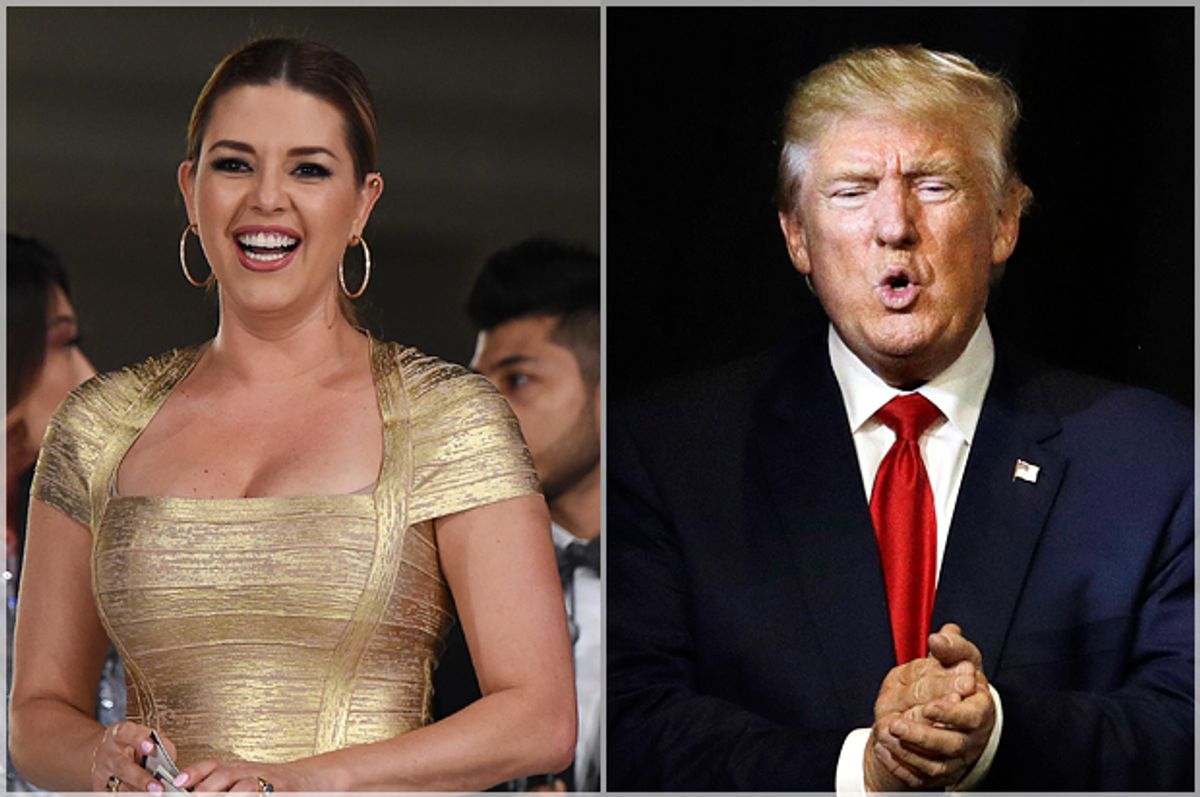

In the final moments of the first presidential debate, Hillary Clinton turned to her rival — a man who had interrupted her at least 51 times in an hour and a half — and called him out for smearing women as “pigs” and “dogs” and specifically for referring to Alicia Machado, a former Miss Universe, as “Miss Piggy” and “Miss Housekeeping.”

When that happened, I texted to a friend that this was Donald Trump’s “Ezekiel 25:17 moment.” That, according to Jules Winnfield, refers to when the “Pulp Fiction” hitman played by Samuel L. Jackson delivers that infamous verse about righteousness: “If you heard it, that meant your ass.”

And it has meant Trump’s ass — at least with the mainstream media and broad swaths of voters. Within 48 hours of the debate, Machado was mentioned in more than 150 print articles, more than 6,023 times on television and over 200,000 times on Twitter. After the debate, Democratic nominee Clinton has been edging up in polls from some much ballyhooed battleground states.

In a week that saw its share of potential scandals — including reports of legal inquiries into the Republican candidate's charitable organization, the Donald J. Trump Foundation — the story of Trump in his capacity as then-owner of the Miss Universe pageant forcing Machado to jump rope in front of reporters as he quipped, “This is somebody who likes to eat,” took root more deeply than any other.

Headlines like “15 Times Donald Trump Fat-Shamed Kim Kardashian, Jennifer Lopez, and More” and “400 Pound Hacker? Trump Comments Fuel Dialogue on Fat-Shaming,” in reference to Trump’s observation during the debate that threats against “the cyber” might not come from Russia but “somebody sitting on their bed that weighs 400 pounds” have arguably eclipsed allegations that he violated the Cuba business embargo.

Then again, the intensity of these reactions should not be surprising, given our culture’s neurotic fixation with weight — one that forces every woman through a crucible of fashion spreads and movie babes and fitness stars and, yes, TV beauty pageants that create the illusion of a Zen-like, aspirational state of thinness that conveys beauty and grace, love and empowerment and perfect health.

Watching the video footage of a young Machado doing aerobics as the flashbulbs pop, her face drawn into a taut mask of forced buoyancy, I remembered the heat in my cheeks when the boys on the playground pelted me with small pebbles, shrieking “Free Willy!” And I recalled when my crush from fifth-period biology class got on one knee to ask me to homecoming and how, for a moment, I was electric with hope until, of course, I heard his friends snickering. And I remembered when the catcaller in front of my office yelled, “Damn, you sure do love to eat!”

I can imagine what Machado might have been thinking as Trump told the throng of camera people that “she went up to 160 or 170” pounds, with the disgusted solemnity of a scientist in a horror movie, explaining how radioactive waste created the monster: Don’t cry, don’t break, don’t let them know that they’ve hurt you.

But they do hurt you and badly. Like Machado and more than 30 million people in the U.S., I strapped myself to a breaking wheel of binging and purging, starving and popping pills, until I was ground down to pulp and bone. To reclaim my life, I had to armor my heart against a culture that reviles my body, a culture that finds its megalomaniacal megaphone in Donald Trump and his crusade against the “Miss Piggies.”

The daily barrage of Trump-isms about fatness is deeply triggering. And yet one could argue that the media coverage indicates a crucial shift in how we think or at least what we’re allowed to say about bodies and size: The blitzkrieg of outraged think pieces, indignant headlines and incredulous TV hosts — including the crew at “Fox & Friends” who sat in slack-jawed horror as Trump doubled down on his size bigotry after the debate, reiterating that Machado’s “massive” weight gain was “a real problem” — is light-years away from that 1997 media scrum that turned the young woman jumping rope under the hot lights into a dancing bear. I want so badly to believe that the frothed-up news and entertainment industry — as well as the furious anger spreading across social media — indicates a real change.

So much of this change, however, seems focused on insulating Machado and other Trump targets like fellow Miss Universe contestants or Kim Kardashian from being besmirched as actual fatties. At 160 to 170 pounds, Machado was actually at the goal weight I broke myself to achieve, only to fall short of. She was then, as she is now, thinner than many American women. As Sarai Walker, writing for the Washington Post, put it, “This is a story about a woman who was ‘called fat,’ in this case a thin woman. This is not a story about a fat woman.”

Though Trump has repeatedly and expressly mentioned his sizeist scorched-earth campaign against Rosie O’Donnell, she is not a beauty queen and hasn’t apparently merited the same degree of attention or sympathy. So I highly doubt that the electorate would have rode out White Knight-style against Trump’s debate-night fat shaming if that shaming happened to, say, a former employee who looks like me: size 26, with hips that spread whenever I sit down.

Our cultural consciousness may have rejected the heroin-chic skinniness that dominated the mid-'90s. We may spread the gospel against Photoshopping models and actresses and pump our fists to songs like Beyoncé's “Pretty Hurts” but the old standards that equate fatness with ugliness, laziness, stupidity and even moral failure still thrive.

Only now they are couched in messages about health and wellness, about living your sassiest, most satisfying and, yes, your “best” life. Much of the rah-rah jingoism surrounding the body positivity that lauds Jennifer Lawrence as a real-life heroine for gushing about her love of pizza, rallies behind Victoria’s Secret supermodel Gigi Hadid for proudly proclaiming that she has “boobs [and] a butt” and praises Amy Schumer for insisting that she not be airbrushed on the cover of Entertainment Weekly (even as she boasts that she’s a “proud size 6 yo”) is about saving “normal,” “healthy” and “curvy” women from the damnation of actual fatness.

The rings of Fatness Hell include job discrimination, life-threateningly inadequate medical care, mockery within almost all forms of entertainment and daily public humiliation. The holy light of body acceptance doesn’t redeem people with actually fat bodies.

That’s how I knew that as soon as Clinton mentioned Machado, it meant Trump’s ass. The smoke wisping off her gun barrels was not only our collective revulsion at a powerful man using his position to humiliate a vulnerable young woman. Some were reacting to their own memories of being hectored and bullied. Others were also unmistakably swept up in the great fury and fear that if a woman who looks like Machado could ever be considered fat, then so could they.

The Clinton ad featuring Machado explains this terror perfectly, if perhaps unconsciously, through one of the tabloid captions that appears after a clip of Miss Universe working out under the watchful eye of the press: “Beauty treated like a beast.”

Size-based bigotry is one face of the many-headed hydra of Trump’s misogyny and taking a sword to its neck is vital. Alicia Machado is a hero for running back into that monster’s den and subjecting herself to Trump's insults again. Some champions of the "you go, girl" rhetoric about body positivity who set out to castigate Trump, however, ironically end up reinforcing his views that to be fat is to be less of a woman and less of a person — a beast.

I have read well-meaning articles that make statements like “the thing is that fat-shaming doesn’t help people get thinner, and the stigma it creates does more damage than good,” which may superficially seem to be challenging diet culture but in fact only affirm size acceptance in its capacity to help people become “healthier” in fairly conventional ways. In August, Sara Benincasa’s master class in clapping back at a man who had written her to ask her why she had gained “so much weight” went viral: It appeared across my social-media feeds with an assortment of “yes!” and “this!” — and rightfully excoriated the reader who presumed that Benincasa’s body was in any way his business.

I’m with Lesley Kinzel, however, in her hope “that the people giving props to an average-sized woman saying fuck you to uninvited commentary would give the same props to someone much fatter” and in her sad suspicion that when "a woman in a size-10 dress is castigating the establishment that finds her body unacceptable, many of those people who wouldn’t make eye contact with me? They’re cheering for her.” Size acceptance is possible only when you’re an acceptable size.

Even though Machado and I are separated by many dress sizes, we have both borne the scarlet F. The difference is, of course, that she can slip free from the label and I can't. In order to fully vanquish the Trumpian malevolence that harms women of all sizes, we need to promote body positivity that not only extends empathy to Alicia Machado for failing to attain some higher level of so-called perfection (and to the average woman who is desperate to look like Machado even at her “fattest”) but also to a woman like me, who is unabashedly, unapologetically fat.

Where is the great vengeance and furious anger for us, when every day, online and in the real world, we must walk through a gauntlet of hatred and abuse? We need more than simply “size acceptance.” We deserve respect, protection and even celebration.

Shares