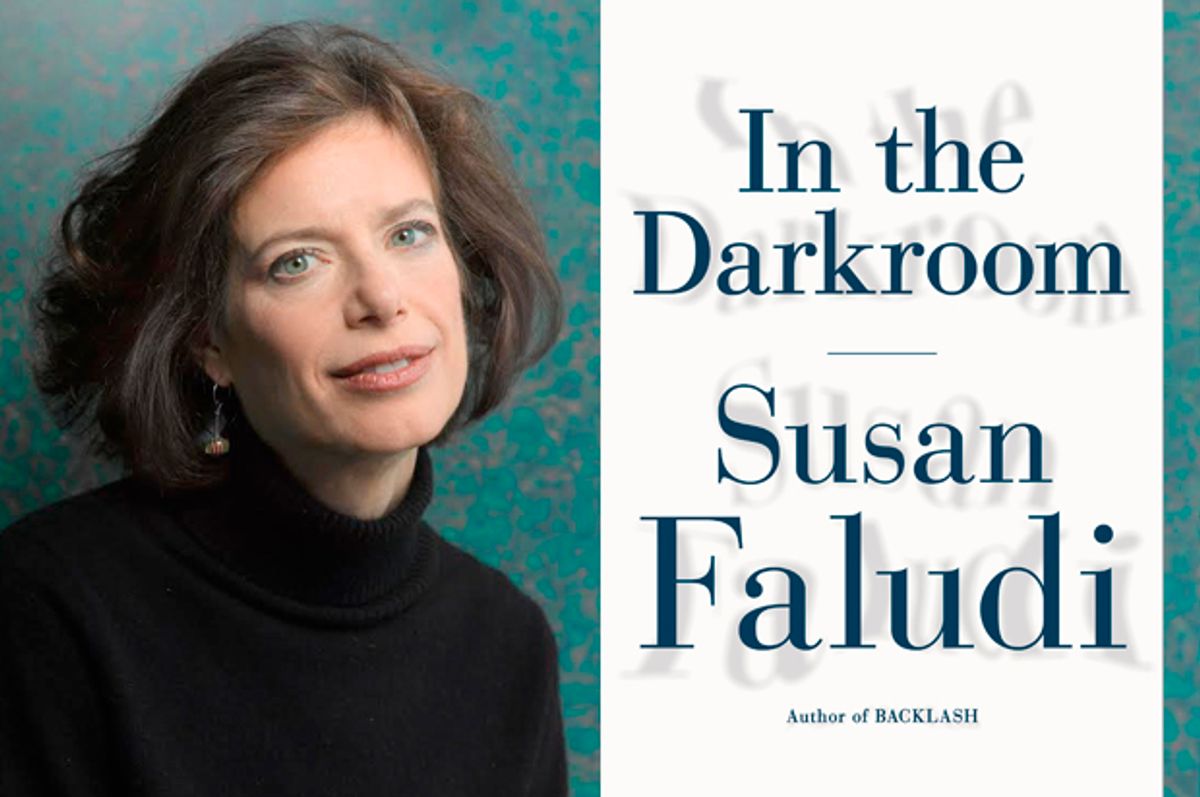

In her compelling new book “In the Darkroom”, bestselling feminist writer Susan Faludi turns her critical eye from deconstructing gender myths inward, to her own life. The catalyst? Her estranged father, who, at the age of 76, sends her an email with the subject line “Changes.” Her father announces he has “had enough of impersonating a macho aggressive man that [she has] never been inside,” and is now a woman. “Love from your parent, Stefánie.”

“I devoted my life to studying gender issues, and then the question of the age—on gender—shows up in my own backyard,” Faludi said in a phone interview with Salon. “I felt that I couldn’t move forward honestly and engag[e] with questions of gender without admitting to my own experience—on some level [not doing so] would be dishonest.”

“In the Darkroom” encapsulates the approximately ten-year period that Faludi was able to get to know not just Stefánie but her father before her father’s death in 2015. In that decade of email correspondence and frequent visits in Stefánie’s native Hungary, we witness the dance between Faludi and Stefánie as they build their relationship—in the culminating pages, a literal dance, as Susan twirls her to the music of Michael Jackson at a trans party on the outskirts of Budapest. Susan, the intrepid feminist journalist who gently but persistently questions her father about his/her life—first as István Friedman, the Jewish boy growing up in Nazi-occupied Budapest, then as Steven Faludi, the violent and sometimes abusive father, and then as Stefánie Faludi, the trickster and coquettish feminine woman.

The acclaimed feminist, who has spent a lifetime fighting sexism and eviscerating gender myths, finds herself confronted by a woman who revels in gender stereotypes. “‘You write about the disadvantages of being a woman, but I’ve only found advantages,’” she tells Susan very matter-of-factly. “‘Men have to help me. I don’t lift a finger. . . It’s one of the great advantages of being a woman.’” On another visit, Stefánie gleefully says, “It’s great being a woman... I look helpless, and everyone helps me. It’s a racket. Women get away with murder!” And, on another, she berates Susan for not having children: “This business of no children,’ she said. ‘It’s not normal.... Without children, your existence has no meaning.... Your books will stop selling. People will forget all about what you wrote.’”

Ironically, Stefánie repeatedly tells her daughter to write a book about her but is less than forthcoming with details. Information is piecemeal—not necessarily because Stefánie is ashamed of her past, but because parts of the past carry deep, traumatic wounds. Wounds born from living through the Holocaust, wounds born from the pressures of conforming to mid-century notions of American masculinity. “‘Women didn’t approve of me,’” Stefánie confesses to Susan. “‘I didn’t know how to fight and get dirty. I’m not muscular, I’m not athletic, I had a miserable life as a man.’”

Their reunion, shortly after that 2004 email, is at first extremely awkward. For Stefánie, her process of becoming a woman depended upon gender stereotypes; for Susan, her process of becoming a woman—and especially a feminist—depended upon her shattering those stereotypes. Bickering over gender essentialism betrays the book’s humor — sometimes disconcerting, sometimes dark.

The repeated bandying of the word “normal,” for example, conveys the tension between father and daughter. When Susan first visits her father, Stefánie asks her to leave her bedroom door open at night, after noticing Susan has been keeping the bedroom door shut. “Why?,” Susan inquires. “‘Because I want to be treated as a woman,’” Stefánie responds. “‘I want to be able to walk around without clothes and for you to treat it normally.’”

“‘Women don’t ‘normally’ walk around naked,’” Susan replies.

Faludi doesn’t care that her father is trans—what she does care about is her father’s unabashed appropriation of female stereotypes. “Change your clothes all you want,” she thinks when first meeting Stefánie. “You’re still the same person.” Her anger has nothing to do with her father’s change but with her concern that Stefánie is attempting to exonerate herself of being a horrible father by becoming a woman. “As I confronted, nearly four decades and nine time zones away, my father’s new self, it was hard for me to purge that image of the violent man from her new persona,” Faludi writes. “Was I supposed to believe the one had been erased by the other ...? Could a new identity not only redeem but expunge its predecessor?”

“In the Darkroom” is most insightful when the narrative structure of the memoir reflects the dyadic conceptual logic of the book’s central theme: identity. Dialogue is what brings father and daughter together; dialogue reestablishes a connection. Dialogue is also what allows both Susan and Stefánie to develop more nuanced understandings of their identity markers. “As much as [the memoir] is about my father’s transgender journey, it’s not ultimately about transgenderism as it is about identity in its multiple forms, and that we’re at a moment when identity is the battlefield,” Faludi tells me in an interview.

What Faludi proves in “In The Darkroom” is that identity is the starting point, not the end point, of conversation. It is something that emerges and coheres out of dialogue, or interaction, between the self and the other. “For me,” Faludi says, “my identity seemed to take shape in resistance to what the culture was dictating my identity should be."

"Perhaps it’s just my own perversity,” she laughs. “But others may have another similar identity formation.”

When asked if she would then define identity as a reaction formation, she pauses. “Well, I think that it’s very hard to live without categories... We all need some level of feeling tethered and belonging,” she says, noting how identity functions as way to build communities. “And yet so often, particularly modern identity seems to be about saying, OK, I’m going to put all my chips on this one identity marker, and that’s it. And now I don’t have to think about it anymore, or inspect myself anymore, or deal with any of my complicated internal psychology that is shaped, in fact, by the endless number of dynamics from one’s history to the culture you live in.”

“What was unusual about my father was that she was kind of like an identity zealot,” Faludi says. “Her life was spent up against one after another era defining identity crisis, whether it was being Jewish during the Holocaust, or trying to be the All-American suburban commuter dad during the depths of the postwar ’50s—the masculinity crisis era.” (A nod to her own study of the crisis of American masculinity, “Stiffed.”) “Or going back to Hungary, and trying to fit in again. Or being a trans woman in a country that could not be less friendly to trans people.... My father’s life was uncanny [in] how it touches on all these identity fronts that have been consuming our world for at least a century.”

“My father and I certainly disagreed with how [she] and I defined womanhood,” Faludi admits. “I’m not fan of 1950s femininity. In the end, my father, while very extreme in her notions of clichéd femininity in the beginning, came to do something more in-between and indeterminate. At the very, very end, she started referring to herself as trans rather than ‘I am a woman.’"

"In that way, and in seeing my father take that trajectory, I affirmed my own feminism, which is based on gender being fluid, and that we exist on a continuum and that there is no one way of being a woman,” Faludi adds.

“I don’t buy into any kind of essentialism or singular identity,” Faludi explains. “And in that I think I’m pretty much in agreement with contemporary trans theorists that gender is on a spectrum, and that you can’t make these judgments on an identity through the lens of one person. No one is defined by one identity.”

In many ways, “In the Darkroom” is an exemplary feminist memoir because the story crystalizes around two women who face each other, and who in turn arrive to deeper, more nuanced understandings of themselves and one another through their engagement. As the late "The Feminist Difference" author Barbara Johnson wrote, “as long as a feminist analysis polarizes the world by gender, women are still standing facing men. Standing against men, or against patriarchy, might not be structurally so different from existing for it. . . But conflicts among feminists require women to pay attention to each other, to take each other’s reality seriously, to face each other.”

“This requirement that women face each other may not have anything erotic or sexual about it, but it may have everything to do with the eradication of the misogyny that remains within feminists, and with the attempt to escape the logic of heterosexuality," wrote Johnson. "It places difference among women rather than exclusively between the sexes.”

When I read this quote to Faludi, she immediately saw the connection. “I love thinking about that quote in the context of my relationship with my father, which went from a childhood of reacting against him as the ur-patriarch to the two of us facing each other, talking about what it means to be a woman.” She continues, reflecting upon her father’s life, “the other side of this is an extension of this idea that Johnson talks about is also seeing the ways that men are trapped by a patriarchal construction.”

This observation holds true for Faludi's father. Shedding the stifling strictures of masculinity enabled Stefánie’s own journey of release and reunion — not only with her daughter, but with herself. “Whatever the original reason she was conscious of her having or making her gender change in the end,” Faludi observes, “what mattered to her, and what I heard her say over and over again, was that she could communicate with people now. To break out of that isolation was a serious win for her.” Stefánie’s change was her liberation.

“My father is not the poster child for trans,” states Faludi. “We need more than poster children. Trans rights should not depend on every trans person being exemplary. Stories that are individual, that are particularistic, and distinctive — like my father was — are important.”

Shares