I first heard of the Dakota Access Pipeline in mid-August. The story, like many others at the time, was being suffocating by an obstreperous presidential campaign that had just entered the home stretch. At first, I too had thought this was a Keystone XL one-off, soon to be swept away by the unforgiving cycle of news. But, after barreling half way across the country and trudging through over the frozen Dakota plains, I came to the realization that this story was riddled with oligarchic, environmental and indigenous oppression that was far more riveting than any pipeline story I had ever seen before.

In September, I was honored to interview LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, who told me the story of her people and provided me with true insight on the issue. She told me that the members of this movement should not be referred to as “protesters,” but instead “protectors,” because their goal was simply to protect their sovereign land, as well as their water. “I am not an activist,” she said.

Just a couple of weeks prior, police had unleashed dogs on the water protectors. Allard had gotten involved solely for personal reasons. She had lost her son, and he was buried on ground adjacent to the pipeline site. “I will not allow them to disturb my son,” she explained to me.

Inspired by Allard's story and commitment, I began to research Standing Rock. Soon I was furiously sharing stories about law enforcement using tear gas, shooting rubber bullets at protectors and journalists, conducting strip searches of those arrested and even putting some of the protectors in dog kennels. I discovered that some of the people acting as “law enforcement” worked for private security firm TigerSwan and had been hired by none other than the pipeline owners, Dakota Access LLC. Jim Reese, TigerSwan’s founder, has ties to Blackwater, a group of independently contracted mercenaries known for their covert and overt work in Iraq and Afghanistan. The more I learned, the angrier I became. The government of North Dakota is dependent on the oil industry, and I realized the decision to cease the pipeline was much more difficult than it should ever be. Still, the abuse at the protest sight seemed impossible to ignore.

The violence continued to escalate, and when the protectors were sprayed with a water cannon in subfreezing temperatures, and thousands of military veterans were making travel plans to North Dakota in order to defend protectors from further abuse, I booked an airplane ticket, both to witness Standing Rock for myself and to meet the obligation I felt to document the stand off.

As a young journalist fresh out of college, I covered the Democracy Spring movement, protesting Citizens United in Washington D.C., where 1400 people were arrested. I covered protests outside the Democratic National Convention, including a three-mile march down Broad Street to FDR Park. In fact, these are events I very much enjoy reporting on. I believe that protesting is a cornerstone of democracy.

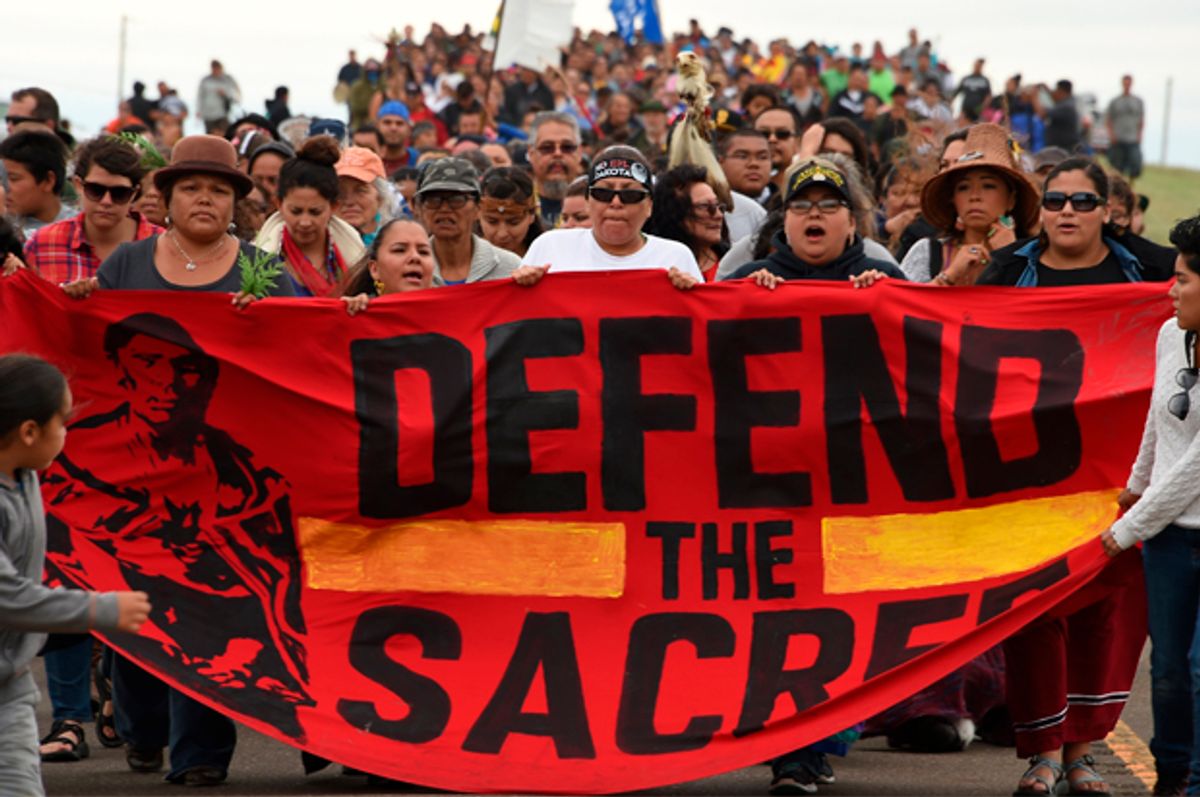

This event was very different. This was not a protest. People from all over the country joining together to not only defend the land that belongs to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, according to the treaties of Fort Laramie in 1851 and 1868, but also to defend the purity of the Missouri river that 18 million Americans use as a source of drinking water.

I was operating on a very tight budget. In terms of my tech equipment, I made use of what I had, bringing my mother's ten-year-old canon 3od camera, a GoPro Hero 3, my notebook, my laptop and a few portable phone chargers.

I flew out of Newark Airport on a clear Friday morning. On the plane, I flipped through "Manufacturing Consent" by Noam Chomsky. It set the scene for Standing Rock perfectly: The civil dissent took place while a corporatized media busied itself pursuing ratings and seeking profit, ginning up endless stories of Donald Trump, and then laying blame for the outcome of the presidential election on anybody and anything the pundits could conjure.

I landed in Bismark and rented a car for the 55 minute trip to my hotel in Cannon Ball, North Dakota. I had never seen such dark roads in my life. About 12 miles from my destination, there was a roadblock. The main highway from Bismarck to Cannon Ball was closed, expressly to discourage people from traveling from to the protest. So I turned down the narrow road my navigation system diverted me to, but I came to a couple of dead ends.

The small road was a sheet of ice, untouched by plow. While making a K-turn to head back towards the main highway, my car slid into a snowbank. As I slid, I was overcome by regret, asking myself: “What was I thinking coming all the the way out here? Why did I think that I would be able to do something about this stupid pipeline? Why didn’t I just choose a normal career?”

I maneuvered lamely for half an hour but only made the situation worse. I was running out of ideas. To my surprise, an SUV pulled down the road. I tapped my brakes rapidly to draw attention to myself. The driver who stopped to offer his full assistance became someone I am still very thankful to have met.

The man who stepped out of the car was Tony Hill, a Navy veteran who served eight years as an aviations electrician. We were both headed to the same place, and for similar reasons. Tony is a bit shorter than I, with very short hair. He was properly dressed for the North Dakota weather, friendly and surprisingly talkative for someone I had just met. He had snacks, supplies and cases of water in his trunk. He looked prepared; he looked like a veteran. And there I was — a kid still in his New Jersey who could tell you more about counterterrorism strategies in Afghanistan than anything regarding a motor vehicle, and who was very confused as to why North Dakotans don’t believe in street lights.

Tony certainly didn’t talk like any of the veterans that I knew from home, who generally (and justifiably) refrain from political discussion. He cared deeply about climate change and he talked at length about the topic. I was pleased to have his companionship and encouraged by his conversation. By the time we got the rental back on the road, we were friends. We agreed to travel together to the protest the next morning.

Oceti Sakowin, the protest camp of the Standing Rock Sioux, was one of the most beautiful places I had ever seen. I admired those who had been camping outside, and their decision to give up the simple privileges we take for granted each day. The tents, teepees and overall wilderness lifestyle were both fascinating and foreign to me. It was much larger than I could have imagined.

Tony went to meet up with some fellow veterans and help them build their camp (because that’s the type of guy Tony is) and I went to get my media credentials. While in line I met a number of journalists, photographers, filmmakers and freelancers, mainly from smaller media outlets. I wanted to gather information from them and to understand why they decided to come out here and what they planned on documenting.

For the first time ever, I felt like a real journalist — as if I was finally put myself in a position where I could do honest work. I spent the rest of the day chatting with locals, veterans and travelers who came from all over the country to stand in solidarity.

I walked up a hill just outside of the camp to get some shots of the closed and barricaded highway. The police, who looked like an army, loomed in the distance in armored vehicles and trucks. I was able to take some useful photographs and then made my way down the hill to Blackwater Bridge, walking to the furthest point we were allowed. A tribe member on horse stormed past the rope and came to an abrupt halt. He stared into the distance at the occupying force, as if he was sending some sort of message to them. There was something very eerie about it, something anachronistic to witness in the year 2016.

The atmosphere of Oceti Sakowin was one of peace and love. The camp was inhabited by people from all over the country who might otherwise never have crossed paths but who stood in solidarity for one common goal. It was the most beautiful thing I have ever witnessed.

On Monday morning, I attended an informal press conference for veterans that included speakers like Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard and Phyllis Young, tribal elder and prominent leader of the movement. They thanked the veterans for their support, and discussed the importance of unity. “Unless we protect our water, there is no economy; there are no jobs; there is no life,” Gabbard said.

I took some time to talk to a few veterans. Their courage and dedication to continued service of their nation's best interests was inspiring. I realized at that moment how much their presence meant to the Natives, to activists and to the movement in its entirety.

“Over and over, there have been plenty of examples of how militarized force does not provide a lasting solution to problems," Jonathan Engle, a former Green Beret, told me. "So it’s energizing, and it restores my faith in humanity to a degree, to see people from all walks of life, all backgrounds, all races, come together and unify in solidarity and just express the spirit of humanity and peacefulness.”

Seeing veterans travel far and wide to protect and stand in solidarity with the Native Americans and their supporters was awe inspiring. This type of event is often considered a “leftist movement.” Drawing attention and assistance from military veterans is a major part of what has made Standing Rock so unique, and ultimately why I think it will succeed.

Later that afternoon, back at Camp Oceti Sakowin, I was anticipating a veteran’s walk to the barrier set up by the police force on Blackwater Bridge. I saw Dr. Cornel West greeting protectors, natives and veterans with hugs and kind words. There was a large crowd and a strong spirit of confidence in the air. Protectors joined hands and encircled the entire camp. Minutes later, a Native came to announce that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had denied the final pipeline permit and construction would be halted. As word spread, so did joy and a sense of accomplishment. Everyone knew the fight wasn’t finished, but it was a serious step toward total victory.

On Monday morning, I attended a ceremony in the casino I was staying at. It was a meeting between some of the military veterans and tribal members of the Standing Rock Sioux. Many of the elders, including Phyllis Young, Chief Leonard Crow Dog and others spoke before the crowd. They reminded everyone that there was still a fight ahead and that they must remain organized and peaceful, even if ETP defied orders and continued to drill. Afterwards, Wes Clark, Jr., one of the primary leaders of the veterans' movement, got in formation by rank, with his men and women behind him. He spoke softly, humbly asked for forgiveness for the long brutal history our country has with the Natives, and offered his service. Watching this moment live was surreal, and I’ll admit I had difficulty remaining composed and professional.

The ceremony ended with the two groups hugging one another, while some veterans shared their stories and explained why they have come to contribute to this cause.

I hoped to head back to camp by the middle of the afternoon, but a blizzard prevented anybody from leaving. It was a hectic 24 hours, in which construction was halted but ETP vowed to continue the pipeline. I thought it might be important to try to get more reactions and thoughts from people around camp, but the storm kept everyone hunkered down inside.

My time in North Dakota was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I learned more about the Dakota Access Pipeline, but also grasped that it wasn’t simply about a oil-carrying pipe in the ground. This issue is about the rights of indigenous people, respecting sacred land and honoring our treaties to Natives. It is about a level of environmental oppression that deserved national coverage.

The story was overlooked as merely the latest chronicle in the tale of the haves and the have-nots. The Standing Rock Sioux encampment was a communitarian living structure: food, shelter and healthcare were shared. I found that what we all agreed on as our shared American values came forward most when they were acknowledged least. Much of what we take for granted is the same thing these people have historically been denied. It’s vital to realize that what the Standing Rock Sioux and their supporters are fighting for is recognition as human beings, and their message has never been anything other than peace and preservation of our planet.

Shares