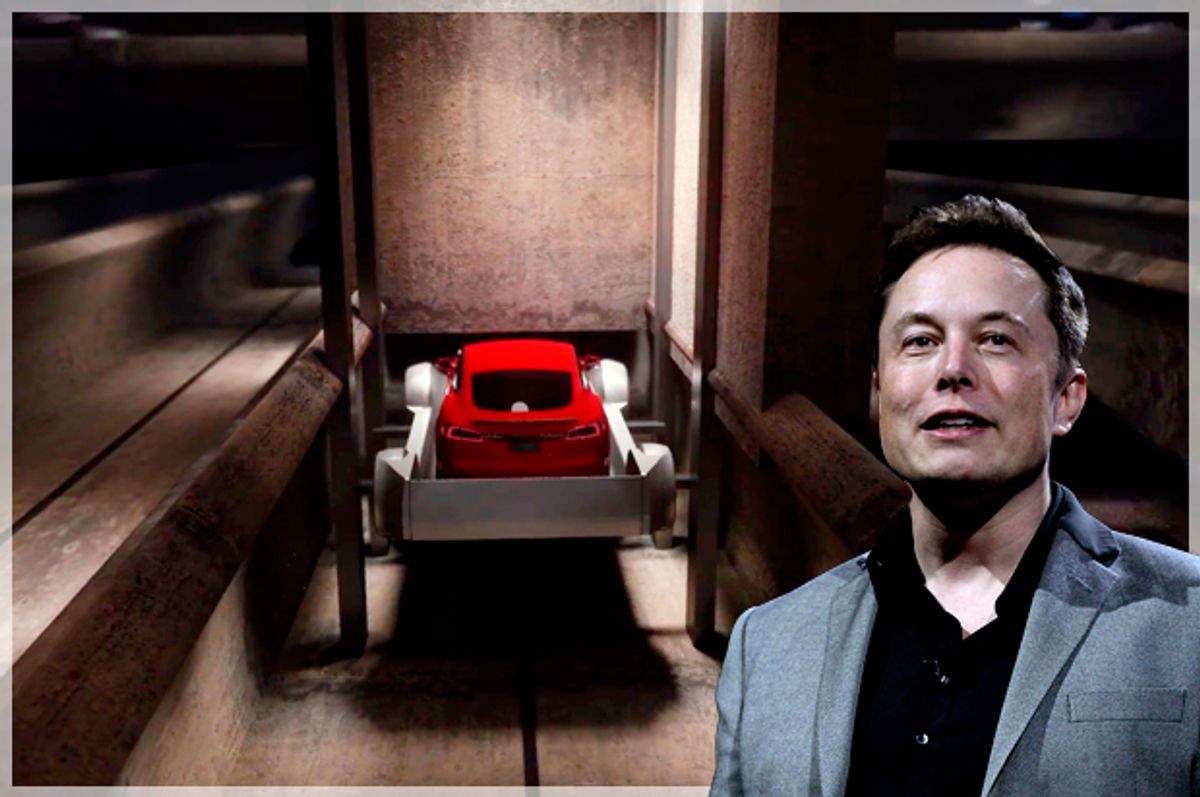

Elon Musk revealed recently more details about his proposal to solve traffic gridlock by creating an elaborate 3D matrix of subterranean highways that would whisk cars around on electrified pallets.

But aside from obvious questions about technical feasibility and the cost to build and maintain such a network, some urban planners are questioning whether increasing the capacity to accommodate more individually owned vehicles is the best idea for resolving traffic congestion.

To some, Musk’s idea seems less like a future-of-mobility vision and more like a throwback to the past when city planners focused on building out passenger-car capacity by lacing together a network of roads and highways, which played a major role in suburban sprawl and snarled urban traffic.

[jwplayer file="http://media.salon.com/2017/05/dfa6ecf7658c458851dd8a6382c24381.mp4" image="http://media.salon.com/2017/05/689948aacdad80eb8232f1b35e4f12ed-1280x720.png"][/jwplayer]

“It’s been shown many times that when you increase capacity over time you reach capacity and it doesn’t solve your problem, unless you address the real problem of having too many car trips,” Kaan Özbay, a professor at New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress who studies large scale complex transportation systems, told Salon. “Using smart strategies is much cheaper and much more feasible.”

The reason why traffic expands to meet the space that’s provided for it boils down to natural human selfishness, which — as anyone who drives knows — gets worse when people get behind the wheel.

A phenomenon known as Braess’ paradox, named after a German mathematician who studied traffic equilibrium in the late 1960s, has shown time and again that drivers will gravitate to routes that they consider most favorable. In a nutshell: Adding more ways for people to move around in single-passenger vehicles doesn’t solve traffic congestion, and in some cases can make it worse by providing more opportunities for people to take trips they wouldn’t have otherwise taken.

Of course, Musk doesn't see it this way and, true to his nature, he’s putting his own money and effort behind his tunnel vision. (Considering Musk’s bold plan to send people to Mars, developing new boring technology might actually be part of Musk’s space-colonization synergy. Building underground habitats on Mars or the Moon would protect interplanetary residents from the harmful ionizing radiation people on Earth are protected from by the atmosphere.)

In December, Musk founded The Boring Company, an infrastructure and tunneling startup that wants to design a better, faster way to tunnel through soil and rock. Earlier this year workers began digging a test trench at the SpaceX facility in Los Angeles.

Musk’s Rube Goldberg-esque system, depicted in a CGI animation published at the Boring Company’s YouTube channel on Saturday, entails an elaborate system of automated street-level elevators. The video depicts a dedicated street-level lane where cars roll onto pallets and descend into the tunnel. The cars then remain on their pallet, which speeds forward on a single-rail electric skate.

The Tesla Motors CEO says this would turn a roughly two-dimensional driving space (roads laid on a surface) into a three-dimensional multilayered underground matrix of tunnels that would offer limitless road capacity expansion. Picture an ant farm where most of the ants are scurrying around in their tunnels rather than the surface, and you get the idea.

“The deepest mines are much deeper than the tallest buildings are tall, so you can alleviate any arbitrary level of open congestion with a 3D tunnel network,” Musk said during a recent TED Talk discussing his tunneling project.

Musk has expressed interest in building first a tunnel from SpaceX headquarters to the Los Angeles International Airport, a distance of about three miles in a straight line. The project would require a lot of paperwork and city council approval. The tunnel would have to bore its way around an underground network of sewage, drainage and power lines, further adding to the technical challenge.

While all of this is feasible, even for an earthquake-prone city like Los Angeles, it’s also expensive. In 2014, the state of California completed a fourth bore to its Caldecott Tunnel, which helps to smooth traffic on the crowded State Highway 24 between Oakland and Orinda. The system of parallel traffic tunnels cut through a mountain has served drivers for 80 years, but the recently completed fourth tunnel, which is just 3,389 feet long, took 14 years to build from its planning stage at a cost of $402 million, according to state figures.

Cost and schedule overruns are also common issues in major infrastructure projects. Bent Flyvbjerg, a professor at Oxford University’s Saïd Business School who studies the planning and management of major infrastructure projects, estimates that major bridge and tunnel projects tend to cost nearly a third more than expected and take about 20 percent longer to complete than initially expected.

Musk says the key to his plan is lowering construction costs, and he’s proposed a 50 percent savings by using machinery that can simultaneously bore and construct the concrete tunnel wall. Those processes are usually done separately. It’s that kind of thinking that some urban planners say will help innovate infrastructure development.

“I wouldn’t just laugh [Musk’s proposal] off,” Flyvbjerg told Bloomberg in February. “The construction industry really needs disruption,” he added. “It’s the only sector of the economy that hasn’t improved its productivity in the last 50 years.”

But for urban planners like Özbay, the bigger question is whether this is the most efficient way to tackle traffic congestion.

Most gridlock occurs at the so-called “last mile” of a trip, he said. Traffic on an interstate highway usually flows freely, but the problems occur after cars leave the off ramp and pile onto local avenues, where traffic moves slower. Boring a matrix of tunnels to avoid urban traffic congestion won’t resolve issues at the entry and exit points of the network. Imagine drivers lining up waiting for their turn to drive onto one tunnel pallet at a time, or being stuck in gridlock at street level after exiting the system.

A better, smarter solution, says Özbay, is so-called Transit Oriented Development, an increasingly popular city-planning strategy that tackles the fundamental problems of congestion: the cars themselves. Establishing strategies that reduce household driving, increase public transit ridership and expand mobility choices would cost less and provide better long-term solutions. And it seems to be the direction cities and ride-sharing startups are taking by encouraging people to ditch their cars and embrace public transportation and ride-sharing services.

“I’m not saying something like [Musk’s proposal] isn’t feasible, but there are some big challenges,” Özbay said. “And building more roads is not always the best solution.”

Shares