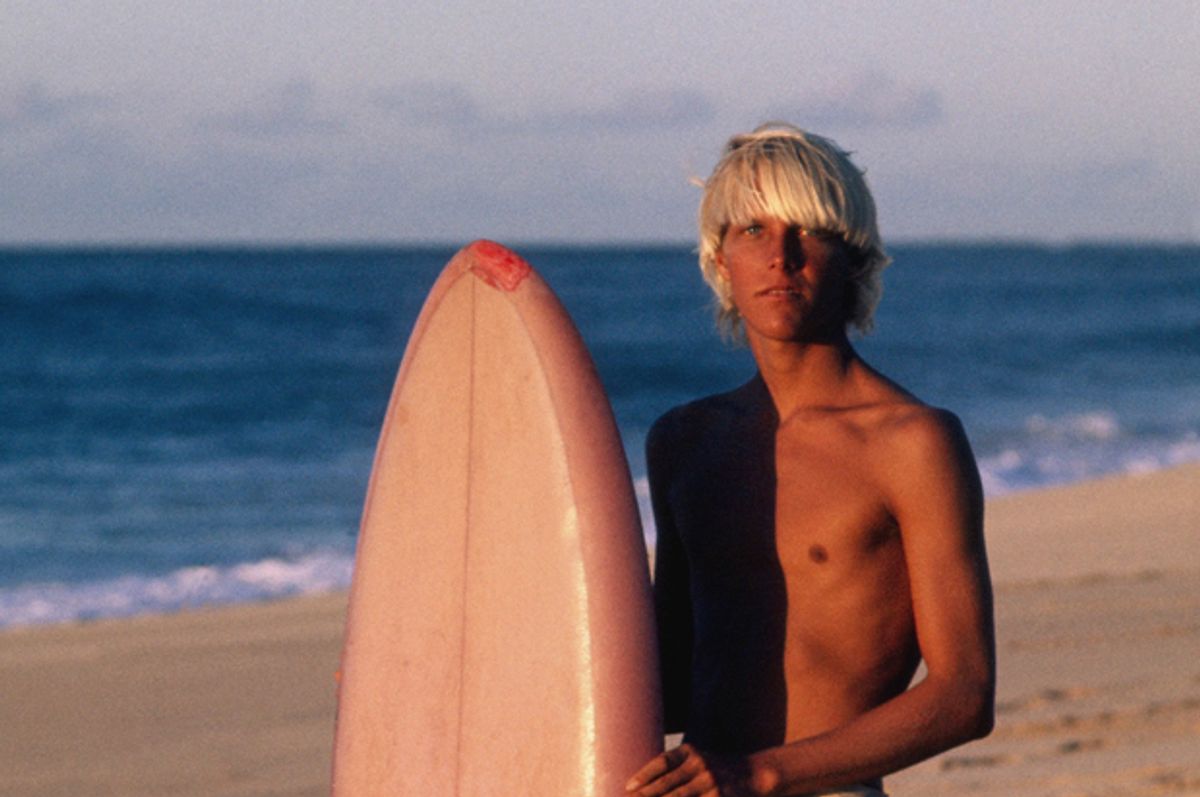

Bunker Spreckels was a wild, colorful man. The scion of the Spreckels Sugar Co. and the stepson of Clark Gable, he was a surfer, a hunter and a jet-setting playboy, who inherited millions at age 21. He traveled to South Africa to surf; met his girlfriend, Ellie, in Biarritz; and often dressed like a pimp. He did copious quantities of drugs, traveled the world and died, in 1977, at age 27.

Takuji Masuda’s captivating documentary, “Bunker77,” uses archival footage and photographs, along with interviews with Bunker as well as his friends, including surfer Laird Hamilton and skateboarder Tony Alva, to recount the life of Spreckels, who has been dubbed “the most decadent person in surfing.”

Masuda spoke about his film and the under-known surfing legend with Salon.

Are you a surfer?

Yes, I am a national champion from Japan and I used to be on the world tour as a professional surfer.

How did you first hear about Bunker and what made you turn his story into a documentary?

Back in 1994, when I was surfing professionally, I met my co-producer, Art Brewer, who is one of the most famous surf photographers. I was one of his subjects. In the surf world, it’s very normal to tell stories about surfers and he kept telling me about his encounter with Bunker Spreckels. It stuck with me.

Around the same time, “The Surfer’s Journal” came out, and there was a mention in it of Bunker at Jeffreys Bay in South Africa. I kept asking Art more about him because they were all using his recollections as well as his images and [an interview presented in the film] from Craig Stecyk.

A couple of years into surfing professionally, I was drawn into publishing amazing stories from the beach culture, so I published the magazine, “Super X Media.” I asked Art Brewer and Craig Stecyk along with Glen E. Friedman, co-author of “Dogtown: The Legend of the Z-Boys,” and Paul Haven, an art director, to work with me. We did a literature review in my magazine on Bunker and at the tail end of this publishing effort, a Taschen book, “Bunker Spreckels: Surfing’s Divine Prince of Decadence.” I asked Art and Craig if they would be OK with me pursuing a film version, and that’s how the documentary started.

This is your first film, and you deftly incorporate family footage and photographs, film clips, animation and interviews into the narrative to tell Bunker’s story. Can you discuss your approach and how you wanted to present this biographical portrait?

This is my first time directing a long-form film. Five years into it, I had very linear, one-dimensional documentary, and I felt my subject deserved better. Around that time, which was seven years ago, I was serving on the board of my alma mater, Pepperdine, and I was excited to support a film and media program on the campus. I decided to enroll myself in it and bring my half-baked documentary with me.

The curriculum allowed me to ask deeper questions and review other people’s work and scholarship. Viewing my film through an academic lens helped me have a dialogue with the audience and share a point of view beyond Bunker’s life story. When I started, I had no idea I would be able to have that kind of approach.

There is considerable discussion in the film about Bunker not having an appropriate father figure. that his dad died when he was 11 and his stepfather, Clark Gable, passed away shortly thereafter. He was mentored by Miki Dora and became a mentor to Tony Alva. He obviously paid it forward. What do you think about his relationships with father figures?

We all have complex relationships with our fathers — living up to their achievement or doing better than them. Or they have an expectation for you. There is an expectation in Bunker’s familial lineage. I have a 7-year old son, so it was good for me to ask what it means to be a son as well as a father.

Bunker came from a famous family and was stepfathered by one of the most famous men of the time. Because both fathers died when he was 11, he was longing for a father figure. He didn’t want to replace his [dads], but that was his journey.

At 19, pushing 20, he lived an almost nomadic life, first in the forest, then being taken in by Laird Hamilton’s family. At 21, he inherited millions and could fend for himself. Do you think that money was a curse, or a blessing?

He didn’t seem to have much guidance. He created his own path, away from what was “normal” in his family. His mother was preoccupied caring for his [decade younger] half brother. He had resources, so he was able to live an original life. I’m sure his mother’s advisors tried to guide him, but he went his own way. He was deprived of a traditional familial setting and was underprivileged in a way.

He also reinvented himself several times. He wanted to be in a band. He learned hunting. He dabbled in film even working with Kenneth Anger. He dyed his hair black and partied hard. What do you think accounted for his wanting to “play” so many roles?

He was trying to find out who he was. Resources allowed him to do it immediately; the rest of us have limitations. He had access to conceptualize it and act on it. It makes his short life interesting because so much happens in so little time. He was trying to live up to expectations of being Clark Gable’s stepson and live down being the third-generation heir to the Spreckels’ fortune.

He had to reinvent and rebrand the Spreckel’s name. He was a significant person in the surf world besides all this reinvention. He felt he needed to keep reinventing and proving himself as a public figure in society. Maybe that’s universal — with Paris Hilton or the Kardashians — because they have to appear interesting. They feel like they have to behave a certain way.

He is known for his radical reinvention of surfboards, making them shorter. They are popular now but never quite caught on at the time. Do you think Bunker was ahead of his time?

Yes, definitely. Randy Rarick, the founder of the World Surf League at that time, said Bunker didn’t have to conform because he didn’t need to be paid or acknowledged in a magazine. He just pursued his joy — going fast in critical waves. He was avant-garde in that sense.

I get the sense from “Bunker77” that he was often fearless and almost always in control. Nevertheless, Bunker has to be “rescued from himself.” What can you say about his self-destructive nature?

I don’t know if he was ever in control. He was punk; he went for it. He wasn’t reserved and put everything on the line. That kind of spirit is worth noting. It’s kind of romantic. When you get too close to heroin, no one comes out of it with a happy story. Some see it as a cautionary tale, but Bunker didn’t have the opportunity to rehabilitate from that. He showed how destructive heroin is. Even today, we underestimate that vice.

If you could have met Bunker, what circumstances would be ideal?

When he was a surfer back in the 1960s. We have both surfed the same wave. I rode the longest board at [Hawaii's] Pipeline, and he rode the shortest. I put everything on the line like most surfers do to prove themselves and be accepted. That’s what we share. We share the same feeling of being a Pipeline surfer. I wish I could have shared a session with him because he was said to be so much fun to be around.

Shares