It is somewhat fitting that “The Gilded Age,” the latest installment of the PBS series “American Experience,” kicks off with the story of a hotel orgy. Of wealth.

The setting is an extravagant gala that took place at Waldorf Hotel, which attracted everybody who was anybody in New York City. Photographs of attendees are styled to resemble portraiture of European aristocracy, with elaborately dressed and coiffed men and women engaging in what appears to be an insane game of one-upmanship. Other photo portraits of an earlier ball hosted by the Vanderbilts in 1883 are more ridiculous yet. In one, a woman wears a luxuriously feathered hat. Another features a lady of means sporting an entire taxidermized bird on her head. Both may have been outdone by one person who has made a jaunty chapeau of what appears to be half of a feline. Yes. A cat.

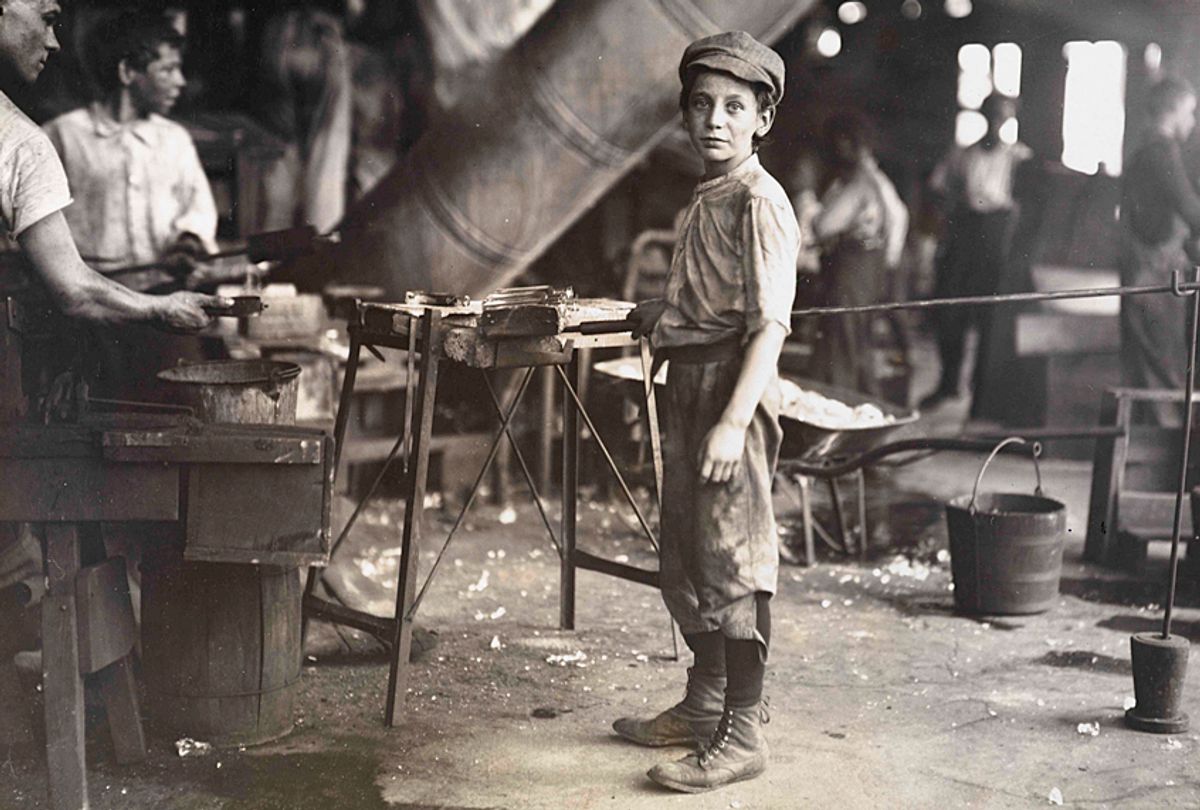

Though this event is meant to announce the Vanderbilts’ place in the upper crust of society, all of these visuals stand as history’s testament to how insanely broad the chasm between rich and poor had become. To contrast this opulence the documentary’s director and producer Sarah Colt includes many photos of the less fortunate and includes a brief account of an impoverished mother who records she has spent the last cent she has and was forced to send her children off to work without food.

“The Gilded Age,” premiering Tuesday at 9 p.m. on PBS member stations, isn’t the first work to observe the distinct parallels between today’s political and economic landscape and the era comprised by the three decades following the Civil War’s end. Nor will it be the last.

At the moment, in fact, the era appears to have something of a romantic aura about it. Its very name is fascinating, with its implication of excess and glorified ostentatiousness. NBC is betting on the universality of period’s allure, in fact, to ensure the successful launch of its own scripted take: “The Gilded Age,” from “Downton Abbey” creator Julian Fellowes, is set join the broadcast schedule in 2019.

Before this FX will debut its drama that follows the Getty family, a clan whose wealthy was built after the Gilded Age faded but whose foundational members both emulated and learned from the mistakes of its predecessors.

Like all the names remembered by history the Astors, the Vanderbilts, industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and financial giants such as J.P. Morgan carved out reputations that remain with us today. They are held of as examples that ours is a system in which anyone with pluck, drive and nerve and claim the millions waiting as a reward for their ingenuity and hard work.

This is the part of history’s refrain that’s glamorous and easy to remember. The part about “The Gilded Age” so many forget, as historian Nell Irvin Painter describes, is that the era’s title represents a wide deceit committed upon Americans. At that time of that Vanderbilt gala, the majority of America’s economic fortune was tied to around 4,000 families, less than one percent of the population. Together this small group held as much wealth as the other 11.6 million families combined.

The richest represent a patina, a shiny exterior camouflaging the rot underneath.

Never does the “The Gilded Age” point out the similarities and connections between the parallels between the turn of the 20th century and the times we’re living in, but it doesn’t have to. Those photos and the description of the lengths to which Alva Vanderbilt goes to ensure her family’s brand is promoted in the press can be thought of as the ancestor of social media.

The Vanderbilts still have prominence in our culture, thanks to Gloria and her son and Anderson Cooper. But the family in their heyday bears more than a few similarities, perhaps, to the Kardashian-Wests.

Even the how of their wealth building may seem familiar to anyone with a passing knowledge of the history of today’s tech giants, as the country’s capitalist system transformed from a structure based upon localized commerce with one dependent on an urbanized workforce tied to industry and connected by new means of shipping. At the turn of last century, it was railroads. Now, it’s planes.

All of these alterations changed consumer habit and, in turn, shifted the distribution of wealth and the power ordinary citizens have to impact our democracy.

Still with us as well are the old ideas that America’s poor somehow deserve their lot, which leads into a political history that receives a profound examination of “The Gilded Age.” This counterbalance to the tales of Morgan’s aggressive bombast tells the stories of Mary Elizabeth Lease and Henry George, whose efforts spurred a swell of working class populism that threatened to topple the two-party system.

They did not succeed, as we know, but they posed the same issues with which we’re wrestling now, as we look toward a midterm election season seeking to course-correct from a path that has led American to its current socially and politically riven state.

"The essence of democracy is equality. Everybody gets one vote,” historian H.W. Brands observes in the “The Gilded Age," “The essence of capitalism is inequality.”

The question, then, is as classic as that black and white archival footage: Who does government truly work for?

As a history lesson “The Gilded Age” is constructed to be as pleasing to view as its information download can be stunning. Photos and sketches of the legendary Vanderbilt mansion and other architectural markers of wealth are impressive by today’s standards. Beyond all this, there is a comfort in the work’s caution, in that this time period stands as proof that we’ve been to this brink, tumbled over its cliff, survived and returned. Perhaps we’ll learn from the mistakes of yesteryear’s titans. But that requires scratching beneath the veneer of gold that seeks to distract us, even now.

Shares