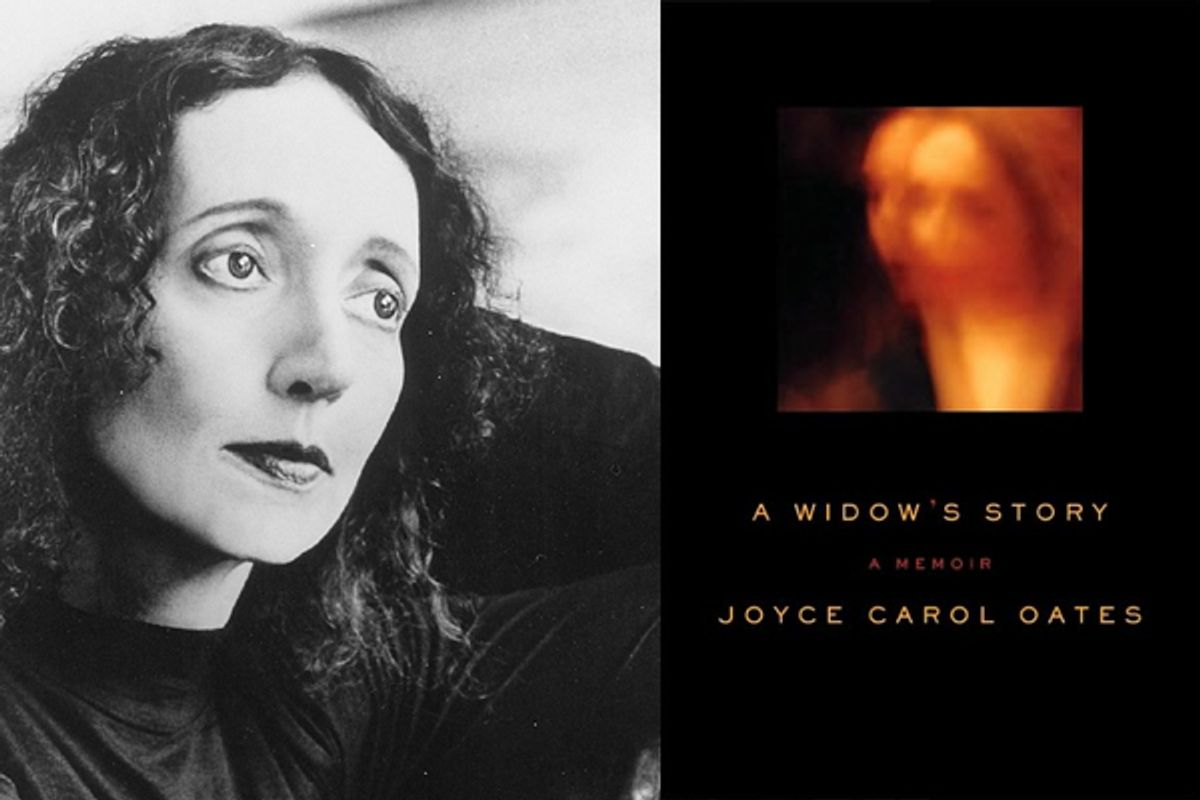

The prolific author Joyce Carol Oates has written a book about losing her husband, following in the heartbroken footsteps of many other such memoirs, such as "The Year of Magical Thinking" by Joan Didion. Oates' book, "A Widow's Story," has been generally, although carefully, praised save for one review by New York Times critic Janet Maslin, who (bravely or foolishly, take your pick) questions the author's sincerity of purpose.

Maslin is careful not to criticize Oates' grief process but rather takes aim at the lack of emotional meaning or depth in "A Widow's Story." Oates' book is "far less fastidious ... flabbier and flightier" than Didion's work, Maslin asserts, and includes "threadbare metaphysics ... much minutiae ... and worrisome signs of haste." She also finds Oates' selective retelling to be deceptive. For example, the author includes poignant and poignantly funny stories about grieving but fails to go deeply into her 47-year marriage. A far more grievous omission, in Maslin's view, is the fact that Oates became engaged 11 months after her husband died and is now happily (one hopes) married. "How delicately must we tread around this situation?" Maslin asks. All of this leads her to conclude that Oates may have been seeking to "willfully [tap] into the increasingly lucrative loss-of-spouse market."

Full stop.

It's hard for me to distance myself from these memoirs -- as a writer or as a widow. My first reaction is almost always a distressing cocktail of anger, despair, envy and confusion.

The writer in me asks: How did there come to be a subset of memoir about spousal loss? How do we rate and rank these books? How do we rate or rank the loss? Are those with greater command of the language or the market share the ones who are most "qualified" to write about this subject? Does it depend on circumstance, or on context? Was my experience with grief and mourning worthy of a share of that "lucrative loss-of-spouse market," even though I was told way back in 2001 that the story of a middle-aged childless widow was far less compelling than that of a young mother of three whose husband had (also) died in the 9/11 attacks?

The widow in me wonders: How long?

The Oates book and Maslin's review have generated a fair amount of blogosphere discussion about the grieving process. Author Ruth Conigsberg insisted that "these memoirs are ... highly subjective snapshots that don't teach us much about how we typically grieve, nor more importantly, for how long." Conigsberg, it should be noted, has her own book concerning the myth of the stages of grief.

She notes optimistically that many older people do recover from losing a spouse to natural causes fairly quickly and even remarry, as did Oates. Her findings are not to be confused with studies that show younger people who lose their spouses in traumatic situations and remain widows or widowers are six times more likely to experience dementia.

Uh-oh.

Nine and a half years after my traumatic loss, I float in a sea of doubt. I don't even know if I'm still grieving or if something else is at play. Was my marriage at 40 an anomaly, a one-time event? The more time that passes, the more I circle back to "before" -- before I met the man I would marry; the years spent in the company of inappropriate, uninterested, noncommittal men while yearning for the comfort of a stable relationship. I spent, will have spent, will spend, more years alone than in a romantic partnership. The marriage, as joyful, as sustained, as relieved and as (foolish me) safe as it made me feel, was a blip on the radar screen of my life, an accident of fate. I float, I coast and I wonder how I can draw any kind of illustrative, instructive or illuminating lessons from the before, the "during" or the after.

The writer in me thinks: Oates is a well-known, well-respected writer and professor at Princeton University. She's out there. It might have been more, what, helpful to let us know her process included finding happiness again so quickly. Then again, she wasn't necessarily writing a self-help book, just an accounting.

The widow in me understands: Any memoir I write would be so unresolved as to be thoroughly unsatisfactory, even to me.

Shares