Joe Lieberman is chiefly remembered as Al Gore's vice presidential running mate in the 2000 presidential election, and for good reason: He not only was a trailblazer as the first Jew to appear on the national ticket of a major party, but he also ran in a historic election that was so hotly contested it ultimately had to be decided in a 5-4 vote by the U.S. Supreme Court.

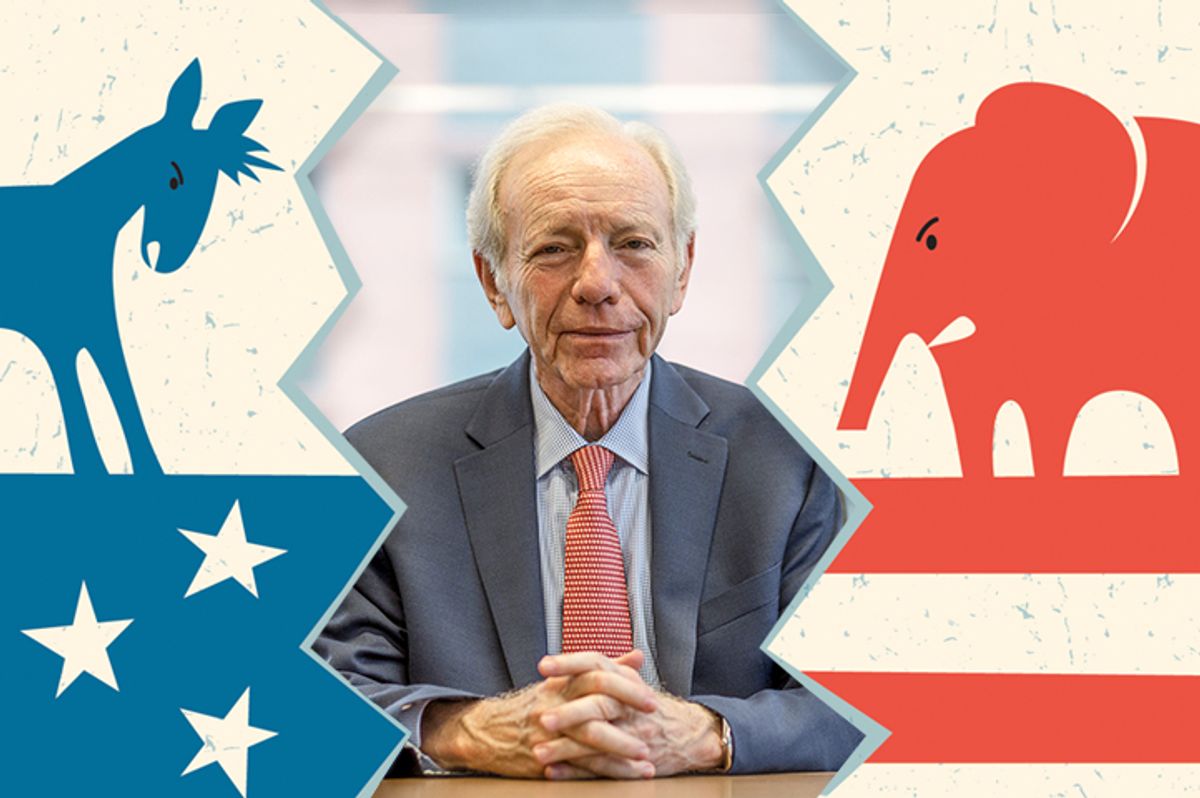

Yet Lieberman's career should be remembered for more than this single incident. During his 24 years representing Connecticut in the U.S. Senate, from 1989 to 2013, he became a prominent advocate of bipartisan compromise, or centrism. In his final Senate race in 2006, Lieberman actually lost the Democratic primary in Connecticut, but was re-elected anyway as a third-party candidate. He endorsed John McCain over Barack Obama in 2008 -- and spoke at the Republican convention that year -- but supported Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump in 2016. During his conversation with Salon he elaborated on why he feels the values of middle-way bipartisanship he has long represented are still important in an era of bitter and entrenched political division.

Your Senate career, spans almost a quarter-century, and I'm sure you saw a decline in bipartisanship during that period. Let's start from the beginning: When you first joined the Senate, what experiences did you have that demonstrated the character of bipartisanship in Washington at that time?

I mean, this is really important to me, because among the various things that ail the American government today and breed dysfunction, probably the No. 1 cause is a lack of centrism. And by definition, I think I should start by saying that centrism is not just sort of coming to a mushy middle, a moderate on everything. Centrism is really a kind of strategy — not even so much a philosophy, it's a strategy to make government work.

It's based on the premise that to get anything done, people have to compromise and come to the center, come to common ground ... In other words, you can be left, you can be right on a given issue — another part of centrism is being independent, I think — so you don't feel that if you're a member of a particular party, unless you believe every one of the tenets of its platform, you have to follow that all the way. That was never the way in American politics. It seems to be what the parties are holding their members to now, and that discourages the kind of compromise that gets you to the center to get something done.

So it's really as much a strategy as a philosophy. ... Sometimes when you say "centrism," people think, "Oh, that's just status quo. You're just trying to stop change." In fact it's the opposite, because you've got to compromise to get things done, to change the status quo.

You played a prominent role in getting the public option removed from the Affordable Care Act in 2010. You also played a role in hammering out certain other details regarding the bill. How do you feel about that history now? What message does that send to politicians working on these issues in Washington right now?

Just to view the Obamacare legislation in brief historic context: The first major piece of legislation that President Obama considered in 2009 was the so-called stimulus act ... Because I was known as a centrist, a moderate, an independent, both the Obama White House and [then-Senate Majority Leader] Harry Reid basically asked me if I would help in outreaching to some of the moderates. You know, you needed 60 votes at that point for everything. So I did — particularly Susan Collins, ultimately Olympia Snowe and Arlen Specter. And not every Democrat voted for it, so that got the 60 votes. It took a lot of political capital to get that done and the Republicans who voted with us were really chastised within their party.

So when we got to Obamacare, which was the next priority for the Obama administration, though we worked on it, worked on it a lot with some of those same people and others — Arlen Specter, Susan Collins, Olympia Snowe — It became clear as it went on that there were gonna be no Republicans. And at that point, they had 60 Democrats ... We needed every Democrat, so in a way I was the 60th, although there were probably three or four others who would say that they were the 60th vote.

And therefore the negotiations all occurred within the Democratic Party. So it was still necessary to come to the center, but the center now was to the left of center.

And so within that context, the question of the public option was one of your sticking points. What made you choose that issue?

Well I had priorities which were quite similar to what most of my fellow Democrats had. I wanted to have a health care system that covered more people. There were too many people in America who didn't have health insurance. I wanted to have a health care insurance system that didn't charge a much higher price or refuse to cover people who had a pre-existing illness. Those were the people who needed health insurance the most. ...

When it came to the so-called public option, particularly because I thought the Obamacare exchanges would cover some of the people that I was worried about — not only poor people, but poor people are covered by Medicare and Medicaid, and Medicaid was going to be expanded under this, which I thought was fine — there was a sort of group ... who might be forced to retire before they were eligible for Medicare. And the Obamacare legislation gave them the right to go on the exchanges and buy insurance, presumably at a lower price.

Here is where two ideas that I had conflicted: One was an ongoing concern ... from the early '90s about the rising national debt. And of course it's still rising. I was very concerned about the cost of the Obamacare legislation overall, although the Congressional Budget Office in the end said it would not add to the deficit or the long-term debt. But I thought, oh my goodness, the public option is really, it was pretty clear, the way to put a foot in the door for a total national health insurance program. ... First I thought it could really bankrupt the government, and secondly I could go back and look at it at some future time to see whether we could really afford it. So that ended up being something that I held out on.

Shares