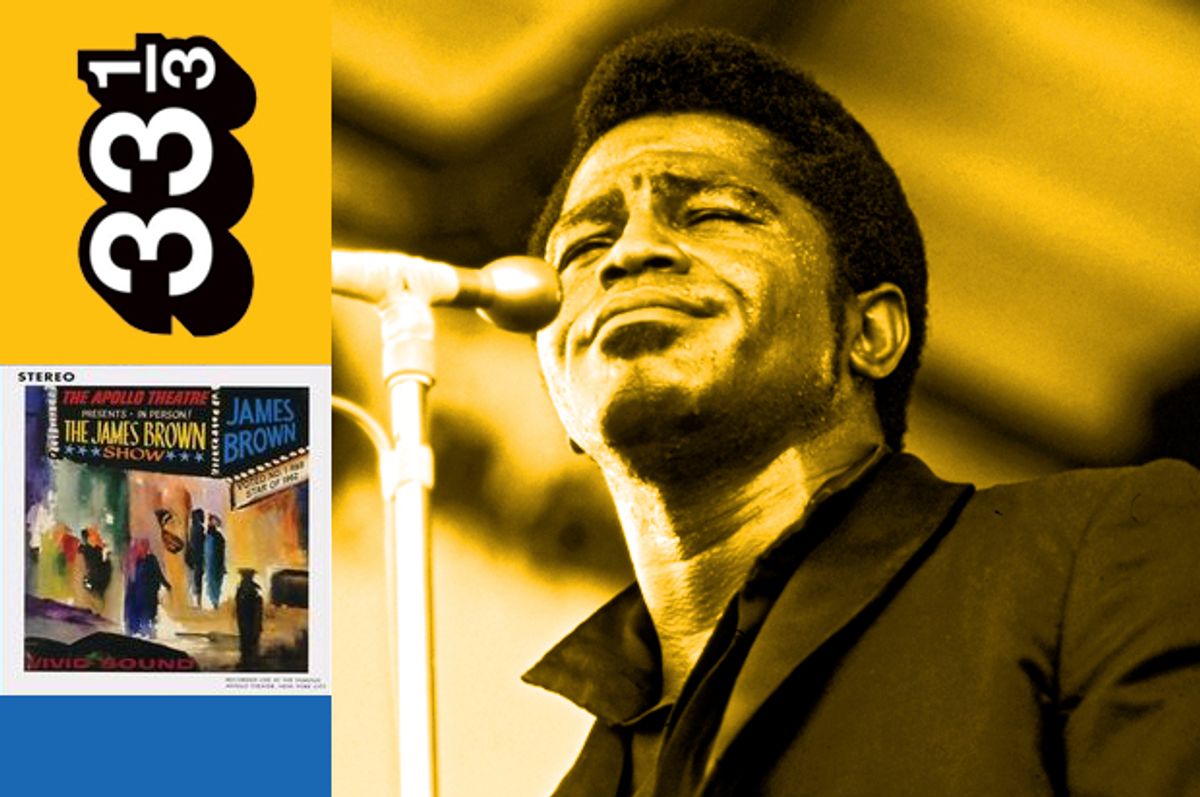

SWEAT

James Brown is already covered with sweat as he dances across the Apollo's stage to the instrumental break of "Think." His face looks like it's wearing a mask, a huge lattice of tiny diamonds, rolling down his face or just falling off and crashing to the floor. His hair, painstakingly styled before each show by Frank McRae from Philadelphia into a gleaming, processed pompadour, is becoming disheveled; little soaking-wet strands of it fall across his face, tufts are sticking up from the slick black mass. He is wincing as he sings and smiling when he doesn't.

JAMES BROWN ON THE TOPIC OF HAIR AND TEETH, IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY

"Hair is the first thing. And teeth are second. Hair and teeth. A man got those two things he's got it all."

THINK

Standing behind him, James Brown's band are playing their arrangement of "Think" as fast as they're capable of getting through it without collapsing (it almost falls apart during the solo). Through most of the song, JB is skimming across the lyrics like a seabird, touching down on them only now and then. He holds off on the first "Think" as long as it's feasible, and then some—almost all the way through the next phrase of the song. Then he jumps free of the rhythm for a moment: " ... about the baaaaad things"—and garbles a few vowels for a moment before he sings something a little bit like the first verse. This song cannot possibly make sense to anyone who hasn't already heard it. He's doing to his own record what the record did to [the original version by] the "5" Royales. That? That was two years ago. Catch up.

(Later in his life, speeding up songs to make them more exciting will become a toxin afflicting James Brown's live shows. "I Got You" and "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag" will turn into thirty-second throwaways; slow, hard funk grooves will be accelerated until they lose their bite. But this one works.)

The Famous Flames just move and clap. They can't possibly keep up with the background vocals, except for the odd snap of "think!" in the chorus. The two drummers are playing so fast their beat almost keeps up with the speed of the organ's oscillations. When the song ends with two bold blue horn clusters, you can imagine the entire band quietly panting. Except for Les Buie, who barely has time to wipe his hands off before he has to start the link.

HOLD IT

Another twelve seconds of "Hold It," another twelve seconds of dancing in radiantly shiny black shoes. (Brown, as he never tires of telling people, was a shoeshine boy as a child, and has kept the impulse ever since: he'd fine his bandmembers if their shoes were scuffed.) The rest of what James Brown was wearing? It's hard to say: he traveled with around 70 tailored suits, which he called his "uniforms." A February 1962 Sepia magazine article featured him showing off his "$50,000 wardrobe" and mentioning that when he did a weeklong engagement in a theater, he'd wear 35 different outfits—a different one for each show.

The band is perfectly groomed, suited-up, in place, hitting cues with near-military precision. If somebody missed a note or played an extra beat, Brown would dance over to them and flash his hand at them—once for five dollars, twice for ten—and dock their pay for that night.

I DON'T MIND

Brown was a disciplinarian, though, not a perfectionist: he had no objection to letting great records go out with bad notes on them. (Check out the guitar solo in the middle of 1971 's "Get Up, Get Into It and Get Involved." It's terrible, but that was the take with the feeling, so it stayed in.) When he recorded "I Don't Mind" on September 27, 1960, guitarist Les Buie screwed up, coming in slightly too early for his solo; Brown liked the mistake so much he insisted on keeping it. Actually, the entire song has a slight air of off-ness to it. The bunched-up triplet rhythm that leads into every verse tends to speed up, the chord sequence is bizarre, and the Famous Flames are having a rough time trying to keep their place—you can hear them adjusting their notes, moment by moment. (It can't help that they start singing an "oh-oh-oh" for a few bars before the lead singer deigns to join them.) "I don't mind," Brown insists; "Idamind!" his Flames chirp back, mockingly. And the "you gonna miss me" that ends every verse is followed by a pregnant gap where the next downbeat is supposed to be. It was appealingly weird enough that it became a hit (No. 4 R&B, No. 47 pop).

The Live at the Apollo version follows the general blueprint of the studio recording, but accentuates its weirdness. Fats Gonder plays organ rather than piano, which plays up the chords' awkward swerve through sevenths and thirteenths, the kind of intervals that would form the backbone of Brown's funk period, starting a few years later. The Flames are a bit more locked into their peculiar backup moans, and switch between wordless vowels ("ohhh," "iiiiiiiiii," "eeee") and the response to Brown's "I don't mind" is compressed into something so brief it sounds like an "aua"; Buie reprises his guitar mistake in a studied way. As soon as Brown comes in, there's an all-but-inaudible dispute in the audience—a woman yelps something, a man answers her crossly. The guitar break's sole lyric (an antecedent-less "somewhere down the line") has its mystery deepened by a vocal-mic dropout that would be unacceptable on a studio recording and appears to turn it into "somewhere I'm down tonight."

The last "you gonna miss me" is answered by a woman in the crowd, yelling encouragement: "I sure do, baby!" This isn't the last time we'll hear her voice on the record. In The Godfather of Soul, Brown spins a story about how, when they were test-recording the earliest shows that day, "a little old lady down front kept yelling, 'Sing it mother_____r, sing it!"' (sic), and how the Live at the Apollo project's coordinator Hal Neely bribed her to stay for the day's remaining shows, but moved the microphone so it couldn't pick her up quite so well. It's a good story, anyway, and Neely tells the same yarn.

But maybe Brown is trying to drown her out, or getting frustrated at how someone might be ruining his expensive live recording: for the "goodbye, so long" right after that, he's almost shrieking. He brings his voice back down quickly—"no no no no"—then swerves away from the mic to sing a last few words and cue the band to end the song.

Shares