As Fashion Week came to a close in New York on Wednesday, there were a few new designers showing just under the wire, and they weren't run of the mill ready-to-wear people, either. Some of their designs, like a pair of stiletto boots with designs beaded over a Christian Louboutin base, were part of the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian's "Native Fashion Now" traveling exhibition, which opened yesterday in New York at the George Gustav Heye Center.

“Native Fashion Now,” which debuted at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, last year and runs in New York through Sept. 4, is the first large-scale traveling exhibition of contemporary Native American fashion. Celebrating indigenous designers from across the United States and Canada from the 1950s to today, the exhibit looks at the interstices of fashion, art, cultural identity, politics and commerce.

More than 60 works showcase the art of Native fashion designers and artists, such as mid-20th-century pioneer Charles Loloma (Hopi Pueblo) as well as contemporary designers Wendy Red Star (Apsálooke [Crow]), Jared Yazzie (Diné [Navajo]), Jamie Okuma (Luiseño/Shoshone-Bannock) and Sho Sho Esquiro (Kaska Dena/Cree).

“New York City is a fashion capital of the world and the works shown in this exhibition belong on this stage,” wrote Kevin Gover (Pawnee), director of the National Museum of the American Indian, in a press release. “Native voice is powerful and Native couture is a megaphone. These designers’ works demonstrate to visitors the contemporary strength of Native iconographies and sensibilities.”

High fashion, high art

Those beaded stiletto boots, designed by Jamie Okuma, took many months to create by hand. Sure, Louboutin's design house can do elaborate handmade designs too, but unlike Okuma, it has many hands to help do the work. For Native American designers like Okuma, the work can only be done by one, because the designers are guided by sacred cultural symbols unique to their heritage. Okuma's work can be seen in the permanent collections of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Nelson-Atkins Museum, the Peabody Museum and the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, and she is one of a growing number of Native American designers quietly working their way into mainstream fashion, often using art as a dual method of gaining attention and traction.

Like Okuma, Cree and Kaska Dena Nation member Sho Sho Esquiro, of the northern Athabaskan tribes, grew up watching her mother sew, and learned to do everything by hand.

"We sewed hats, gloves, moccasins; growing up in such a remote area, where there wasn't much to do, it was a pastime for me as a kid," Esquiro said.

She can remember first sewing when she was around 5 or 6, making outfits for her Barbies. Later, Esquiro became aware that clothing styles could go in or out of fashion, so she had to find her own niche. "I wanted my fashion to also be looked at as art, so it would be relevant in museums," Esquiro said.

Many Native designers use traditional materials and patterns to set themselves apart, but they don't always. "I don’t necessarily have to be beading or using feathers, but it's always made clear that my work is created by a Native woman," said Esquiro. "I also like to use materials that maybe my people would have used, but perhaps not if they didn't have them. For example, I’ll use beaver tail, even though it wasn’t something traditional for our people, because they didn’t have access to it."

In 2014, Esquiro showed at New York Fashion Week at the New Yorker Hotel as part of Fashion Week’s couture program. This show led to another show at the Eiffel Tower in Paris the following year. "My mom always told me to make sure you’re doing your best week, because you never know where it is going to end up, and I know I am lucky to be showcased in such an amazing museum today," she said. "It was a life goal for me."

She said she believes the industry is seeing a trend in Native American fashion, and is seeking out Native designers. "It’s a really exciting time for Native designers," said Esquiro. "This exhibition will open up many other doors, and we should all work hard.”

"This is a stolen piece"

Native American people have been fighting an uphill battle against big brands like Urban Outfitters and Forever 21, which have taken important and culturally significant tribal designs and incorporated them into lines without permission. The Native Americans argue (and I would say, correctly) that certain images and designs are sacred to a family, and are in fact family/tribal identifiers. Thus, they should not be treated as trends, nor should they be put up for sale.

Then there is the legal matter of unlawful appropriation. The Indian Arts and Crafts Act states that “it is unlawful to offer or display for sale or sell any good . . . in a manner that falsely suggests it is Indian produced, an Indian product, or the product of a particular Indian or Indian Tribe . . . within the United States.”

From mass retailers to couture lines, “Native” fashion elements — such as suede fringe, beading and tribal patterns belonging to specific families — are being used without permission, attribution or any benefit to actual Native American designers. In 2015, an Inuit Nunavut family was furious to learn that a high-end European clothing designer, Kokon To Zai, was selling a beaded, embroidered sweater with a copied design originally created as a sacred, spiritual protection for Ava, an Inuit shaman. The family had images to prove the theft, and as Salome Awa, great-granddaughter of the shaman, told CBC Radio at the time, “This is a stolen piece. There is no way that this fashion designer could have thought of this exact duplicate by himself.”

As Urban Outfitters also learned in recent years, violating the IACA can mean serious business. Fines up to $250,000, or a five-year prison sentence for individuals, can be levied, and businesses can be charged up to $1 million. Urban Outfitters was sued by the Navajo Nation in 2012 for using Navajo designs without permission, and that lawsuit was not settled until November 2016. Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye said at the time in a press release that the tribe expects companies to seek permission when considering using the Navajo name, design or motifs. "We believe in protecting our nation, our artisans, designs, prayers and way of life.”

Urban Outfitters offered a mea culpa, and also noted that the tribe and company had agreed to partner up in offering official Navajo jewelry in the near future. "As a company, Urban Outfitters has long been inspired by the style of Navajo and other American Indian artists and looks forward to the opportunity to work with them on future collaborations," Hayne said in the same release.

Not all Native American designers strictly observe the no-copy rule, and some exercise temperance in certain situations. "I’m not one of those people who feel like other designers shouldn’t take anything from our culture, because I am inspired by other cultures myself," said Sho Sho Esquiro. "However, there are some things of our culture like headdresses that are sacred and shouldn't be used, and there are instances where big companies have copied someone’s family crest — just like Scottish tartans belong to certain families."

Streetwear that belongs in a museum

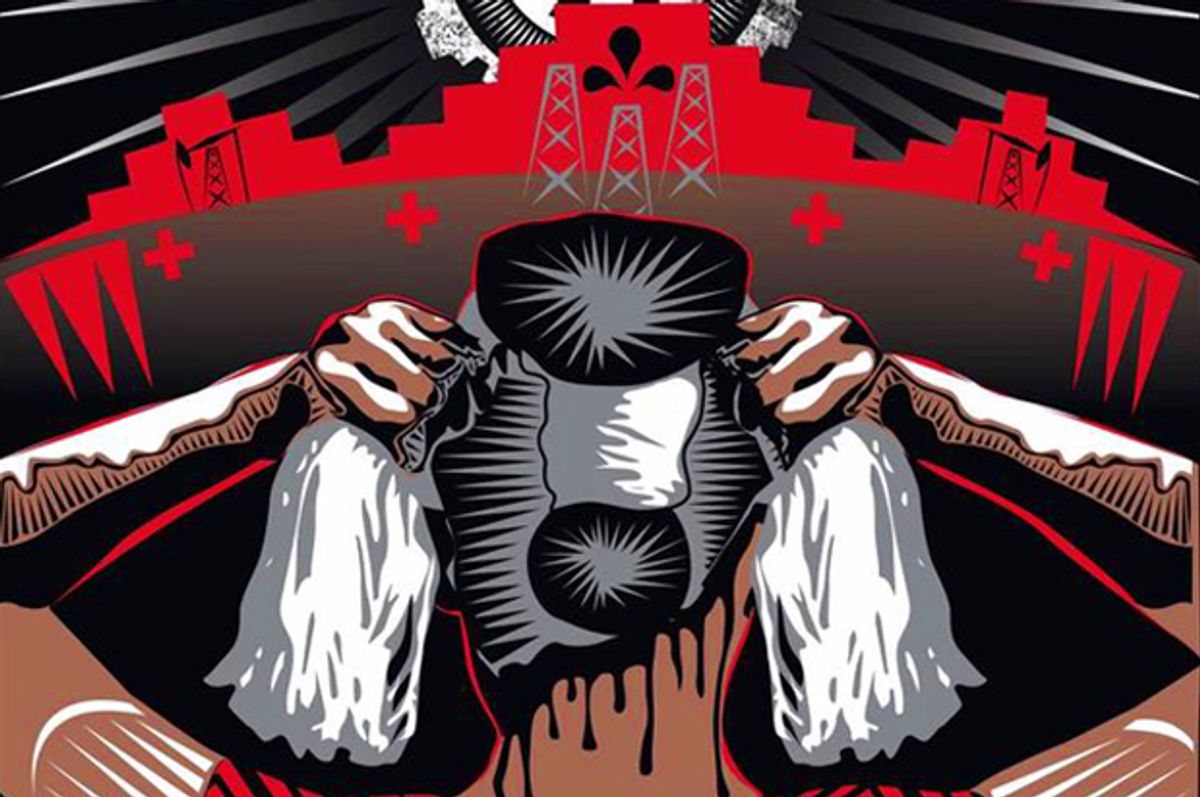

The designs of Jared Yazzie, founder of OxDx (“Overdose Designs”), are also featured in “Native Fashion Now.” Based out of Chandler, Arizona, OxDx produces street wear incorporating images depicting American Indian struggles, issues and art. As such, Yazzie's work is strongly influenced by Native American culture, street art and music, and is designed to be accessible and affordable.

Yazzie said in a phone interview Friday that he sees fashion as a way for Native American people to convey political messages, and positively reshape traditional, racist images of Native Americans to positively influence young people.

“If I have a means of making a statement in any way possible, fashion seems to be the most provocative way,” Yazzie said. “We as Native people have always used what’s around us to survive, and in the modern world, what’s around us now is social media."

One of Yazzie’s most provocative and popular designs is an image of the Cleveland Indian mascot, Chief Wahoo, which he morphed into the skull logo of the Misfits, an American horror punk band.

Yazzie first studied engineering on scholarship at the University of Arizona, but while in school he realized art and design were his passions. Meeting street artist Shepard Fairey was a turning point for him, and he started designing hand-painted t-shirts on the side. People bought them, and he soon dropped out and began training in screen-printing, editing and design. He’s been creating street wear for a year now, and has plans for a fall 2017 line of skirts and dresses, as well as the creation of a safe work space in Arizona near his reservation where designers and artists can come to learn and work. “I want to bring in artists to help and teach the kids, because I never had anything like that when I was coming up,” he said.

Recently, Yazzie said he was proud to announce that the National Museum of the American Indian had commissioned an anti-DAPL (Dakota Access Pipeline) piece, which it would sell in conjunction with the final stop of “Native Fashion Now.”

As he stood in the gift shop at NMAI Friday morning, Yazzie said he was proud to see his work displayed on mugs, pins, bags, shirts and more. “I wanted to depict the impact the land has on us as Native people,” he said. “We live by it and die by it. The earth is our mother, and when she is in pain, we are in pain.”

Explaining the image of his that the Smithsonian bought, he wrote on Instagram, “The woman overlooking the land is Diné, and prepares herself for the fight ahead, tying her hair in a tsiiyéeł (traditional Navajo bun).”

Yazzie says the Smithsonian exhibit and Fashion Week are a jumping-off point for growing his brand. “I’m building the base to go out and do trade shows, places where I can be seen by buyers,” he said. “I want to come correct, and know the best way to approach the business, so I’m doing a lot of research.”

As for his goals in the product he creates, Yazzie said he's trying to create "a better outlook for Native people."

"The Washington Redskins still have the Redskins name, and it’s dehumanizing for the youth," he said. "The high suicides on the reservation are untenable, and it’s because kids don’t have a positive self- image. I am trying to pave the way for future generations, because I know they are going to come with some strong art.”

Shares