Warning: This article contains spoilers.

When Beethoven composed the "Moonlight Sonata" in the summer of 1801 in Hungary, he did it for his young student whom he loved, 17-year-old Countess Giulietta Gucciardi. One of the most popular piano sonatas ever written, the piece has inspired love stories over the ages. Never would Beethoven have imagined that the soft, passionate melody made up of parts — as all sonatas are — would come to mind when thinking of long-unrequited love between men in the Oscar-nominated film "Moonlight."

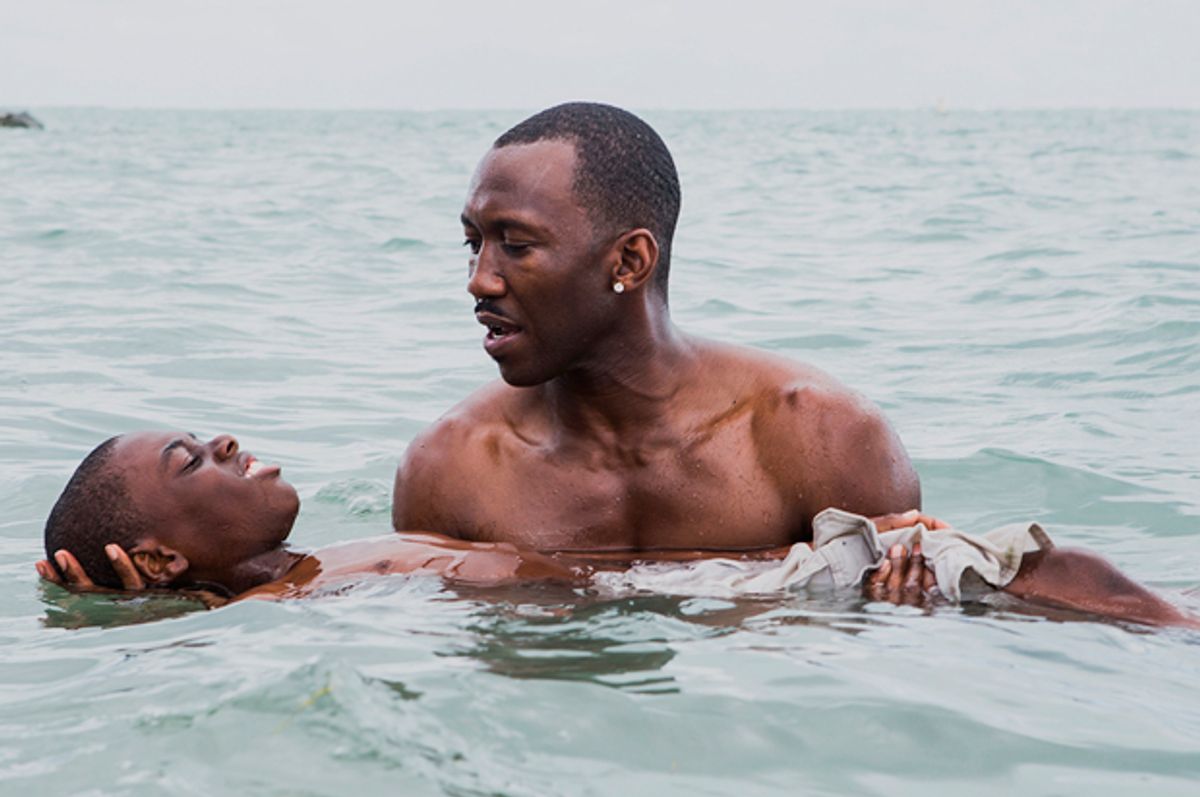

Painted on a rich palette of cultural and socioeconomic issues, the film is divided into thirds by writer-director Barry Jenkins: "Little," "Chiron" and "Black" represent the main character Chiron's experiences growing up poor, black, bullied and gay in Miami. He is a boy who cannot swim in a drug-flooded culture, buoyed by the kindness of strangers.

Mia Mask, an associate professor of film at Vassar College, picked up the phone on the first ring when I called to ask her opinion about the significance of "Moonlight." Would the first mainstream gay love story between men of color — and, at that, the first mainstream movie gay love story between any people of color since 1985's "The Color Purple" — change anything in Hollywood? Does a Best Picture nomination and a Golden Globe win influence the tide of studio green lights in favor of showing diverse and healthy sexual relationships?

"It's definitely a big deal," said Mask. "I’m happy to see 'Moonlight' get the attention it’s getting. It’s wonderful," she added. "I do think it’s significant that a film not only about people of color but also one that highlights a homosexual relationship is nominated for Best Picture."

Mask thought for a bit about historical precedents in film, like how big-budget, mainstream movies such as "Brokeback Mountain" and "Phildelphia," set a precedent. "Finally, if you're a gay character in a major film, "'Moonlight' suggests" that you don't have to have AIDS or be alone," she said. It also bears mentioning that television writes and casts for far more gay characters than film does these days. Many of those cast for roles are people of color, but the overall casting of gay characters in movies remains white.

Either way, these characters are closeted or envisioned as the sidekick, the lost, the complicated friend, the misunderstood — fey or butch and played for laughs. In "The Wedding Banquet," for example, Wai-Tung, a gay Taiwanese immigrant, lives in Manhattan with his boyfriend Simon but agrees to marry a Chinese woman to keep his parents from knowing the truth. Will Smith as Paul in "Six Degrees of Separation" is a con artist: debonair, charming and hiding who he really is. In "Boys on the Side," Whoopi Goldberg is Jane DeLuca, a lesbian singer who has broken up with a girlfriend who's not integral to the story; she takes a road trip with Drew Barrymore to get over it.

When the documentary "The Celluloid Closet" came out in 1995, the public could begin to understand how rare it was for gay or queer or trans characters to be featured in film at all. "Obviously in the avant-garde films of Marlon Riggs [who made 'Tongues Untied'] or Isaac Julian [creator of 'Looking for Langston'], you saw these characters, but in mainstream films for Hollywood, no," Mask said. She cited other films that were more commercially viable and celebrated by the entertainment community —"Rise" and "Paris Is Burning" — but even the star-studded "To Wong Foo! Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar" was filled with camp, comedy and Wesley Snipes, Patrick Swayze and John Leguizamo in drag.

A few older examples preceded "Moonlight" and showcased homosexual relationships between people of color, but they are few and far between. None rose to the level of recognition by the academy that "Moonlight" has attained. "Set It Off" (F. Gary Gray, 1996), which starred Queen Latifah, and "Pariah" (Dee Rees, 2011), were big indie hits. "Moonlight" has ascended, and perhaps that is about timing and the gritty sweetness amid horrible life circumstances that the main character eventually experiences. The characters, too, are very subtly gay, and the film could be called "arty" (for example, tilted camera angles, blurred frames pulled into focus, close-ups and the natural sound of a bell as a restaurant door opens, ), so perhaps this is why it has worked its way into the hearts and minds of the Academy.

And it must be said that we've come a long way since the Motion Picture Production Code of the early 20th century, which lasted well into the 1960s. The production code or the Hays Code, was the set of industry moral guidelines that U.S. films had to follow in studio release. Beginning in 1930, Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America from 1922 to 1945, adopted puritanical rules about content that filmmakers had to abide by. Even on-screen kisses between heterosexuals were limited to three seconds.

Like "Set It Off" and "Pariah," Mask pointed out, "Moonlight" "represents efforts by filmmakers to enrich and complicate the representation of American life by featuring queer characters of color," said Mask. Unlike "Moonlight," in which Chiron is beaten for not fitting in (largely because he is studious, quiet and suspected to be gay), the other two films represent homosexual characters in love without judgment.

Said Mask: "In 'Set It Off' and 'Pariah,' the gay relationships are not pathologized as unhealthy or aberrant but are part of natural, normative desire. In both movies, its clear that the social context — not the identities — is what needs to change."

Will "Moonlight" really change the way Hollywood does business? Mask said no. "If you look at 'Brokeback Mountain,' it should have normalized things, but it didn’t. The majority of films that are green-lit are very commercial, and 'Moonlight' feels like an indie. So it will be treated that way by the academy," said Mask. "It might win screenwriting but not Best Picture."

Still, the film represents progress. Mask said she believes films like "Moonlight" signal an important message to moviemakers, which can foster change. "It does send a sign of positive reinforcement to the filmmaking community that these films will be acknowledged."

Shares