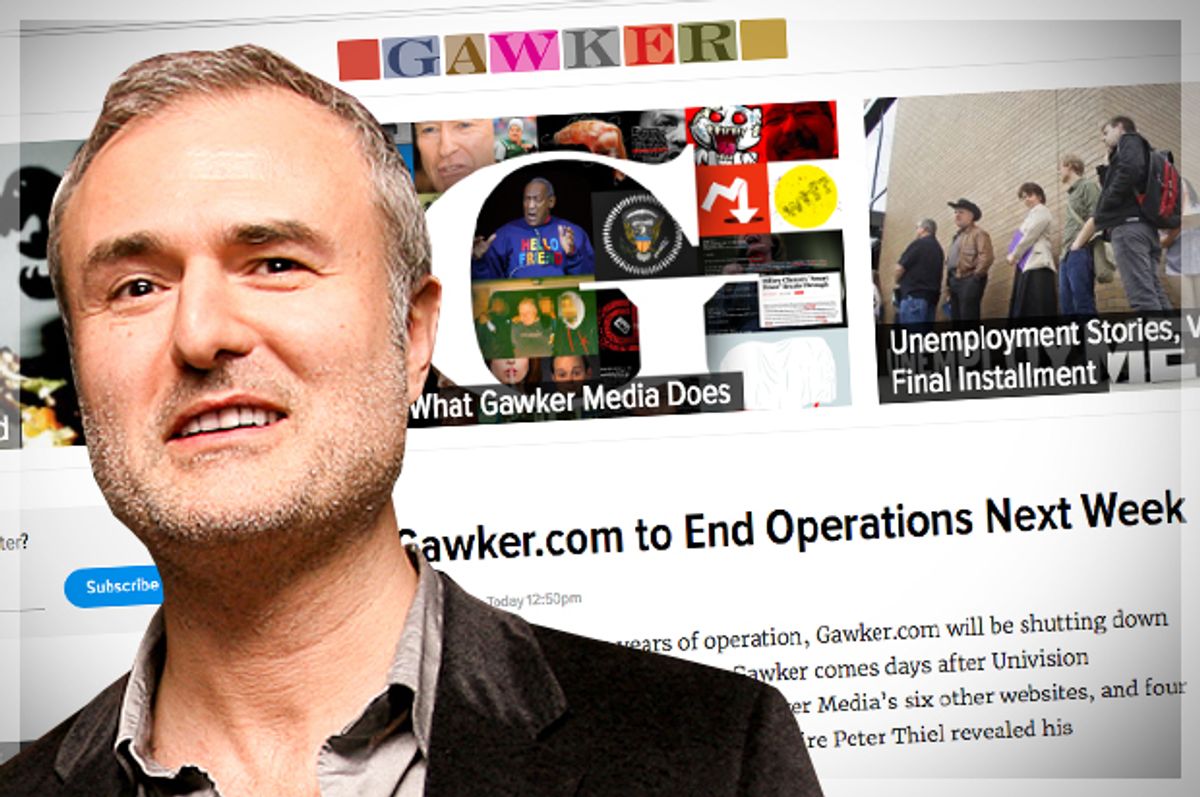

In a move that now seems both shocking and almost inevitable, the site Gawker announced on Thursday that it will suspend publication almost immediately. The news came shortly after the larger Gawker Media empire — which had been brought to its knees by the unlikely tag team of professional wrestler Hulk Hogan and Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel — was saved by a $135 million bid by Univision.

Gawker itself reported the news this way:

Nick Denton, the company’s outgoing CEO, informed current staffers of the site’s fate on Thursday afternoon, just hours before a bankruptcy court in Manhattan will decide whether to approve Univision’s bid for Gawker Media’s other assets. Staffers will soon be assigned to other editorial roles, either at one of the other six sites or elsewhere within Univision. Near-term plans for Gawker.com’s coverage, as well as the site’s archives, have not yet been finalized.

The news was met with a wide range of reactions.

Was Gawker good for America, for journalism, for “the media,” for the Internet? Damn good questions and damn hard to answer — because the site demonstrated some of both the best and worst of 21st century journalism.

Most infamously, Gawker outed not just an noisy and unpleasant tech mogul whose homosexuality was an open secret in Silicon Valley — and who later and funded a bankrupting lawsuit — but a reasonably private magazine-publishing CFO who was married and the father of three.

Gawker also did serious work, and showed very little deference to the kind of powerful people who sometimes evaded real coverage. (Given the hero worship with which tech moguls are often treated, the tough coverage of Thiel was valuable, even if the outing is hard to defend.) The site has been blowing its own horn lately — here are some pieces Gawker wants to be remembered for. This includes associated sites like Jezebel and Gizmodo, which are likely to continue publication under Univision.

Gawker itself helped break the news of Toronto Mayor Rob Ford’s use of crack cocaine and Hillary Clinton’s employment of a private email server. It published some agenda-setting pieces, like Tom Scocca’s essay on smarm — a piece worth reading even if you don’t agree with its advocacy of snark. Gawker's series of stories from unemployed people could be poignant and important.

A number of talented reporters and editors got their start at Gawker or stopped there along the way, including Adrian Chen, now a staff writer at The New Yorker. (Chen has called the Hogan/Thiel vs. Gawker mess “a drama that resembles something that Trey Parker and Matt Stone might imagine if they were commissioned to write a musical about the First Amendment.”) The roll call becomes much larger if you include staffers from associated sites, such as Will Leitch, formerly of Deadspin, or Anabelle Newitz, former editor of io9 (where I briefly contributed.)

Elizabeth Spiers, Gawker’s founding editor, who went on to the New York Observer and other adventures, is proud of the 10 months she spent at the site in 2003. “We could be really experimental about what we were doing,” she told Salon, recalling an age when blogs and media sites were still outliers. “Nick viewed Gawker as the property that was the most mutable, so it could turn on a dime.”

So why are so many people — even some journalists — gloating over Gawker’s imminent disappearance? Part of it is that Gawker would routinely mock other writer’s work in its stories in a cheap, name-calling way. Vanessa Grigoriadis wrote in 2007 that the site was “about the anxiety and class rage of New York’s creative underclass… on a most basic level, it remains a blog about being a writer in New York, with all the competition, envy, and self-hate that goes along with the insecurity of that position.”

Part of is that its ethical compass seems a bit unsteady, especially in the case of the outings. Spiers says that the CFO’s outing “was horrifying to 99 percent of the people who work at Gawker, and horrifying to Nick.” To judge the site by that, she says, is like assessing Rolling Stone magazine based on its misfired story about rape at the University of Virginia.

Even if you think celebrities should not be treated like demigods, the “Gawker stalker” (a running map of celeb locales the site introduced as “the next step in inane celebrity drooling”) was pretty disgusting.

Part of it is that any journalistic site is destined to anger powerful people, and that’s something Gawker did well and often.

The other reason is the Gawker tone — that patented combination of digital era-snark, media-insider-know-it-allness, old-fashioned nastiness, an ironic smugness that makes early David Letterman sound earnest. While other publications — Spy magazine, for instance — contributed to the making of the Gawker voice, the site took it further and applied it not just to famous or powerful people.

Spiers describes the site’s original tone as knowing and irreverent but less mean, and explained that in the years after she left, a tabloid voice entered into much of the site’s stories. Gawker never had a house style, she said, but some of its pieces could be nihilistic and derisive, and it sometimes demonstrated “a harsh tone that seemed humorless,” which temped some readers to unfairly dismiss it.

In the same way the inflexible views and shouting of Fox News spread around most television news programs, regardless of their ideology, so the smug bitterness of Gawker gradually transformed the Internet’s mainstream.

If Gawker had gone down because people stopped reading it, its demise would be met with less regret. But while we don’t know exactly why Univision chose to shutter Gawker, there seems to be two main reasons for the site's impending demise. The first is about money: Thiel’s ability to nearly destroy a media empire by funding a single lawsuit shows just how vulnerable publishing is in the 21st century. Specifically, an independent site without overwhelming advertiser appeal that trades in aggressive reporting and a giant-killing mission is not a terribly solid business proposition.

The second reason for its cratering is as hard to document as it easy to intuit: The Gawker tone — good, bad, and ugly — has seeped into the media groundwater and permeated the cultural conversation. We don’t know how Gawker itself would have changed if it had been able to go on living; Denton expressed some regret after the CFO scandal, and suggested the site might rein in its vindictiveness and loose ethics. But we’ll never know. Once the corrosive Gawker tone, the vicious Gawker vision, is all over the Internet, who needs Gawker?

Shares