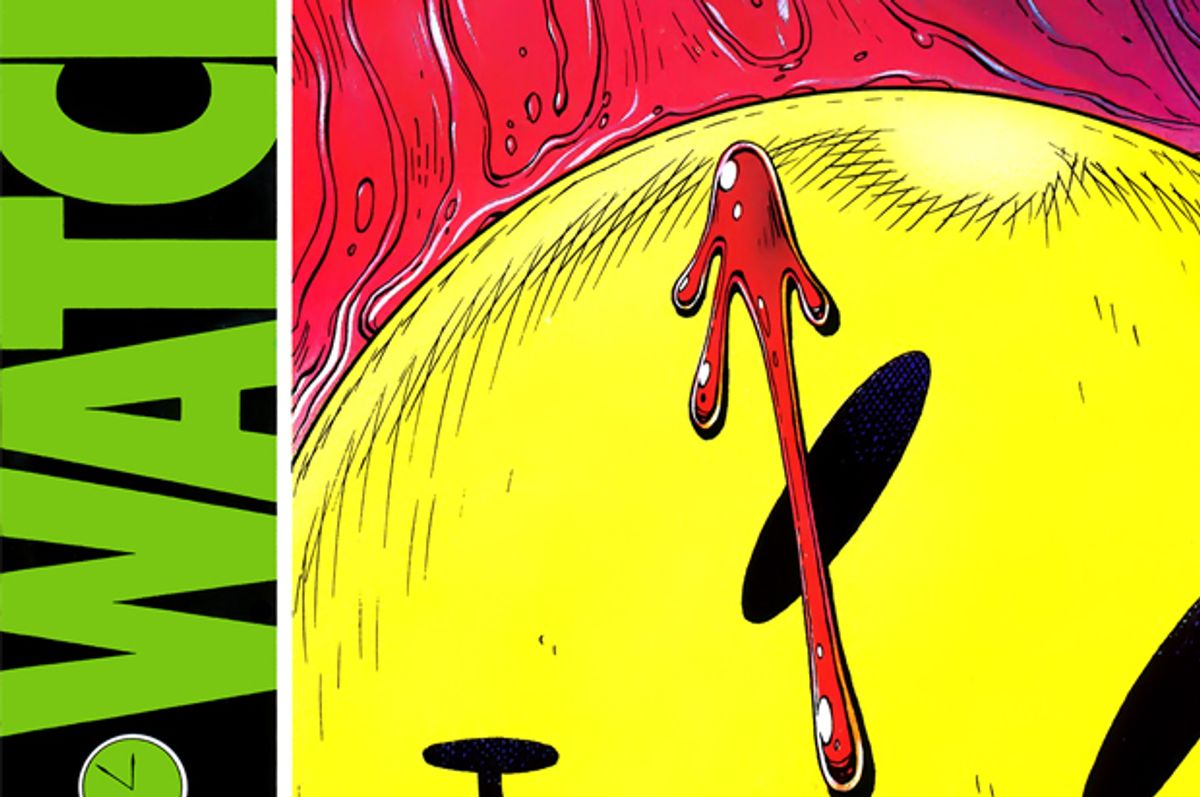

News broke on Wednesday that HBO, the channel that gave us "Game of Thrones," and Damon Lindelof, the creator behind "Lost" and "The Leftovers," are in development on a new miniseries adaptation of writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons' seminal, groundbreaking 1986-87 comic-book series "Watchmen."

Perhaps we would be better off if it never came to be.

It's true that reports of the partnership — an HBO version of the work had long been rumored — were met with cautious optimism. After all, the work that many have cited as the best comic book ever produced, one that had suffered a disappointing, overheated big-screen adaptation in 2009, landing in the hands of the platinum premium-cable outlet and the producer of the most thoughtful (if dour) scifi shows in memory, would seem to be a good sign.

Certainly, those who know and love the comic would agree that, if any live-action version of "Watchmen" were to follow director Zack Snyder's misbegotten, off-tone big-screen translation of Moore's work (which our initial reviewer happened to love, as is his right), a miniseries would be the best format and HBO would be the best home for that miniseries.

As well, while Lindelof's work on "Lost," two of the last three "Star Trek" films and "Cowboys & Aliens" lacks heft, direction and resonance, his production of three seasons of HBO's "The Leftovers" shows a remarkable thoughtfulness and, if nothing else, a particular and interesting internal consistency. Moreover, you couldn't say his writing on the half-cocked "Prometheus" lacked ambition.

It's, on paper, a good lineup that could only be made stronger by strong casting (an HBO speciality), solid production values (ditto) and a good slate of episode directors (again, another of the network's many virtues). If one had to transfer "Watchman" from the page to the live-action screen while preserving a decent amount of the text's value, this is a better setup than most would be.

Still, given the yawning width and depth of the original text, even approaching such a translation seems a gamble perhaps better left untaken. The examples of why it's perhaps best to leave "Watchmen" as is are too many to cover here, but five easy ones jump out.

First, not only is "Watchman" a knotted, troubling narrative populated by knotted, troubled characters that would require any cast or creators to be at their best, it is itself multi-platormed and, in a sense, metatextual. Extensive newspaper clippings, book excerpts and, notably, another comic book — all of them hailing from Moore's fictional world — appear throughout the "Watchmen" issues. They are essential rather than peripheral parts of the "Watchmen" story and experience.

While Snyder incorporated at least some of those elements into his 2009 retelling, the work was slapdash and, true to the director's style, mined for bombast instead of meaning. Interestingly, the failure of their partial inclusion leads one to question whether any live-action version of the work could employ them in an episodic format.

It's easy to imagine Lindelof will try where Snyder failed. It's harder to imagine how newspaper clippings will play out on screen (the gambits attempted in the live-screen adaptations of similar works such as "The English Patient" and "Cloud Atlas" were ultimately less than satisfactory).

Other elements of the text might present issues as well. From the careful placement of near-hidden symbols, nods and characters in its thousands of images, to the many effects of its famous nine-panel page format, so much of what made "Watchmen" succeed was not only the dialogue and script provided by Moore, but the stark, brilliant art of Gibbons. Snyder's dark, neon-flecked baroque cinematography and "Matrix"-inspired shot selection jettisoned this core part of the text. It's unclear how any director or cinematographer could preserve it or replace its profound value. Live action just doesn't work that way.

There are other visual issues. These characters — some of them out of shape, some of them impossible Adonises — were meant to look absurd. From the eerie flat-blue skin of Doctor Manhattan to Nite Owl, a hero who very much looks like he's wearing pajamas, the presentation of these characters underlines the ridiculousness of the idea of superheroes. Snyder covered it up with CGI and "Dark Knight"-style armor, but it's essential. Again, such aesthetics might be a huge viewer turn-off in a live-action setting.

There are pressing political concerns as well. "Watchmen" offers many, many things, but front and center is an informed anarchist critique of politics, culture and the ideal the hero in the post-Vietnam Reagan-Thatcher era. Ironically, given that it was put out by corporate publishing house DC Comics, "Watchmen" is also a scathing anti-corporatist artwork more than likely influenced by Marxist and other revolutionary texts and written by, again, a self-declared anarchist. There are touches of historicism and other philosophical or intellectual stances as well, none of them presented as cuddly or satisfying.

Support for these resonances is yet another point on which the 2009 adaptation failed. Snyder is, by all appearances, a cheerless Randian objectivist, who always puts the wants and desires of his characters above those of the many a la "The Fountainhead" (a work he wishes to adapt). Not only did his anti-altruistic approach turn classic superheroes into petty, selfish children in "Man of Steel" and "Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice," it turned the anti-corporate, anti-capitalist, borderline Marxist "Watchmen" into something it was never meant to be — a particularly enthusiastic (if dark and gritty) example of the sort of superhero theatrics Moore and Gibbons intended to undermine.

HBO and Lindelof are no doubt more nuanced, empathetic and, well, democratic in their visible belief systems. At the end of the day, though, both are very corporate, very capitalistic in their approaches. It seems almost too much to ask that they could support the underlying and, in its finale, somewhat nihilist thrust of this artwork. "The Leftovers" signals Lindelof can hear such threads, but it does not demonstrate he can follow them.

And that reveals a final point. The metatexuality, the complicated politics, the open-ended philosophies and the curious, rare joy and rage flowing through most of Moore's many great works makes them almost above deconstruction. Such thorniness, such stickiness certainly hasn't lent them to translation or adaptation.

Indeed, no live-action retelling of any of his works — from "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen," to "From Hell," to "V for Vendetta" has been actually, truly good. Actually, they're pretty godawful, not just as Moore adaptations, but as movies full stop. Even 2016's animated "The Killing Joke" was a mess.

Only the 2004 "Justice League" episode that adapted Moore's 1984 "Superman" Annual Vol. 1 #11 story "For the Man Who Has Everything" came close to capturing the magic of its original text, and it was a 22-minute daytime cartoon of a 43-page single issue.

This is all to say, yes, the HBO series holds some promise and could surprise much in the way "Westworld" did. This writer will surely be viewing it with the hopes that it not only represents the same value of "Watchmen" and carries a bit of its complicated magic, but upends the live-action superhero genre in the same way that Moore and Gibbons' printed work did 30 years ago. After all, it's a genre in need of upending.

But perhaps it would be even better to let "Watchmen" lie, to appreciate it not as an "intellectual property" of Warner Bros., but as the querulous, engaging complete object it is. Not everything needs to be on screen, and some things are better off it.

Shares