It’s a bit like a beloved Reagan-era rock band getting back together after decades of silence. Berkeley Breathed, creator of “Bloom County,” had not stopped writing and drawing since the strip's 1989 conclusion. But he’d done nothing as popular and zeitgeist-y as his comic strip starring a mix of humans and talking animals tossing out pop-culture-inspired wisecracks in a fictional small town.

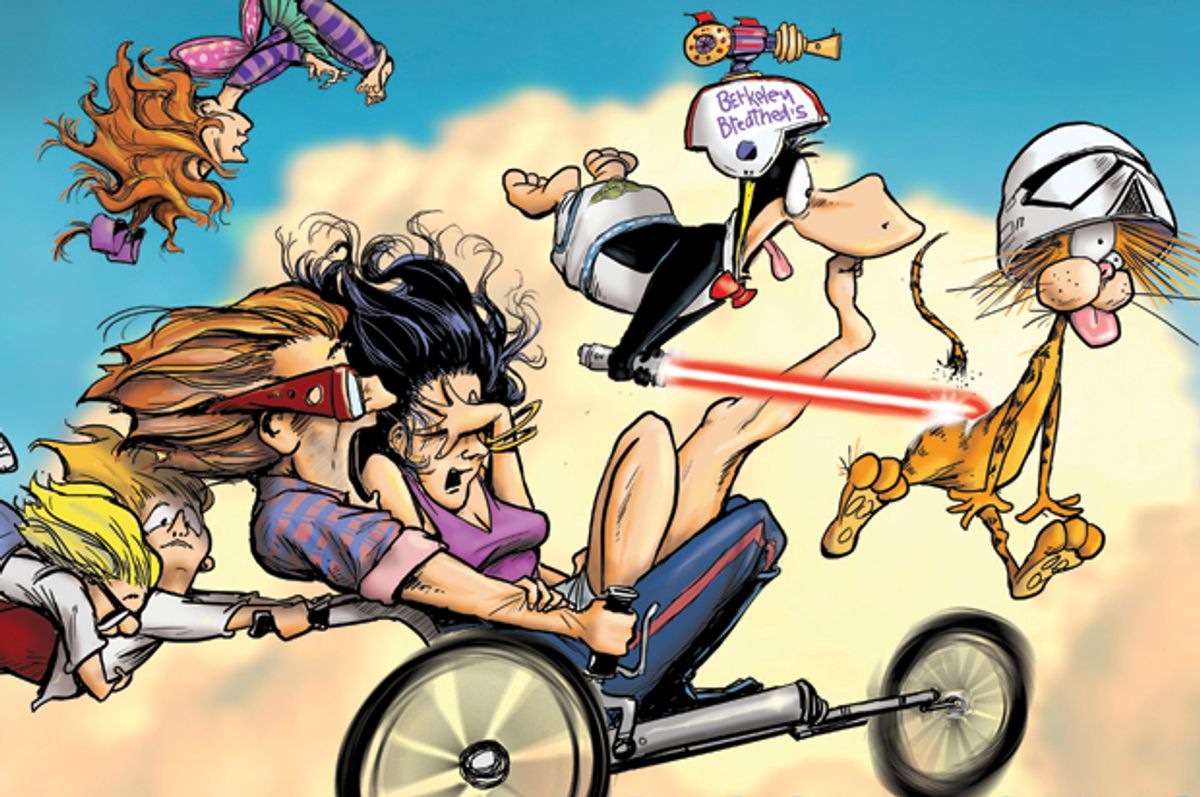

And the return of “Bloom County” — which Breathed revived last July, with no warning, as an online-only daily strip on Facebook — is now in print, as IDW Publishing brings out a book of the new strips: “Bloom County Episode XI: A New Hope” comes out September 13. A picture book for young readers, "The Bill the Cat Story: A Bloom County Epic," will make its debut from Philomel Books on the same day.

“Early and Late Bloom County should be worth a week in some future bullshit college course on pop history,” Breathed told me by email, his preferred way of communicating. “Nobody has done this before — start strip, stop strip, start family, see world, get old, watch world become digital, start strip again. So it is sorta intriguing. Remember, Bloom County became of age when I was barely out of college. I ended it at an age most college kids now graduate and finally leave the house. Read: what the hell did I know?”

A lot has changed about the world since “Bloom County” made its debut in newspapers — through the Washington Post Syndicate — in December of 1980. Jimmy Carter was still president, though he had been defeated in an election the previous month. Newspapers were thriving, and the internet barely existed. “Miami Vice” had not yet aired, MTV was still a year away and neither Madonna’s debut nor Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” had come out. “Star Wars” was in between films in its initial trilogy. (No one knew what a “prequel” was at that point.)

The popularity of the original comic may’ve come from its distinctive tone. The strip was satirical, but unlike “Late Night With David Letterman,” which would launch in 1982, there was nothing bitter about it. With the exception of Steve Dallas — a jaded, shades-wearing playboy lawyer — the characters were mostly sweet. Milo, Cutter John, Binkley and Opus the penguin (who gradually became the dominant character) brought a warmth to the comic. And the absurdity of the story lines, a general knowingness to the characters and oddball figures like the eternally freaked-out Garfield parody Bill the Cat, kept it from becoming cutesy.

The strip was intensely loved by its fans in a way that had few parallels, says Tom Spurgeon, who runs The Comics Reporter blog. “It went beyond even the following for ‘Doonesbury,’” Spurgeon says of Garry Trudeau’s classic politics-focused comic. “It’s an interesting achievement for a satirist, for someone who’s taking shots at society, to have that kind of affection.” It was also massively popular, running at one point in more than 1,200 papers, which put it in front of 40 million readers.

“Bloom County” would be linked, for a lot of people, to the Trudeau strip: For one thing, the two comics looked alike, and Breathed’s strip filled the vacuum for many newspapers when “Doonesbury” went on hiatus for most of ’83 and ’84.

Breathed, for what it’s worth, says the only two strips he’d read before starting his were “Doonesbury” and “Peanuts”; this may, at least in part, explain his strip’s originality. “There had been fantasy strips, like ‘Peanuts’ and ‘Pogo,’ “ said Chris Mautner, who writes for Comics Journal and The Smart Set. “But they didn’t have the goofy, weird quality. [“Pogo” creator] Walt Kelly would never have had things like ‘the anxiety closet,’ or the characters forming a heavy metal band. Breathed struck me as someone who was very tickled by the absurdity of ‘80s culture.”

Breathed says his strip’s roots come less from other comics and more from the small town in Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.” And some of his sensibility, he says, comes from Douglas Adams, author of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” and Monty Python’s John Cleese. (Both were Englishmen who moved to California, where Breathed lives, and eventually became friends.)

After the closing down of the original “Bloom County” — Donald Trump became a character and, in 1989, bought out the strip and fired the other characters — the comic went on to become an important influence. “There was a time when every college comic had a guy in sunglasses nobody liked, talking animals, and characters who addressed the audience,” Mautner said. He sees its influence in many web comics. And Aaron McGruder of “Boondocks” — the strip, about a black family in a white town, that started in 1996 and later became an animated series — has praised Breathed’s influence.

But despite the fondness with which many remembered “Bloom County,” Breathed’s related strips — “Outland” and “Opus” — didn’t quite catch fire.

What did happen to bring Milo and Opus and the rest back into visibility was IDW’s publication of “Bloom County” in a series of hardback books, part of a larger wave of comics, as familiar as “Peanuts” and as obscure to American readers as “Moomin,” receiving deluxe repackaging.

Though the revived strip includes a few political references, including some to Trump, Breathed has been cagey about how much the candidate inspired the return. “This creator can't precisely deny that the chap you mention had nothing to do with it,” he wrote to a fan on Facebook. And he told me that Trump is both a natural and difficult part of his comic: “He’s a cartoon character, duh! As my son would say. Which is another way of saying that he is untouchable in most typical satire. ‘SNL’ and the nightly talk shows should just stand down. I am.”

The explanation he gave The New York Times last year for his strip’s return turned on politics, though:

Deadlines and dead-tree media took the fun out of a daily craft that was only meant to be fun. I had planned to return to Bloom County in 2001, but the sullied air sucked the oxygen from my kind of whimsy. Bush and Cheney’s fake war dropped it for a decade like a bullet to the head. But silliness suddenly seems safe now. Trump’s merely a sparkling symptom of a renewed national ridiculousness. We’re back baby.

But Breathed now says he’s trying to move the strip away from political issues. “I’m toiling to make it less so,” he wrote. “It is not easy. That’s not a glib answer. Like everyone, I struggle with the fascination/repellant push and pull of it all. The repelling is winning at the moment. So too with my readers, I sense. They don’t mind paying attention to it all in their peripheral cultural vision… but they don’t much like keeping it straight in front of their retina every day. There’s a spiritual context to it all, although I really hate that I said the word ‘spiritual.’"

The new strip resembles the old one pretty closely, with its familiar cast of characters, but now with references to the “Star Wars” sequels, electoral politics, sex tapes, the burkini, yoga and the unpleasantness of air travel. But there’s a broader difference.

“In the recent strip there are a lot of times the characters are bewildered or confused,” Spurgeon said. Sometimes the strip is less funny, but it has a warmer tone. “It has an appealing fragility and vulnerability. It’s comforting when the smart ass is confused, too. There’s so much anxiety in the air. This is a little gentler and a little more human.”

One other difference is that by posting on Facebook, Breathed is not making any money on the strip outside books and other licensing. “I do this mostly for free at the moment,” he said, explaining that he had turned down half a million dollars from a newspaper syndicate, "just to play the martyr for art."

Breathed also told me he has a new approach to the strip:

Some new rules now: no celebrities get snark treatment unless they actually commit snark offenses. Being imperfectly cool with their art, for instance, doesn’t reach that bar. Another rule: avoid celebrity humor altogether. I had it [to] myself in 1982. A bit busier a quarter of a century later.

Probably most important is the Dukakis rule: political humor has a half-life similar to a mayfly. Be sparing with it. More: It’s largely without nourishment. Politics actually means very, very little in people’s lives.

What he does want to capture is the new social conditions he’s picking up. “I smell a quantum shift in the world right now that is unlike other revolutions,” he wrote. “We’re realizing that nobody is actually behind the green curtain pulling the levers on the special effects of the Great Wizard. Its a reckoning with how close chaos actually is, around every corner. Trump is a glimpse. Isis and the allure of suicidal nihilism is another. People are nervous. It’s a good time to be in my business.”

Shares