We squirm when we read our middle school diary entries. We laugh nervously at an overconfident contestant belly flopping on a talent competition. And one person's romantic wedding proposal in the park is a passerby's cause for wincing.

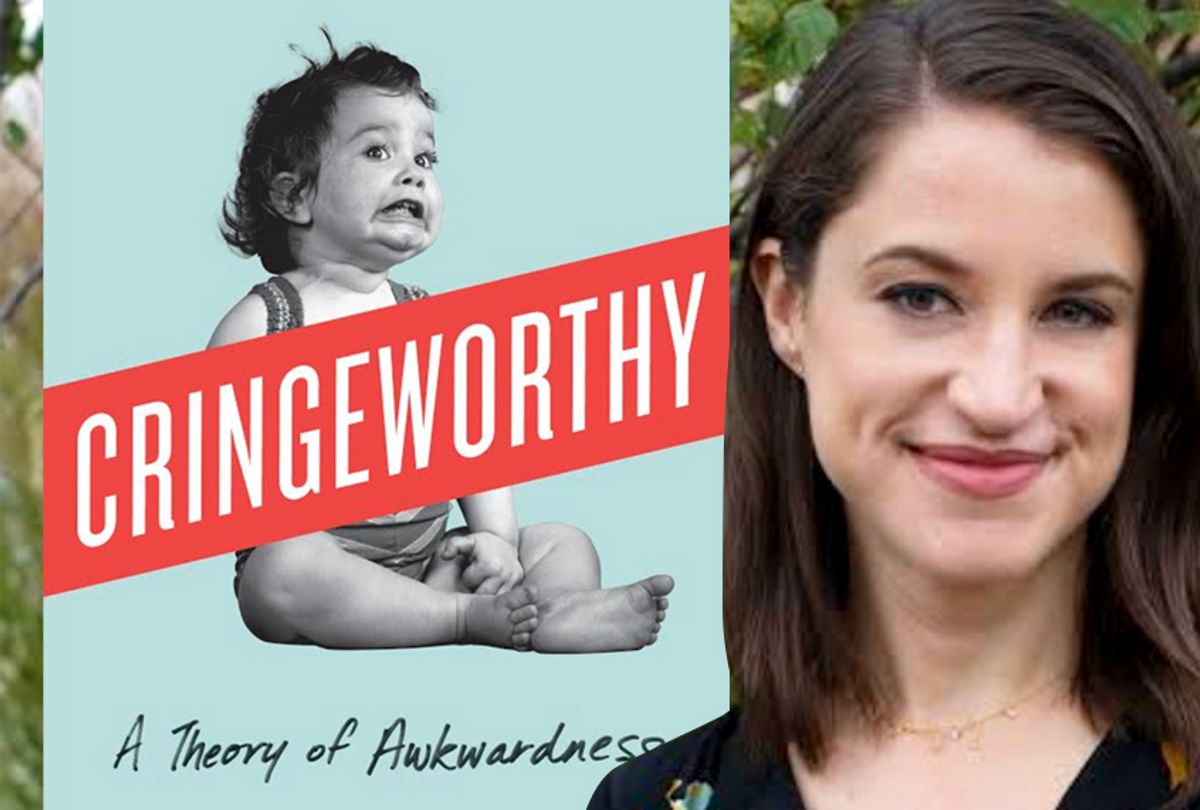

Melissa Dahl, a senior editor for New York Magazine's The Cut and co-founding columnist for its Science of Us, wanted to know why. The result of her inquiry is "Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness," a lively, funny and often deeply personal investigation into the things that make us shudder. Salon spoke recently via phone to the author, on the benefits of blushing.

Of all the things you write about, why this for a book?

It’s a feeling that’s driven me nuts my entire life. And also, it cracked me up. One thing that I was really happy about having this as a subject was, every time I write about it, just made me laugh. I just thought so much of this is so funny.

You talk about these ideas like "All the world is a stage" and what that truly means. Cringe-worthiness often comes from not being able to reconcile the identity that we think of ourselves as and an identity that we are playing, whether it is our past self, or whether it’s literally the reflection in the mirror.

I wrote a piece for Science of Us about why you cringe at the sound of your own voice. And it’s becoming a cliché, but we can all say that everybody kind of says that. It became really interesting to me to figure out what that means.

There’s a psychological explanation to the voice thing. Hearing my voice talk right now, I’m hearing it through the air, and I’m also hearing it through the bones in my own skull, which transmits the sound at lower frequency than other people are hearing it. So that’s one reason why, when you hear your voice played back, it’s really common for people to feel like, “Gosh, I sound like a chipmunk; I sound like a teenager; why does my voice sound so high?” It really is true that the way you’re perceiving yourself and the way someone else is perceiving you are different. But I think of that a little bit further. Okay, but why does that make us cringe? We all have these idealized versions of ourselves we carry around in our own heads, and then there’s that self that is actually running around out there in the world that other people are seeing. We’d like to think those two things are one and the same, and sometimes, they are. But I think a cringe-worthy moment is when those two selves collide, and you realize, “Oh, my gosh, I’m not coming off the way I thought I should be. I did not intend it this way."

We may cringe at the sound of our voice or we may cringe seeing ourselves in a photograph, but that's not necessarily cringe-worthy to anybody else.

That’s so great to keep in mind. Sometimes you can coach yourself through these embarrassing moments and just say, “OK, not everybody is taking this as seriously as I am or as I think it is.” But I also have come to think that sometimes that gap can be useful. I think cringe-worthy moments force you to think outside of your perspective and make you look at yourself through someone else’s point of view. These little moments became so fascinating to me.

You talk about when you feel embarrassed for someone else — the Michael Scott thing where the other person isn’t cringing, but you’re cringing because they’re not cringing.

It made me think about empathy in maybe a different way than a lot of us use it. There’s this study I’ve actually written on a couple of times, where people who are more likely to cringe at other people’s embarrassing moments are often likely to be empathetic.

The first time I heard that, I felt unbearably smug because I just leave the room when people are embarrassing themselves. I can’t stand it. But it made me think of it in a different way. Empathy is putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, but it’s still you in there. Like maybe I’m feeling embarrassed for somebody else because their fly is down or something, but is that empathy if they don’t know they’re embarrassing themselves? I think it goes back to my cringe theory, when we sense this gap in someone else when they think they're presenting themselves to the world in one way but they actually coming off a different way and they can't see that.

There’s this psychologist Philippe Rochat, who argues that empathy is an automatic response. It’s something that typical brains do automatically. You can process that feeling in one of two ways. You can feel contempt for the person and push them away, or you can respond in compassion and recognize yourself in embarrassment — which is harder to do and sometimes less attractive than to just sit back and laugh. The compassionate response is, "I’m also an idiot; that’s why I feel this way for you."

There’s another side of this, where you became embarrassed retroactively. You cringe reading an old diary, or write something you feel OK about, and then someone calls you out and then suddenly you are horrified. You can have cringe-worthy-ness imposed upon you.

I’ve been writing for ten years. I’ve got ten years worth of embarrassing stuff behind me. It helps to think of past Melissa as a separate person. Like, "Oh, look at her, she was just trying her best. Good for her." That’s how I started to think that helped me reframe that horrible cringey feeling of, "Oh, what was I thinking?"

With social media, the risk of mortification feels like now it might never go away. There might be no expiration date.

There might not be, and it’s an argument for getting more comfortable with your past self. As kids grow up posting everything online, I wonder what’s going to happen. I think it’s worth probably all of us getting comfortable with people we used to be.

You talk about the value of awkwardness and how being able to feel awkward, being awkward for ourselves, for someone else, can be very positive.

When I first started looking at this, I thought, OK, awkwardness is beneficial because it alerts us to social norms that are inherent but maybe not spoken out loud. I think that’s true. But for me, after obsessing over this feeling for a couple of years, it became valuable in a different way that I was not really expecting. I started getting this awesome common humanity vibe. If you’re feeling awkward or uncomfortable, it's because you are imagining what someone else is thinking of you. An example is when someone is walking down the hallway and you’re walking towards someone and then you both move one way and then one moves the other way and someone says, "Shall we dance?" Now it just makes me laugh. These little moments are cracks in our cool personas. They highlight the innate absurdity of being human and make me feel more connected to people when the feeling comes around. To me, it became a reminder to just lighten up. These moments aren't so bad, and it can actually be funny and weirdly connecting.

I wonder about this culture now, that’s both about shaming and awkwardness and such profound narcissism, where kids are trying out there in social media to be an absolute, most perfect self.

I hope there is some value still in putting away your private self in a journal or somewhere. I don’t know. I wonder if teens still have journals. I hope they get a record of who they really were without filter.

I think what’s interesting about creating an idealized version of yourself is that you’re creating an idealized version of yourself from a 13-year-old’s perspective. I think, looking back in a couple of years or a couple of months or even a couple of days, they might find that cringe-worthy. It’s still a feeling that’s going to come back. All I can think is, this past you is going to stick around more than she used to. It's worth making friends with her, whoever she is, no matter how much she embarrasses you.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Shares