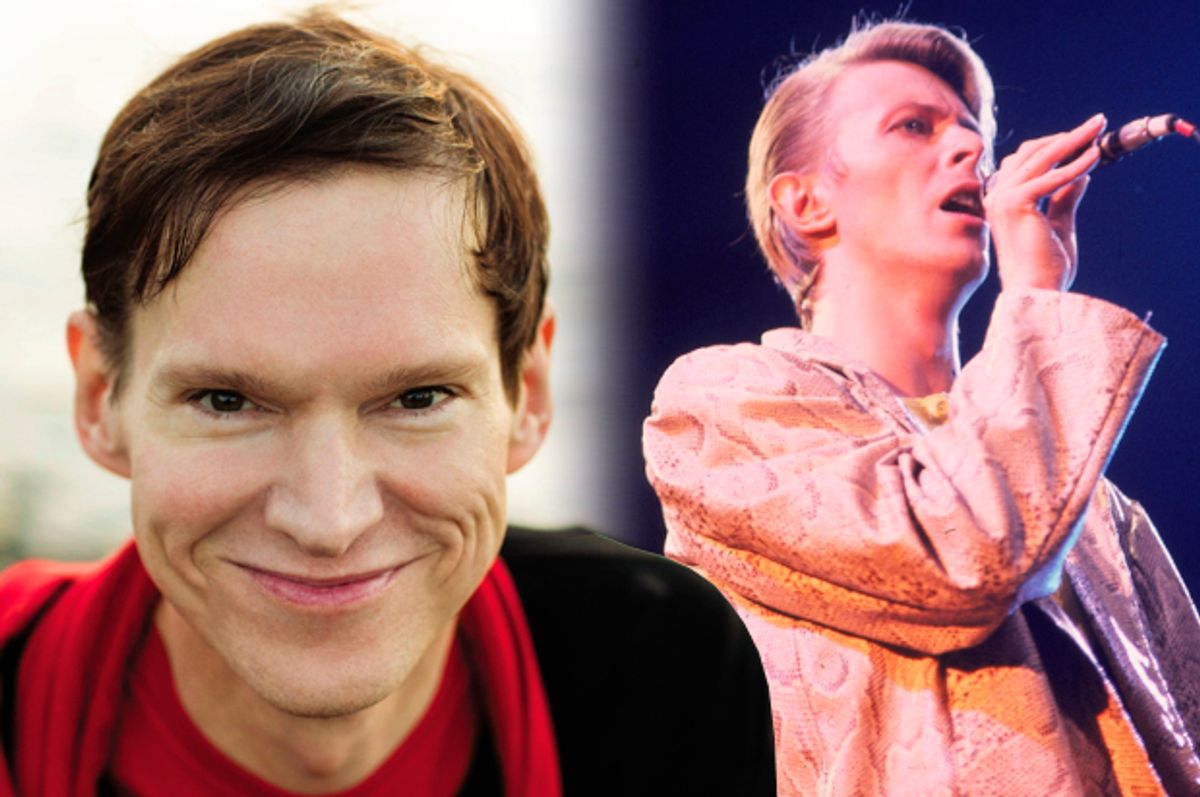

When Rob Sheffield learned that David Bowie died, he stayed up all night and the next day writing about his hero. The longtime critic and “Rolling Stone” columnist wrote with no real purpose or goal in mind, but simply tried to get ideas on paper. It was his own personal wake for the man who wrote “Space Oddity” and “Starman,” who embodied so many different roles, who inspired Sheffield and millions of other fans around the world. “Words were just pouring out of me,” he recalls. “It was impossible not to write about David Bowie and listen to David Bowie and mourn for David Bowie.”

In the morning, as others were just waking up to the sad news, Sheffield received a call from his editor, who wanted him to keep writing. He spent all of January 2016 and part of February reconsidering Bowie’s greatest hits and his greatest guises, and the result is “On Bowie,” a book-length eulogy for the mercurial rock star that debuts today. Sheffield takes us through the man’s life and career, from his first fluke hit through his glam ascendancy, from his forays into Philly soul to his Thin White Duke experimentalism, from his early ‘80s highs to his late ‘80s lows, from his disappearance in the 2000s to his comeback in the 2010s.

Bowie, of course, is one of the popular and written-about rock stars in the world, and there are scores of biographies that trace a similar trajectory. What makes “On Bowie” unique—what makes it something other than redundant—is its mix of biography and autobiography. In writing about Bowie’s career, Sheffield cannot help but write about his own life and his own experiences with Bowie’s music. As a teenager growing up in Boston, he found inspiration and consolation in songs like “Heroes” and “Let’s Dance” and “Boys Keep Swinging,” dissecting their lyrics and sequencing them on countless mixtapes for himself and his friends. This kind of close identification with an artist can be indulgent or critically irresponsible, but in “On Bowie,” it’s absolutely crucial in presenting the celebrity through the eyes of a fan and in humanizing an artist who barely appeared human onstage.

This is perhaps Sheffield’s greatest trait as a critic: He writes with the enthusiasm of a true fan, whether he’s extolling A Flock of Seagulls in the “Spin Record Guide” or explaining how music helped him grieve his wife in “Love Is a Mixtape” or examining the impact New Wave had on his life in “Talking to Girls About Duran Duran.” His prose burbles with joy and excitement, which may cloud his judgment (he perhaps overpraises Bowie’s ‘90s output) but makes his books refreshing and relatable. Anyone who has ever carefully planned out a mixtape or listened to the same song ten times in a row or driven hundreds of miles just to a see a band perform will recognize something of themselves in Sheffield’s writing—just as Sheffield recognized something of himself in David Bowie.

Especially after so many quick eulogies and hot takes, the topic of David Bowie still seems inexhaustible. Why do you think that is?

David Bowie is somebody who exists on so many different planes. Every audience has their own David Bowie and every culture and really every fan has their own David Bowie. For me, part of grieving for David Bowie after his death was having so many conversations with my friends about our experiences with him and learning all the different things he meant to people. There are so many different ways to live your Bowie-ness and so many different ways to hear him. It’s funny that is was only after he died that I found out what a huge deal “Labyrinth” is in his canon. When that movie came out, I was already a teenager and was not interested in seeing David Bowie in a kids movie with Muppets, so I didn’t realize that for a huge number of his younger fans “Labyrinth” is the gateway drug that got them into Bowie. That’s an example of the things that I kept learning about David Bowie, who is someone I’ve loved all my life and someone I keep learning more and more about even after he died.

I’m constantly surprised by the love for “Labyrinth.” It definitely seems to be a movie that millennials have embraced.

There was a beautiful tribute at a punk DIY spot in Brooklyn called Silent Barn, where a bunch of bands covered the “Labyrinth” soundtrack all the way through. There were ten bands, and each one would play a different song. That was one of the strangest David Bowie tributes I witnessed, but it was a beautiful thing. It was this different side of David Bowie for people who were born in the ‘80s or ‘90s. For me, though, I barely remember that this movie ever happened. I was a New Wave kid in the ‘80s, so the David Bowie of “Let’s Dance” was huge for me. For a lot of other fans, though, that album is some aberration in his career, where he tried to do something that didn’t hold up very well in retrospect. I’m very much a “Let’s Dance” loyalist, and another thing I took away from the conversations I had with friends about David Bowie was that I was maybe in the minority about that. His New Wave period didn’t mean the same to everybody that it meant to me.

My first Bowie record was “Never Let Me Down,” so I have a weird affection for that era.

You’re definitely in the minority there.

No kidding. But it was the first record he released when I was of record-buying age. You have a completely different experience with Bowie depending on where you enter his story.

For me it was “Lodger.” That was the first one that came out when I was already a David Bowie fan. I had already been listening to FM rock radio and knew “Heroes,” and then “Lodger” came out. I have a massive affection for that one. I’m capable of very long and very tedious arguments in bars defending that record. I love “Lodger.” You can love David Bowie in all these different ways, so there’s always more to discover from him. My theater friends have a totally different Bowie than I do. My fashion friends have a completely different Bowie. My art friends, my film friends, everybody. He dabbled in so many different kinds of stuff and incorporated so many different types of expression into his overall statement, and it’s amazing that people live and die for entire corners of the Bowie universe that I barely even know. Part of the way he saw his journey as an artist was dabbling in everything that interested him, whether he had a deep-rooted talent for it or not. He figured he would do it and if it came out disastrously, he’d have a laugh at it and move on. That meant he was able to participate in so many different worlds and so many different artistic languages.

The book portrays him as a fan in his own right, someone who’s constantly listening to other artists and integrating their ideas into his own music. Sometimes he has great taste, as with Iggy Pop or Lou Reed. Sometimes not, as with the Polyphonic Spree.

It’s amazing and really inspiring how personal a fan he was. That’s something that he never lost even after he had been making music for fifty years. That last album he made—when he knew he was close to the end of his life—was so influenced by Kendrick Lamar and D’Angelo, artists who were so much younger than he was. But he listened to them and got different ideas about how to approach music. He was still so passionate about learning and absorbing new influences. There’s an awful lot of rock stars his age who do not share that trait.

It never sounded like he was retreating into the music of his own adolescence or trying to recapture an older sound. He didn’t seem like he was interested in looking backwards.

That’s a constant throughout his career: He’s always interested in the moment. David Bowie was less interested in nostalgia than any great rock-and-roll artist who ever existed, whether it’s 1965 and he’s doing John Lee Hooker and James Brown songs or it’s 1975 and he’s influenced by the O’Jays and the Stylistics or it’s 2015 and he’s listening to Kendrick and D’Angelo. He’s always interested in what’s going on right now. It’s really weird to think that he was listening to “Black Messiah” and “To Pimp a Butterfly” at the same time we were all listening to those album and getting our minds blown by them. And David Bowie was also getting his mind blown by them. He was willing to learn from it. He was someone who was never satisfied with anything he did before and really reluctant to rest on his laurels. He was definitely not someone who was willing to settle for “legacy artist” status. He always wanted to do something new.

But he’s not always successful. “Blackstar” is amazing, but there were times when he was listening to something but not able to transform it into something that’s new or personal. I’m thinking of “Earthling” in particular, which tried to incorporate some drum ‘n bass elements.

Sometimes he’d try something and it would get the better of him. When he tried to do a reggae song [“Don’t Look Down,” off 1984’s universally-reviled “Tonight”], to his credit he only tried to do one reggae song. He did that one and was like, okay, reggae requires a certain emotional skill set and a certain rhythmic skill set that I do not have. He didn’t make a lot more reggae songs. He tried it once and it didn’t fit his particular toolbox. It’s funny you mention his drum ‘n bass album, which is a good example of him hopping a trend right at the time everybody else is really done with it. So the production was not impressive, but he still managed to write songs that were really impressive. He wasn’t necessarily trying to become a master at any of these styles, but just wanted to see what he could learn from them.

Have you ever read the speech he gave at the Berklee College of Music for its commencement in 1999? It’s a really beautiful and funny speech. He said it was funny to be a songwriter talking to real musicians. He said he figured out his place in music in the ‘60s when he tried playing saxophone. And he was a terrible saxophone player and knew he couldn’t express himself playing that instrument. But he also said something like, I can put together different elements of different music and I had figured out the Englishman’s true place in rock and roll. Which is that there was no way he was going to approach anything from the context of virtuosity or authenticity. All he really had to bring to it was curiosity.

That attitude does so much to humanize him. Here’s a guy playing with all these masks and disguises, yet there does seem to be a curiosity driving every decision.

There’s a continuity through all the different phases. He’s a very musically curious and emotionally curious and sexually curious and artistically curious human presence through it all. There’s a tangible emotional aspect to all these experiments that he does. Some of them turn out to be disasters and some of them turned out to be hugely influential. But he was constantly willing to try things and see what happened.

And part of that was constantly referring back to himself and creating this personal mythology through these various songs. He spent decades exploring that outer space metaphor he introduced on “Space Oddity.”

There’s this great song on “Heathen” from 2002 called “Slip Away,” and it’s about being in Coney Island and riding the ferris wheel with his daughter. At the top of the ferris wheel he looks down and it feels like he’s looking down on his past and all these outer space adventures that he used to contextualize in whatever drug or sex or rock-and-roll extreme he was indulging at that time. There’s this beautiful line in the song where he sings, “Down in space it’s always 1982.” It cracks me up to think that this theme of space exploration is something he started strictly as a gimmick, but it became a lifelong metaphor for self-discovery and transformation. Part of what makes him such an inspiring figure is that he was committed to that transformation his entire life. How insane is it that he was able to actually have a happy marriage for the last couple decades of his life—and with a model! That seems like the ultimate transformation.

And it meant he was able to age with some dignity, as opposed to having to go back and play “Starman” on nostalgia tours. He’s one of those rare artists for whom the narrative didn’t stop. His story kept going as he kept evolving.

Absolutely. He was not willing to concede that the narrative had stopped, and I think he attracted the type of audience that didn’t want him to stop. Nobody wanted to go to a David Bowie show and hear all of his greatest hits from the early ‘70s. That would not have been satisfying. He attracted the kind of audience that wanted him to keep trying new things, whether he was good at them or not. I remember seeing him at Madison Square Garden in 2003 where he did three songs from the album “…Outside.” It’s a terrible album, but he did three of those songs. At one point, he said, I’d like to do another song from “… Outside,” and there were a few assorted whoo’s. And he said, All seventeen people who bought that album are clearly here in this room.

We knew we could trust him to do what seemed interesting to him at the moment. We knew he wasn’t phoning it in. If you went to a David Bowie where it felt like he was trying to give the audience what they wanted, it would have been exactly what the audience didn’t want. He wanted his fans to feel hideously appalled and sometimes feel pity and sometimes feel shock and sometimes feel anger. He wanted that response from his fans and that’s what he got.

One of the things I’ve appreciated about your books is how you write with the enthusiasm of an unabashed fan. This book and especially “Talking to Girls About Duran Duran” are about what it means to be a fan and have such an intense connection with an artist. Is that draws you to David Bowie, who shares that similar sense of fandom?

When I was a kid, that was something that was easy to notice right away. He was a fan of the music around him, and he was someone who didn’t see it as a thing where artists were on this mountaintop and the audience was on the ground accepting whatever thunderbolts were thrown down from the clouds. He was someone who was very engaged with his audience. You remember that greatest hits album, “Changesonebowie,” that came out in ’76? I love that album. It’s a greatest hits album where every song sounds like a different guy who’s a fan of something completely different. Listen to a song like “Diamond Dogs” and it’s a guy saying, My god, the Stones are the best ever! Then you listen to “Fame,” and it’s a guy saying, The O’Jays are where it’s at! You listen to “Golden Years,” and this guy is saying, Disco is a galactic language of communication and language! Then you go back to the first side and listen to “Space Oddity,” and that guy is strumming an acoustic guitar and saying, Bob Dylan taught me so much!

That’s one thing about David Bowie: H e was always upfront about being a fan in a way that was radical and unprecedented for rock stars in the ‘70s. He was very upfront about the fact that he was stealing ideas from everything he liked. In the book I talk about that interview with Dinah Shore on her morning talk show in 1976, where he says, I’m very flirty and very faddy and I get easily saturated by things. I’m a big fan of different artists and I just steal things from them. And Dinah Shore basically says, I can’t believe you’re admitting this on TV. His response was, I steal things. That’s what I do. That’s what it really means to be a fan. We steal pieces of our emotional selves from the music we love. There are aspects of my personality that I have modeled on Bowie and aspects that I based on Aretha Franklin and aspects that I modeled on Janet Jackson and Stevie Wonder and Paul McCartney and Lou Reed—all these different artists who have been so inspiring to me in different ways. That’s the thing about being a fan: You steal things from the artists you love. David Bowie saw that as a lifelong heroic, romantic quest, and he was not at all embarrassed about that aspect of being a fan. To me that’s very moving and inspiring. What I love most about David Bowie is that he celebrated the romance of being a fan.

And that elevates the fan. It allows you to create your own personal Ziggy Stardust out of all of these different people. Listening becomes a creative endeavor rather than something passive.

You don’t just listen to one kind of music and become one kind of persona. You listen to different kinds of music and explore different kinds of art and read different kinds of books and then you combine those ideas in ways that turn out to be who you are. That can be a threatening idea, especially for rock stars in the ‘70s who were more interested in establishing their roots or their authenticity. Whereas David Bowie presented being a fan as a creative adventure. It’s not about being a passive receptacle of pop culture. It’s more about being a creative participant in pop culture. As long as you’re passionate about music, something creative will come of it.

Shares