family -- its blemishes, its cracks, the tiny betrayals and the ties that bind.

Full disclosure: Kaitlyn and I have been friends since graduate school. We've spent many hours, cackling together in the corners of dark bars. From the start, her writing has been easy to fall in love with: simple, elegant, and possessing an immense tensile strength. Under a clumsier author, the story of a black New England family moving to the Berkshires to teach sign language to a chimp might read like a setup to a hateful joke, but in Greenidge's hand, she reveals a profound understanding that the things that damn us may also save us.

Each family member feels so distinct and yet completely a part of each other. Whats your approach to writing families in fiction?

I wanted to write about a family that fundamentally can't communicate with each other. There is a disconnect. I was just at a book club yesterday and someone said something like, "So many problems would be solved in this book if a family member just asked more questions." They seemed surprised that this did not happen, but I think that's probably more common in families than not--you don't really want to know more about your family members, sometimes, because it is too painful or it brings up your own stuff. So you don't ask. You go do something else, or you do something that at the time doesn't make sense but you realize is really just your body trying to force the questions your conscious mind could not.

The book gives the story to Charlotte, the eldest. Why her as opposed to Callie or their mother Laurel for example?

I actually think the book is about Callie, the 9-year-old sister. Charlotte is the dominant voice, but Callie is, arguably, the daughter that survives. I liked writing in Charlotte's voice, the voice of a teenaged girl--such a disparaged figure, especially in literary fiction. I liked forcing readers to take her emotions and observations seriously. But the book belongs to Callie.

How does Callie survive?

She stays emotionally open to something. It's not clear what--I still don't know what. I don't want to give too much away but Callie can imagine a future in the way that the rest of the family maybe can't.

Is that a virtue?

It is incredibly hard, incredibly wounding to stay open emotionally. It's why very few people make it to adulthood truly doing so. I mean, really, really open: not just in moments when it serves you well or when you can already guess the outcome. I know very few adults who are able to live like that--probably only two or three.

I read Callie as a character that drifts in and out of delusion. But. We have this tendency in our culture to distrust emotional honesty and especially to distrust optimism. We make the assumption that the cynic is the truth-teller, telling us all the things we are too scared to face. Sometimes that is true, but not nearly as often as people think.

Cynicism is a very, very easy out. And it does not contain any greater truth than optimism does. Not really. There are many reasons, in this particular historic moment, why cynicism is touted as some great truth serum. But ultimately, that viewpoint is false and destructive. There's nothing "realer" about pessimism. It is not a better lens for viewing the world.

Near the end of the book, Charles talks about wanting to talk about his love for something. This was a particularly poignant moment for me — to resist cynicism or hopelessness with a stubborn love. Can you talk more about that choice for this character?

I didn't know how to write men. Or, I was intimidated writing a male character who was not a jerk or completely useless. All the other men in the book are straight-up emotional predators. I wanted to try to write a male character who did not operate from that place. Charles began to make sense to me when I realized he was a character who, as you put it, "resists cynicism or hopelessness with stubborn love."

One of the repeating thematic ideas in the book is self-restraint. Nymphadora's restraint as a Star, Charlotte's restraint in, among other things, keeping her mother's secret. Charles' restraint when he's teaching the school. What role does self-restraint play in your characters' lives, and how they practice family, friendship, or race?

There is a feeling, when you are in a marginalized position, that if you just act really, really good and nice, the dominant group won't hurt you. And acting good and nice is dependent upon how the dominant group defines those terms. That's very real: it can ensure you don't get killed sometimes. But only sometimes.

At a certain point, there's no amount of respectable behavior you can engage in — the dominant group still views you as a little (or often more than a little) less than human. And the internal toll of constantly moderating your behavior like that — I wanted to explore that. When you are not allowed to publicly express yourself, and you police yourself to make sure you do not display the full human concert of emotions...what does that do to your internal life?

What does it do to your internal life?

From my experience? It screws with your emotional reactions to everything. It can seep into your intimate relationships, if you aren't careful. You lose the ability to emotionally react in a natural way, or you are constantly second guessing your reactions, or your reactions can only be expressed in one tone — sadness, or anger or passive aggression. You cannot have authentic emotional interactions after a bit. Or, it becomes significantly harder.

Callie's turn toward magic is an interesting one, especially given the hard scientific influences that surround her living in the institute. How does her use of mysticism and magic define her role within the book and in her family?

Callie is the only family member who stays emotionally open. She has a willingness to believe in good. I wanted to explore that belief. She's not old enough to be self-conscious about it or to think of it as a detriment yet. I wanted her to have a space that let her push a belief in good to an extreme and a desire to dabble with the metaphysical and the supernatural seemed like a good place.

Does being the youngest play a role in that? In what ways do your characters' roles in the family influence the person they become?

Oh, the birth order question. I don't know how much that plays into it. I wanted a character who was optimistic, who would stay optimistic despite the evidence, and see what mental gymnastics that character engages in to do that.

You're one of three sisters. How do you think that's informed the way you see things?

There are always three versions of an event. It has been that way all my life: there is the thing that happened, and then everyone's interpretation of it. My family exists in an unending re-enactment of "Rashomon."

It used to drive me crazy when I was a kid: particularly because my sisters, not much older than I, insisted on their version being the truth. I'm old now. Now, no one in my family is so silly as to believe their version contains the whole truth. But there are still those moments when we will be talking about something and the conversation will run aground. It really does feel like that, like the bottom of a swift canoe suddenly scraping against a sandy river bottom. And we will have to stop and say "I remember that this way." "Well, no, I remember that this way." "Well, I don't remember that at all. That wasn't even on my radar. What I cared about then was this."

It's incredibly frustrating but I'm glad I grew up that way. It's given me a healthy skepticism of dominant narratives, of anyone trying to say "My story is the only possible truth."

How do you view fiction in connection with history?

I love both. Fiction, though, allows for imagination on the part of the reader. It is not didactic. It lets the reader form their own conclusions. It hopefully is not trying to convince you of anything. It's magic. History is trying to convince.

Convince us of what?

History is trying to convince the reader of a certain version of events. Fiction, good fiction, leaves events up to interpretation. Most history is in the service of something other than itself: a nation, or a despot or the suppositions, prejudices and biases of the author. Fiction is also in the service of its author, but it only works if it seduces the reader into believing that the text is up to interpretation, that the reader is drawing her own conclusions, and that there is a certain mystery when you close the book. It's that James Baldwin quote: "The purpose of art is to lay bare the questions that have been hidden by the answers."

In graduate school, you talked about wanting to write the book that you yourself would want to find and read at the library. Have you done that? What does it mean to you to have done that?

Yeah, that's a Toni Morrison quote. I mean, as I wrote the book, on the days that I was more optimistic, I though "I can't wait till it exists and I can read it." A 13-year-old just tweeted at me that she got this book for her birthday and that honestly makes me so, so excited. It's not like I am home right now, reading this book at my leisure. But I'm excited that it is out in the world.

So what's the book that doesn't exist yet, but needs to?

So many books. A book about what it is like to be educated in our current broken system. A book about what it's like to grow up poor in an African country that's being colonized by China. A book about what it's like to watch our world literally melt away while nobody cares. And about existences I don't even know about yet because I don't know to know about them. I don't understand this desire to only read about people who are like oneself. That makes no sense to me. Why open a book? Or only to read books where you feel inspired by the characters or want to be their friends. I don't get that, either. That's what is so lovely about fiction: unlike movies, anyone can be a protagonist. Movies: maybe one out of a thousand will have someone other than a middle-class, reasonably attractive white person in their twenties as the hero. Books, it can be anyone.

Shares