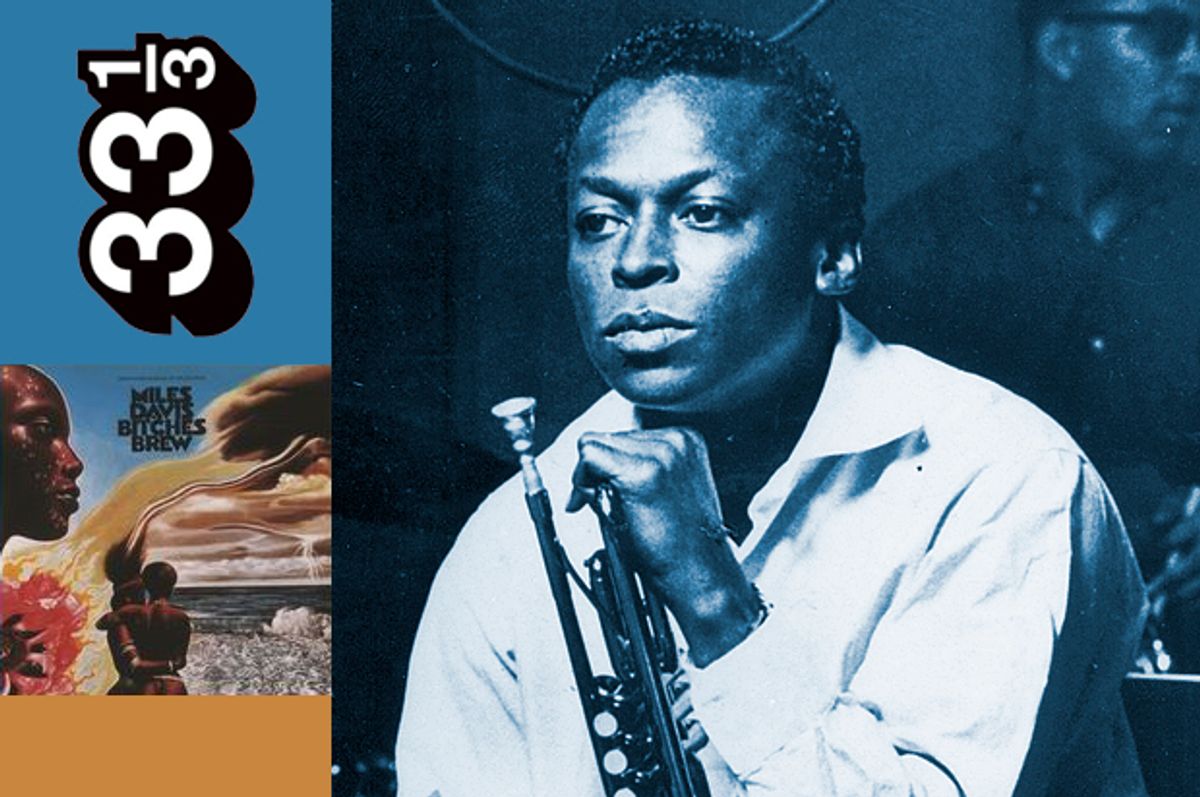

In an era awash in commodified violence and gore — death metal and dark industrial, serial killer studies, Headline News Network, embedded war reporters — the opening seconds of Miles Davis’s album, "Bitches Brew," remain the single most ominous thing in the infinite man-years of experience and consumption that pop culture has produced.

LP 1, Side A, Track 1: “Pharaoh’s Dance.” The first sound is Jack DeJohnette, one of two drummers, coming out of the right channel, keeping a quiet, insistent beat with quarter-notes on the snare and eighth-notes on the hi-hat. A quick bass drum rhythm — still quiet — near the end of two bars announces Chick Corea’s entrance on the electric piano. Also in the right channel, Chick is one of three keyboard players on the track (still waiting to enter are Larry Young in the middle and Joe Zawinul in the left channel). He’s playing a short, repeated fragment that might turn into a longer melody if the music were given enough time to develop.

But that doesn’t happen. Bennie Maupin’s bass clarinet and the electric guitar of John McLaughlin quickly join in with their own insistent repetitions. Lenny White taps his hi-hat in the left channel. Zawinul picks up the theme, such as it is. Young fills in a chord.

There’s no climax, no building to something greater and more developed. Almost immediately, the music comes to a halt, collapsing. Dave Holland answers with a rising arpeggiated octave on the acoustic bass. If this were all louder, the music might be representing an argument. The watchword, though, is quiet — the voices are all at a murmur, yet they carry a weight of intensity, as if the thing they are trying to articulate is just past the edge of language. There’s no identifiable hint of a song, the music sounds ritualistic. The way it whispers, the way it seems to follow the rules of a trance, the way it does not reach, or even seek, finality, make it existential.

I was probably fifteen when I first heard the record, down in the basement at my friend R’s house, after high school. It might have been his record, or it might have been his parents’ (they had a decent jazz collection). We played together in the school band (he played trumpet and I flute, and later baritone and tenor saxophones), and we were getting into jazz. For us, that path started with the contemporary leaders of fusion: Corea and his Return to Forever band, Stanley Clarke and his tremendous "School Days" album (one early, memorable concert we saw was Clarke, with Tower of Power as the opening act, but our very first concert was Jack Bruce and Friends in 1980), "Chameleon" and "Thrust" from Herbie Hancock.

Working backwards, we had found our way to a little bebop, but mainly to the first great Miles Davis Quintet, with John Coltrane on tenor, Red Garland at the piano and the incomparable rhythm section of Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, bass and drums. We were astonished that "Birth of the Cool" came from the same man. Miles’s restlessness confused us. We listened to a lot of great musicians who lit a fire when they were young, then stoked those same embers successfully for decades. We heard Sonny Rollins take apart his own playing and put it back together again in a new way, but no one else did what Miles did, shed one style after another — and not just styles but revolutions! He had a seeming discontent with success, and when other musicians began to follow his lead, he had to do something different.

Somehow, we stepped sideways and forward, and found ourselves listening to "Bitches Brew," and that knocked us into another dimension.

It’s no exaggeration to say those opening bars disoriented us. We had trouble comprehending them. R would pick up the needle after those several seconds, put it back at the beginning, and we would try to listen again. After a few more times, we would stop and sit and talk and think. What disturbed us was not just the ominous tone the music carries with it like a bulldozing, inexorable force, but that we didn’t understand what was happening, how the music was made, how people could play that way, how they could think that way. Excavating my memory and imagination retrospectively, the sensation was like what the first encounter with a living alien civilization might be like, recognizably sentient beings communicating in a language that can express the most advanced concepts via what appear to be atavistic materials. "Bitches Brew" challenged the neat certainties of our youthful outlook.

We were playing jazz halfway decently already, and we understood tunes and chord changes and fitting a solo into that context. We knew how to organize our shit. But "Bitches Brew," we could not understand how it was organized; we could not understand how each note determined the next one. It wasn’t haphazard, it made sense, and the fact that two bassists, two drummers and three keyboardists could play simultaneously, making the same music and keeping every note clear, was proof. It was the sound of a brilliant, profoundly restless musician, tired of his past and dissatisfied with the direction of the music he heard around him, using more than a little violence to force open a new path.

We were fifteen, so what did we do? We turned our sunglasses upside down and talked about the record among our friends while we made sure that we did so in crowds, so that our peers could overhear how cool we were. And we listened, because the dark beauty of the music and the unlimited possibilities it promised were irresistible.

Shares