Critics of the 2002 James Bond film “Die Another Day” decried its over-reliance on über-tech, even by 007 standards. Think sonic agitator rings for shattering bullet-proof glass, and an invisible Aston Martin that might as well be, according to one reviewer, “a Harry Potter car.” The pièce de résistance: a satellite capable of harnessing solar power from outer space and beaming it back to Earth. But disillusioned Bond fans of the early Aughts should take heart — experts say that last bit of pie-in-the-sky tech is about to get a whole lot more realistic.

This is not the stuff of a tense sci-fi plot — we really do need a new way to power civilization. The fossil fuels that meet 84 percent of America’s energy needs are running out, and in the meantime they’re destroying the planet. Considering our energy needs are expected to double by 2100, we’re in trouble.

Yes, renewable energy technologies exist. But solar power, the one with arguably the most promise for significant, scalable deployment, is intermittent. Although the sun provides more energy in one hour than humans consume in a year, we can only tap into this power when the sun is shining. At least, that’s been the predominant school of thought.

But since the 1960s, a group of researchers from NASA and the Pentagon have been thinking outside the box — or in this case, outside the atmosphere. Solar power captured in outer space would not be limited by nighttime hours or cloud cover. And — unlike 23 percent of current incoming solar energy — it wouldn’t be absorbed by water vapor, dust and ozone before reaching us. Finally, because space solar is constant, it wouldn’t need to be stored, which can lead to energy losses of up to 50 percent. In other words, taking our solar panels from the ground to the cosmos could be a great deal more efficient. It may also be key to humanity’s survival.

“In countries right now where they’re trying to deal with poverty, water scarcity, poor health, lack of education and political instability -- these are all things you need energy in order to fight,” Paul Jaffe, PhD, spacecraft engineer at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, said in a recent TakeApart story. Or, as John C. Mankins, founder of Mankins Space Technology and author of “The Case for Space Based Solar,” told Salon, “In the long run, renewable large-scale energy sources such as space solar power are essential to sustaining industrial civilization, and the long and increasingly high quality of lives that we enjoy."

"Without vast amounts of affordable energy, the human population would inevitably collapse down to much smaller numbers," Mankins said. "Without large-scale zero-carbon energy, human-driven climate change will result in the eventual destruction of ecosystems and human habitats worldwide.”

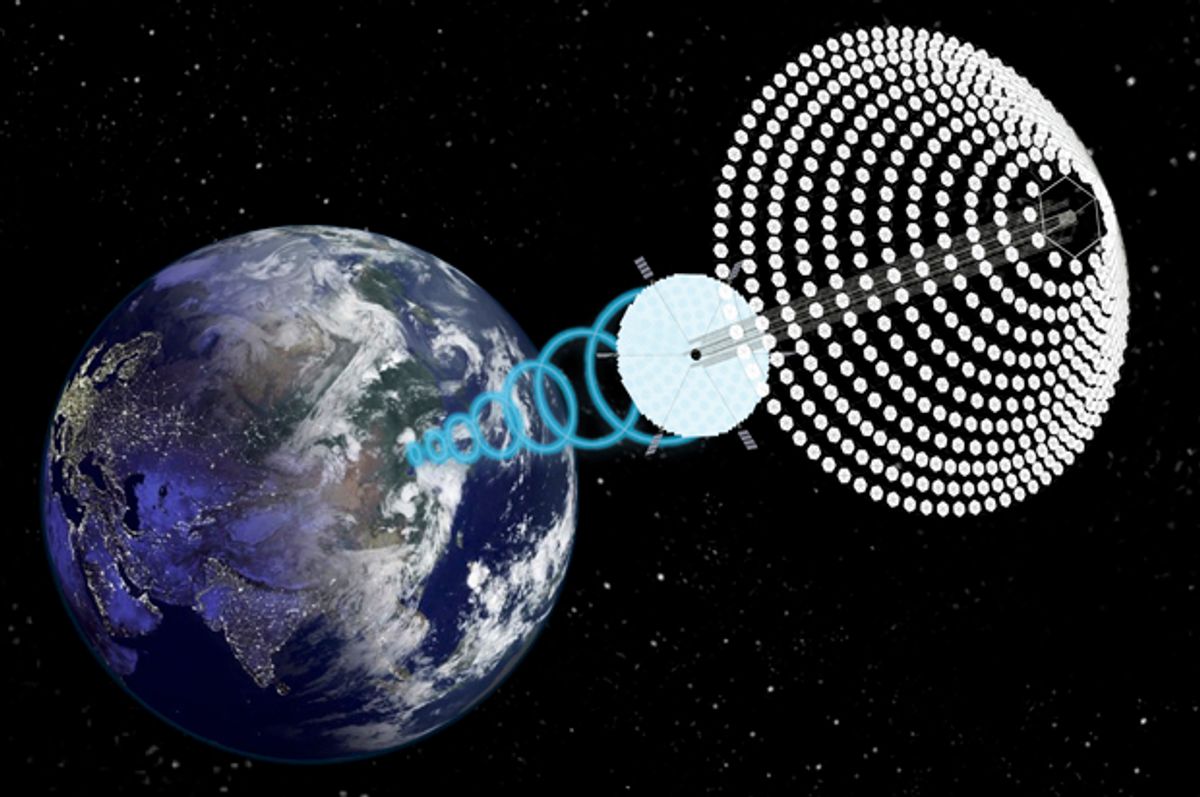

We already know how to make this work. With most proposals, large mirrors on a satellite will reflect sunlight into the center of the spacecraft where it can be converted to either laser or microwave energy before being beamed to earth. This beaming can happen uninterrupted, rain or shine, and at an intensity level no stronger than the midday sun, meaning birds and planes that get in the way aren’t in danger of frying. On the ground, power-receiving stations will collect this energy and feed it into the grid.

One of the major draws is that this space-based solar power can quickly and easily be transported in shipping containers to a specific site in need, like a new military base or disaster area. And we already have all the functional pieces necessary to get started — no new physics need to be discovered. It’s simply a matter of integrating them.

But not everyone thinks we should try. In 2012, Tesla’s Elon Musk told Popular Mechanics we should “stab that thing in the heart,” citing the high cost of deployment. But proponents believe the price of ignoring a clean, constant, global power supply — namely, ecological trauma and interstate wars linked to oil — could be much higher.

Because concern over climate change has intensified at the same time relevant technology has advanced, interest in space-based solar has risen in recent years. This past spring, the Department of Defense held the D3 Summit Pitch Challenge, in which government experts were invited to present ideas for meeting U.S. goals for diplomacy, development and defense. Out of 500 submissions, Jaffe’s plan for implementing space-based solar took home four of seven awards. In his presentation, Jaffe outlined the initial stages of development, which could be completed by 2021 for $350 million, or “about the same amount of money Americans spend annually on Halloween costumes for their pets.” The culmination of this phase would be an in-orbit plant capable of powering more than 150,000 homes for $10 billion.

“People look at space solar and say: ‘It’s not going to be cost competitive,’ ignoring the fact that there has to be maturation,”Jaffe told Salon. “Over time, things become more efficient. Wind and solar literally took decades to get competitive with carbon-based alternatives. I see similar potential here. In many ways, the future of space solar rests less on scientists and engineers, and more on people who decide what they want to pay for.”

Other countries are already ponying up. Japan foresees having a commercially viable space solar station in orbit within 25 years that will supply approximately the same amount of power as a nuclear plant. And China, the world’s largest energy consumer, plans on a commercially viable station in orbit by 2050, supplying the bulk of the country’s power. It will be twice the size of Central Park, and weigh approximately 10,000 tons — more than anything put into space to date.

In the U.S., the people behind California-based startup Solaren Corp. aren’t waiting on the feds to harness this power from the final frontier. According to a recent release, “Solaren has engineered zero emission electricity from space that is cost competitive with any terrestrial source of baseload electricity.” This year, they’ll complete the investment round that will allow for a design and demonstration phase, and they’ll do it with a major vote of confidence. In the first purchase agreement of its kind, the aerospace company has contracted with major electric utility provider PG&E to provide 200 megawatts of clean power from outer space over a 15-year period, beginning at the end of the decade.

Also in California, high school student Justin Lewis-Weber published a paper in the journal New Space this year that outlines a plan for putting self-replicating solar panels on the moon. According to Popular Science, “In the paper, Lewis-Weber calculates that it could cost tens of trillions of dollars to send up a meaningful number of solar power satellites… What if instead of sending thousands of solar panels into orbit, we could just send up one that’s programmed to make copies of itself?” Where would these robots get their necessary supplies? The surface of the moon, which they’d mine for aluminum, iron and silicon.

Some analysts believe this support from the private sector will help quell one of the major concerns surrounding space solar: that it’s merely a step toward the militarization of space and the weaponization of this technology. After all, before Bond saved the day, that solar-beaming satellite in “Die Another Day” was secretly meant to detonate a minefield, allowing for a hostile takeover of South Korea by its northern neighbor.

“But it all comes back to power density,” Jaffe told Salon. “These systems operate at a safe level, and you don’t have to worry about accidentally exceeding that, just like you don’t have to worry about running a marathon in an hour.”

And besides, if it’s another space race we’re concerned about, we’re too late — that spaceship has sailed.

Shares