In 1974, as the White House, Congress and the Supreme Court were playing out the endgame of Watergate, a letter appeared in Time magazine that I still remember 26 years later. "I am tired of the defense 'But he is the president,'" wrote the disgusted correspondent.

Those who lived through Watergate remember that defense in all its permutations. We heard it, of course, from Nixon loyalists, and from people who thought that perhaps he had done something wrong but that he still deserved the respect of his office. And we also heard a variation of "But he is the president" from the veteran journalists who were certain that the Washington Post was making a fool of itself by placing any trust in the suspicions of two young police beat reporters named Woodward and Bernstein.

"But he is the president" survived Nixon's presidency, and it took on various new permutations over the years: "But he is a master of foreign policy," "But he is a commanding intellect," and, finally, "But he is dead." A great sick joke if it weren't such an appalling spectacle, Nixon's funeral was an extraordinary feat of posthumous ass-kissing. Not just by the cronies you'd expect -- Bob Dole, Henry Kissinger, Billy Graham -- but by Bill Clinton, flanked by his wife, who had worked on the staff of the House Judiciary Committee during Nixon's impeachment hearings. The only journalist who avoided the sickening piety that carried the day was Hunter S. Thompson. Writing in Rolling Stone, Thompson spared no one's feelings; he wrote to draw blood. His obituary for Nixon descended directly from a line of American journalism that included H.L. Mencken's obit for William Jennings Bryan, a piece whose words could have easily applied to Nixon: "a vulgar and common man, a cad undiluted. He was ignorant, bigoted, self-seeking, blatant and dishonest. His career brought him into contact with the first men of his time; he preferred the company of rustic ignoramuses." Those who deigned to acknowledge Thompson's piece tut-tutted about its inappropriate tone. "After all," more than one person said to me, "the man is dead."

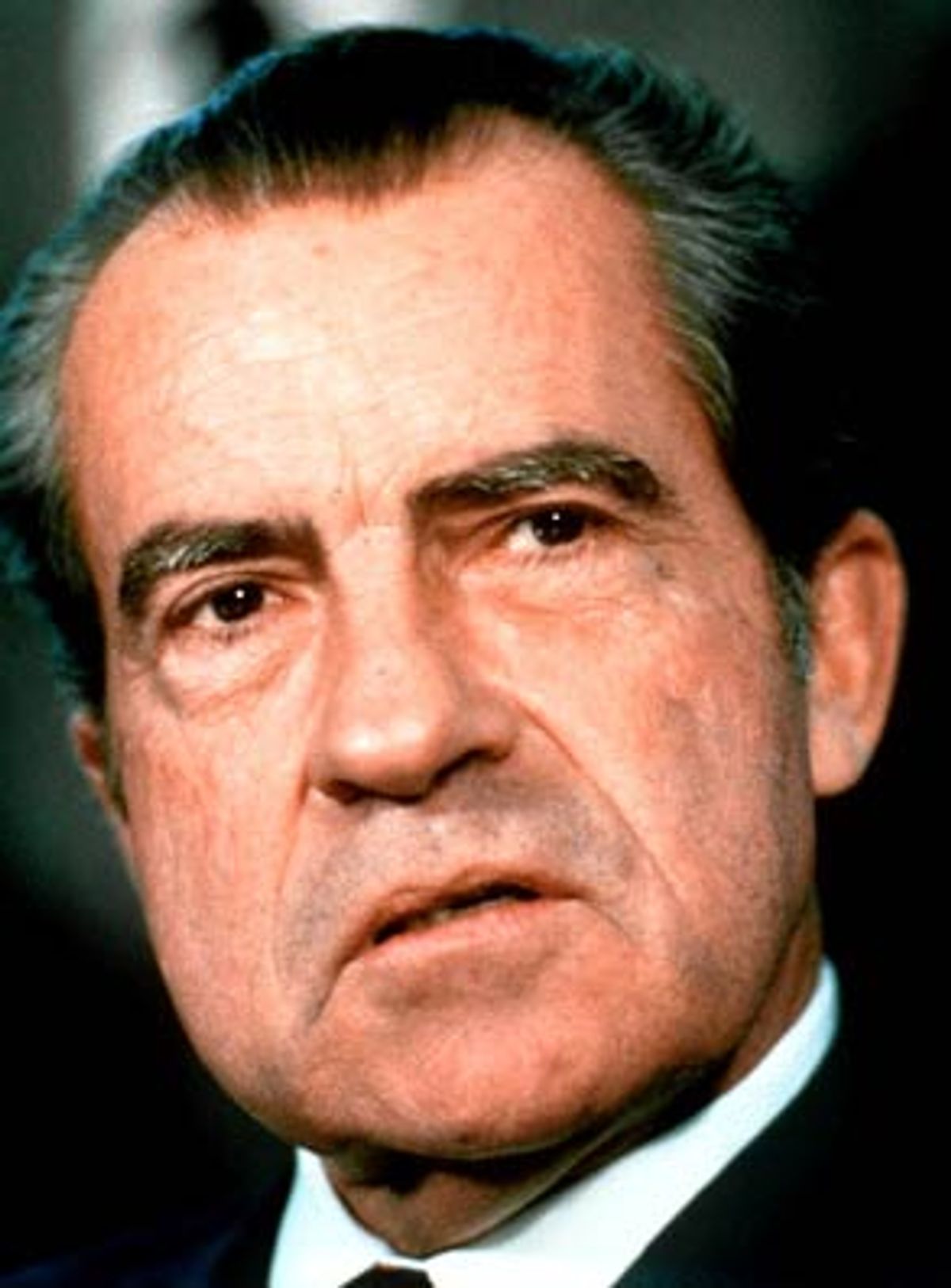

But is he? Will Richard Nixon ever be dead? He rose from losing the presidential election in 1960 and the California gubernatorial election in 1962. He even recovered from being the only president to resign from office, rising to the level of elder statesman, thus joining whores and ugly buildings as one of the three things that gets respectable with age. On "Saturday Night Live" Dan Aykroyd played Nixon as an impossibly oily ghoul, rising again and again, vulnerable only to a wooden stake driven through his memoirs.

We should be thankful then to the British journalist Anthony Summers, who, in his new "The Arrogance of Power: The Secret World of Richard Nixon," tramps the grave dirt down. Simply by telling us, in his prologue, who attended Nixon's funeral and who didn't, Summers ties Nixon to: huge payoffs from Howard Hughes, the laundering of the profits of a Bahamian casino, illegal campaign contributions from the likes of Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi and the military junta that took over Greece in 1967, access to U.S. arms given to the Shah of Iran without the consultation of the American government, the illegal derailing of the Paris peace talks, and, of course, the host of crimes contained under the umbrella of Watergate.

Summers offers a wealth of skulduggery and deceit that, you might imagine, would keep journalists busy for weeks. But instead the advance reports on Summers' book illustrate the debased nature of what currently passes for political journalism. They have almost all focused on just one of his allegations: that Nixon beat his wife, Pat. "The most provocative charge in the book," reported the New York Times last Sunday. More provocative than Nixon's almost-certain interference with the Paris peace talks? Than his probable involvement in schemes to assassinate Castro that predated the Bay of Pigs? More provocative than the charge, confirmed by Nixon's Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, that the president was so unstable during the final days of his administration that Schlesinger instructed the Joint Chiefs of Staff not to react to any military orders from the White House unless they were first cleared with him? Even Vanity Fair, in the excerpt it ran from Summers' book, went with the section on the Paris peace talks. What kind of alternate universe are we living in, where Vanity Fair understands what the important news is better than the New York Times?

As it turns out, the wife-beating charges are the least substantiated in the book. The abuse may very well have happened, but Summers can't do better than "The doctor who treated [Mrs. Nixon], [Seymour] Hersh told the author, corroborated the story." An endnote informs us that Woodward and Bernstein also heard the story but were unable to corroborate it for inclusion in "The Final Days." Perhaps Summers simply couldn't resist relaying it, but it's certainly not his fault that the reports on "The Arrogance of Power" have barely scratched the surface of the intrigues that Summers corroborates so damningly.

The challenge facing the biographer who takes on Richard Nixon, Summers writes, is having to chart "a careful passage through a minefield of lies." There's another challenge: the unacknowledged seductiveness of Richard Nixon. That notion may sound funny to those of us who hear the name Nixon and see the familiar caricature of sweaty jowls, stooped gait, beady eyes and ski-slope nose. But Nixon, perhaps more than any other reviled figure, was always remarkably adroit at getting his observers to see him in his terms.

Nixon's hatred for the privileged Ivy League tenor of the Eastern establishment was real despite, Summers demonstrates, the fact that Nixon's own upbringing was nowhere near as deprived as he liked to paint it. But some writers have seen Nixon's feelings of class resentment sympathetically, rather than as the root of a pathology. Perhaps they have been swayed by the opening cadences of Nixon's autobiography ("I was born in the house my father built"), promising a story of greatness rising from humble origins and deliberately invoking the myth of Lincoln raised in a log cabin. Or they may be moved by the lack of affection in Nixon's family. "Can you imagine," Kissinger is quoted as saying, "what this man could have been had somebody loved him?"

In the years following Watergate, as dirty tricks that Nixon's political opponents used against him have come to light, some observers have stooped to the rationale used to justify Nixon's own dirty tricks during Watergate: Everybody does it. Tom Wicker called his Nixon book "One of Us" and claimed that the reason Nixon repels us is that we see our own failings in him. But how many among us can say that our everyday failings include needlessly prolonging and illegally expanding a war and provoking a constitutional crisis?

The most laughable of Nixon's apologists is Oliver Stone. In his film "Nixon," he re-created Nixon's famous predawn trek to the Washington Monument to speak with antiwar protestors, but with one significant addition. Confronted by a girl who asks him why he doesn't simply end the war, Nixon hesitates and the horrorstruck girl realizes the truth. "My God," she says, "you can't stop it, can you? It's out of your control." Hustled away by Secret Service agents, Anthony Hopkins' Nixon says that this girl knows what it took him years to learn about politics. Of all the times that the movies have rewritten history, there is no more ludicrous claim than that the commander in chief is powerless to end American involvement in a war.

Witnessing such justifications coming from people who are not stupid is something akin to seeing a man raised on Shakespeare weep over "The Waltons." They are the intellectual equivalent of Nixon's peerless manipulations, the Checkers speech or the use of his dead mother ("My mother was a saint") in the moments before he left the White House in disgrace. Falling prey to Nixon's transparent sentimentality they shrink queasily at the prospect of confronting him for what he is, as if to do so would make them the schoolyard bully picking on the kid who never fit in.

Over and over since his death, Nixon's biographers have told us that he was a very complex man. Bunk. Lying and deviousness are not the same thing as complexity. Nixon was not Macbeth, or even Iago. He was too puny. As Norman Mailer so brilliantly put it, remarking on the 1960 presidential nomination, Nixon's ascension was "the apocalyptic hour of Uriah Heep."

Summers doesn't fall for the complexity argument. The strongest aspect of "The Arrogance of Power" is the case it makes for Nixon as the most consistent of men. Seen in the context of the lying, cheating and lawbreaking that characterized every aspect of his political career, Watergate was not Nixon's self-destruction but his fulfillment, the essence of everything he stood for. Nixon's apparent mental breakdown toward the end of his presidency, likely exacerbated by his abuse of the anti-epileptic drug Dilantin as a tranquilizer and his drinking problem (which accounts for his frequent slurred speech and disassociated demeanor), reads here as a moment of self-definition.

Nixon had been stripped down to his motivating essence, his self-serving lust for power. So much so, Summers writes, that in a visit to the Joint Chiefs of Staff as Watergate revelations traced the misdeeds ever closer to him, Nixon said, "We gentleman here are the last hope, the last chance to resist." Chief of naval operations Adm. Elmo Zumwalt said, "One could come to the conclusion that here was the commander in chief trying to see what the reaction of the chiefs might be if he did something unconstitutional ... He was trying to find out whether in a crunch there was enough support to keep him in power."

As frightening as it is to think of Nixon's floating the idea of a military coup, the notion is the logical extreme of the scheming he had already orchestrated following the break-in and throughout the Senate hearings. In her "The Mask of State: Watergate Portraits," Mary McCarthy writes of Nixon as so accomplished a manipulator that he was able even to find the weak spot of Sen. Sam Ervin, playing off his fear of increasing pressure on the president during the looming international crisis of the 1973 Middle East War. Perhaps Ervin wouldn't have worried so much had he known what Summers reveals here. On Oct. 23, 1973, Kissinger was told by Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin that the Soviets could very well be sending troops to the conflict. Kissinger, attempting to get in touch with Nixon, was told by chief of staff Alexander Haig that Nixon had "retired for the night." While the United States went to DEFCON III, preparation to launch a nuclear attack, the president of the United States was passed out, drunk. (Haig still denies this. Kissinger's aide, Roger Morris, has quoted Kissinger's assistant Lawrence Eagleburger saying that it did happen.) Kissinger handled the crisis and the Soviets backed down.

That's the most frightening of Summers' revelations. It is not the most nefarious. Some of the episodes described here have already been well-documented, like the 1950 California Senate campaign against Helen Gahagan Douglas that earned Nixon the nickname Tricky Dick. In the campaign, Douglas was smeared as a Communist (the "Pink Lady" she was called) and anonymous calls were placed to voters asking if they knew she was Jewish (she was married to the actor Melvyn Douglas). But others, some of which have been hinted at for years, are detailed more convincingly by Summers than they have ever been before.

Taking the advice that Deep Throat gave to Bob Woodward, "Follow the money," Summers is able to chart much of Nixon's dirty dealings by laying out who bankrolled him. He makes a very convincing case that Nixon received millions of dollars from organized crime, much of channeled through his friend Bebe Rebozo. Money may also explain why Nixon chose Spiro Agnew as his running mate. (The announcement had caused gasps from the floor of the 1968 Republican Convention and prompted a famous Hubert Humphrey ad in which hysterical laughter is heard over the image of a TV screen bearing the legend "Agnew for Vice President.") Thomas Pappas, an immigrant Greek millionaire who passed on $549,000 in contributions for Nixon's 1968 campaign from the military junta that overthrew the Greek government, had "put in a good word for Spiro" with Nixon, who later admitted Pappas influenced the selection.

Summers is equally convincing when arguing that the reverberations of Nixon's preoccupation with Fidel Castro may have extended to the Watergate break-in itself. It's likely that Nixon (whom Haig describes as "Eisenhower's point man [on Cuba]") was in on Operation Pluto, the Eisenhower-approved CIA plan to get rid of Castro. Nixon had good reason to fear that, if these plots became public, he along with JFK would be disgraced. There are several instances on the Watergate tapes where he frets about what the FBI investigation of Watergate will uncover about CIA plots to kill Castro. Howard Hunt, one of the Watergate burglars, was involved in those plots as well. At the time of the Watergate break-in, Democratic National Committee chairman Larry O'Brien was working as a consultant for Howard Hughes, and Nixon may well have feared that O'Brien had information on Nixon's knowledge of CIA plots against Castro, or at least of the hundreds of thousands of dollars Hughes had been funneling to Nixon going back to the '50s.

For sheer rottenness, though, none of Summers' revelations can touch his new information that Nixon was probably involved in a scheme to derail the Paris peace talks in 1968. In my opinion, no revelation about anyone who has ever held public office in this country equals it. Nixon's plot to keep South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu away from the talks has been rumored for years. LBJ had FBI information on it which he passed on to Humphrey in the days leading up to the 1968 election. Fearing that it wasn't solid enough, and that it would look like a last minute attempt to sway the election, Humphrey backed off.

That must be counted among the most tragic miscalculations in American politics because only a fool would doubt Nixon's involvement. Some writers, most recently Robert Dallek in the second volume of his LBJ biography, have made strong cases for it. Summers' is the strongest, not just because of recently declassified FBI files but because of his interviews with Anna Chennault, a well-known lobbyist for the Nationalist Chinese. Nixon and John Mitchell instructed Chennault to tell Thieu he should hold off on joining the talks to help Nixon get elected to the presidency, after which he would get a much better deal. Nixon's public stance during all this was one of committed patriot, refusing to make political capital by commenting on Vietnam during LBJ's announced bombing halt which, Johnson hoped, could lead to a break in the war.

Of course, there were plenty of reasons for Thieu to back out of the peace talks even without Nixon's encouragement -- most of all, the fear of his government's collapse. And even had he agreed to the talks, there was no guarantee that the talks would have led to an end to the war or even to a Humphrey victory. All that is irrelevant. What is relevant is that Nixon, as a private citizen, conspired to affect the course of American foreign policy by sabotaging peace talks that could have prevented the deaths of thousands of American soldiers (not to mention hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, civilians as well as combatants). In other words, Nixon committed treason. And it's a pity -- for the nation as well as for the families of the soldiers who were killed during the four subsequent years of the war (nearly a third of all Americans killed in Vietnam) that the son of a bitch didn't swing for it.

This is a revelation that diminishes even Watergate. And it may lead someday to the book that has yet to be written about the farcical notion of Nixon as a master of foreign policy. This was Nixon's foreign policy: prolonging Vietnam and illegally expanding it into Laos and Cambodia, not to mention his support for the Greek military junta and his almost-certain support for the CIA-backed coup that installed Pinochet in Chile. Someone may even ask what no one has asked about what is still regarded as Nixon's indisputable moment of glory: his opening of relations with China. If China has been opened to the West, why does it now routinely ignore, even refuse to consider, the complaints of Western governments?

Nixon's real legacy is the cynicism toward government that has become a mainstay of American political discourse since Watergate. Even Summers ends the book by saying "Because of what they learned at Watergate, Americans are perhaps less ready to trust blindly in their leaders ... The downside, however, is that Richard Nixon's abuses and deceptions may have led many citizens not to trust their leaders at all."

It didn't have to be so. Post-Watergate cynicism has become such an accepted part of life for more than a quarter-century now that it's easy to forget the exhilaration of Watergate itself. Mary McCarthy compared it to a national town meeting. As McCarthy wrote, "Everybody has been fully participating, and nobody, in principle, given the equality of opportunity available, is more of an expert than the next person." That's a definition of the democratic ideal, people behaving as if the fate of the republic depends on their participation.

So the cynicism that resulted is immeasurably sad. And it must be said that the press has to bear some responsibility. Watergate elevated the investigative reporter to almost mythic status, but the reporting that followed has often shown an inability to distinguish between nefarious acts that are truly newsworthy and the minutiae of everyday corruption. That's why the accusations of wife beating in Summers' book are getting the most coverage. The logical conclusion of that kind of scandalmongering is to treat Whitewater and Monicagate as if they were serious stories.

Clinton's impeachment saga was the negative image of Watergate, not only in its demonstration that the democratic process could be used to subvert the very meaning of democracy, but in the spectacle of a press corps so hungry for dirt that they failed to do their job as reporters. We have gone from the Washington Post bravely backing Woodward and Bernstein when few other press outlets cared about Watergate, to the Post's Susan Schmidt running unchecked allegations that were probably leaks from Kenneth Starr's office.

Summers trades a little bit in this with his reports of Nixon's wife beating and drug abuse. But he is blessed with a sense of proportion. He knows where the real story lies. In detailing his findings, I have perhaps given short shrift to the verifications he provides. Some of these allegations may never be nailed down beyond all doubt. But that doesn't mean that Summers is trafficking in a type of journalism he disdains, in which vague connections are offered as proof of guilt. There is a world of difference in triangulating responsibility based on chains of commands and who met with whom on what dates, on making reasonable, substantiated supposition, and spinning conspiracy yarns.

But even if Summers were an unscrupulous journalist, what could he or anyone else possibly do to defame Richard Nixon? What obscene fantasy could make Nixon's hands any more blood-stained, his mind any more a cesspool of deviousness and prejudice, his actions any more the product of conscienceless cunning? Summers' book is an example of how the revelations of investigative journalism can awaken rather than inure. It suggests that to be wary of Nixon's ability to rise again and again and again, even from the dead, is a form of patriotism. We haven't seen the last of Dick Nixon. And we should be waiting with garlic and crosses -- and most of all the stake.

Shares