We're re-running this story as part of a countdown of the year's best personal essays. To read all the entries in the series, click here.

Saturday mornings unsettle me. Especially when the weather’s good. There’s a lively farmers’ market just down the street from us, with a bluegrass band, homemade donuts and vegan tamales. It’s great, if you’re into that sort of thing.

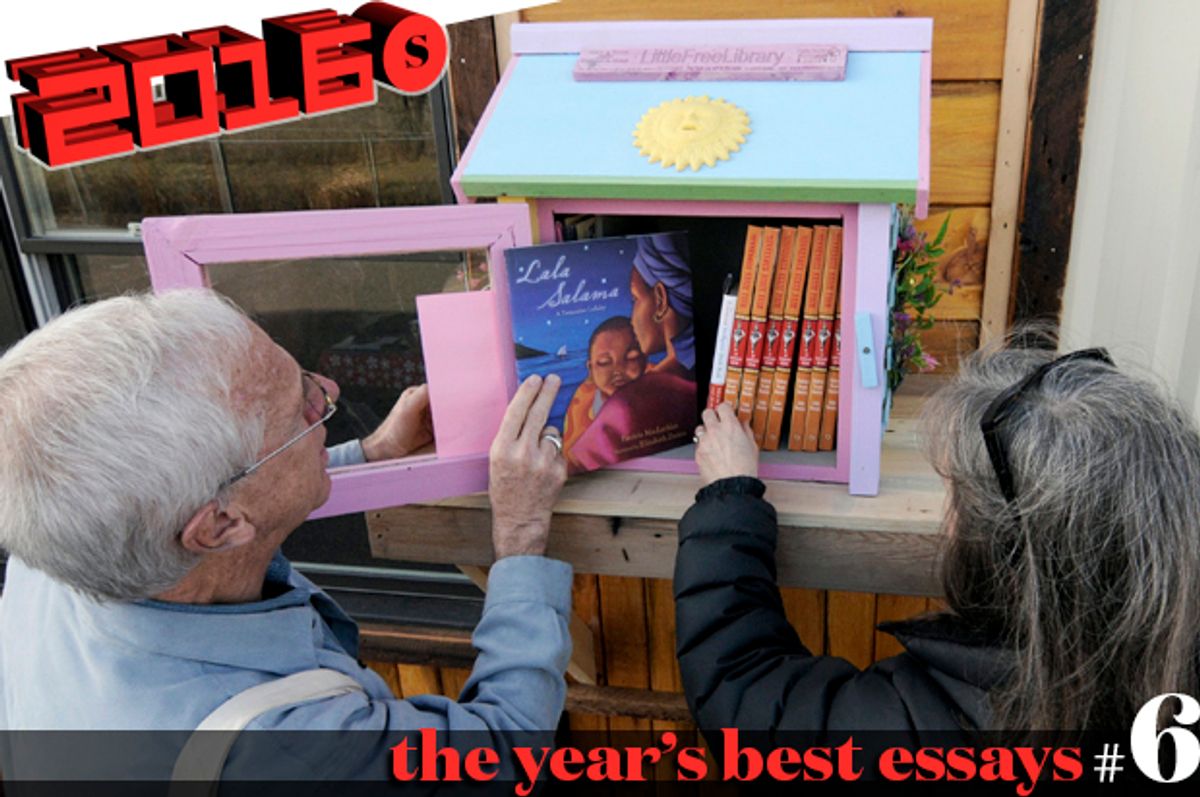

But it means floods of the worst kind of foot traffic. Graying gardeners and aging hippies; Bernie-or-Bust types; millennial parents, tatted and pierced, shepherding toddlers with names like Arya — damn near every one of whom stops to check out my Little Free Library.

And after paying $18 for an heirloom tomato and a pair of zucchini, you can’t blame a person for grabbing a free book. Indeed, this kind of neighborly interaction was exactly what my wife Heidi was hoping for when she got me the library for Hanukkah. Heidi’s the sunny and optimistic type, yin to my cranky yang, which made her an easy mark for the Little Free Library Foundation and its stated mission of promoting “the love of reading and to build a sense of community.”

She and the kids did it up right, painting ours lilac to match the color of our Victorian house. The library makes a striking contrast with the verdant green that blankets our block in the spring. But idyllic as that sounds, when the marketeers, wagons in tow, stop to fiddle with the latch and peer inside, all I feel is dread.

***

Little Free Library originated in Hudson, Wisconsin, in 2009, when Todd Bol built a wooden box with a glass door, modeled on a one-room schoolhouse, in honor of his mother’s career as an educator. He nailed the box to a post in his front yard and stuffed it with books. The idea spread and in 2012 Little Free Library incorporated as a non-profit. By January of 2016, there were at least 36,000 Little Free Libraries across the globe.

They seem particularly popular in our town, Oak Park, a progressive suburb just west of Chicago. We’re a bookish community with a thriving independent bookstore, a showpiece library and a proud literary heritage that includes Edgar Rice Burroughs, Jane Hamilton and Ernest Hemingway.

It’s easy to see why Heidi imagined a Little Free Library would be a great gift for me. I’ve always enjoyed checking out other people’s books. Partly this is a party survival strategy. My misanthropy is such that at social gatherings I like to take a respite from small talk to peruse people’s bookshelves and CD cases, which gives me an excuse to turn my back on literally everybody. Sadly Spotify and Kindle have eliminated most of these analog escape hatches. But I’m still genuinely interested in what other people read. So the idea of curating my own selection was immensely appealing. I’m a history teacher and I dabble as a children’s literature critic, so, if I’m being honest, I flatter myself on my taste in books.

Heidi is even more of a book snob than I am. She’s from the librophile equivalent of old money — her late, beloved father Bill was an antiquarian and her childhood home brims with 18th century atlases and first editions of U.S. Grant’s memoirs. So we both turned up our noses at the castoff books that came bundled and shrink-wrapped with our purchase (an oddly eclectic group which included "Screaming Monkeys: Critiques of Asian American Images" and a set of Disney princess-themed board books). As Heidi put it, in what proved to be a wildly optimistic sentiment, “We’re better than that.”

Since our book collection had long outgrown our shelf space, it was easy to find the first offerings for our library. Our bookshelves, end tables and nightstands were stacked with medium-brow novels, chapter books that our kids had outgrown and, my guilty pleasure, Nordic-noir fiction.

I quickly took to the daily ritual of inventorying our stock to see what had gone into circulation. It was fun to see what sorts of title moved and which got passed over. But as the stacks on the nightstand shrank, a realization dawned on me. We were gonna run out of books. The math was daunting. Even before the spring strolling season had begun, we were losing two to three books a day. With warmer weather and the farmers’ market ahead of us, we could expect to bleed a thousand books a year.

***

Little Free Library has a seductive marketing slogan that’s carved into the top of every unit: “Take a Book; Return a Book.” Such a simple equation. And such wishful thinking. Take? Oh, absolutely. People are, in fact, really good at that part. For example there was the young mom who lifted her toddler up to the box, watching uncritically as he scooped up "Imaginary Homelands," Salman Rushdie’s collection of criticism and essays. Which I’m sure he enjoyed.

When it comes to returning, people mean well. For example, I don’t doubt the sincerity of that young mom when she told her greedy little urchin, “We have to remember to come back soon and give them some books.” The problem is that, to borrow my favorite report card phrase, remembering, for most people, “remains an area of growth.” It’s not that I blame my (mooching) neighbors. Indeed, I, myself, seldom return books to the public library on time. And they fine you if you don’t. But since I don’t punish people (unless you count silent, withering judgment), I’ve got no leverage. The truth is laziness is just part of human nature. It’s what separates us from the beavers.

But the lesson was clear. I wasn’t running a library. Libraries are built around the idea of circulation. And circulation implies a circle. What I had, aside from the contributions of a few kind neighbors on my block, was a one-way street of literary handouts. So it wasn’t long before I concluded that if I was going to stay in business, I had to reduce the outgoing volume.

Luckily I had an ace in the hole. At last year’s public library book sale, our family had, as a joke, played a game of “Find the Boringest Book.” And, not to brag, but we’d kicked some ass.

So imagine my surprise when, within 24 hours, a paper-bound copy of "Study Guide and Reference Material for Commercial Radio Operator's’ Examination" (1955! edition) had vanished. 1965’s evergreen "Technical Analysis of Stock Trends" was next. "Aircraft Power Plants from Northrop Aeronautical" lasted just a few more days. And the winner of our boringest book contest? "Standard Mathematical Tables," 22nd Edition, a nearly wordless and entirely incomprehensible collection of graphs, made it a week.

Okay, neighbors, I thought. You gonna troll me? Come correct.

Out with the Chabons, the Franzens and the Morrisons. Goodbye to the Booker and Pulitzer winners. Ruthless pragmatism became my m.o. Grimly, I took to scouring yard sales and recycling bins for dull books, just another soulless middle manager, firming up his supply chain and moving product.

Now fully in transactional mode, I greeted the news of my teaching partner and good friend James’ decision to move his family to Seattle with this question: “You’re not taking all those books, are you?”

James’ classroom was a treasure trove. He’s a germanophile with a peculiar interest in Prussian maritime history. And he had a class-set of books called "Facts About Germany" (even duller than it sounds). I filled the library with them, 18 in all.

And they went.

As did the German Historical Bulletin’s Supplement 7: “East German Material Culture and the Power of Memory.” The eagerness with which my neighbors absconded with dated monographs about Teutonic history got me wondering what the German word is for resentment of freeloading neighbors.

And it drove home another lesson: Not only was I not a librarian, I wasn’t even really dealing in reading material. That the objects in our Little Free Library happened to be books was beside the point. The salient fact was that the items were free. We may as well, I suspected, have been offering plastic spoons, Allen wrenches and facial tissue. I tested this hypothesis by mixing in non-book items including an instructional DVD on how to use an exercise ball, and a few packets of echinacea seeds.

All of it went.

So why do people take things they don’t need, or even really want? Well, it turns out people really, really like free shit. Daniel Ariely, a psychology professor and behavioral economist, has studied how making things free distorts the decision making process for consumers, pushing us to jettison the traditional cost-benefit analysis we bring to purchases. Think of otherwise sane people showing up late for work because they stood for 45 minutes in line to get a “free” donut.

As Ariely puts it, “decisions about free products differ, in that people… perceive the benefits associated with free products as higher.” I got that quote online from a paper Ariely published with Kristina Shampan’er entitled “Zero as a Special Price: The True Value of Free Products.” I’m sure Ariely wrote something similar in his best-selling book, "Predictably Irrational." But I can’t say for sure because somebody scooped up my copy about an hour after I put it in my Little Free Library.

Shares