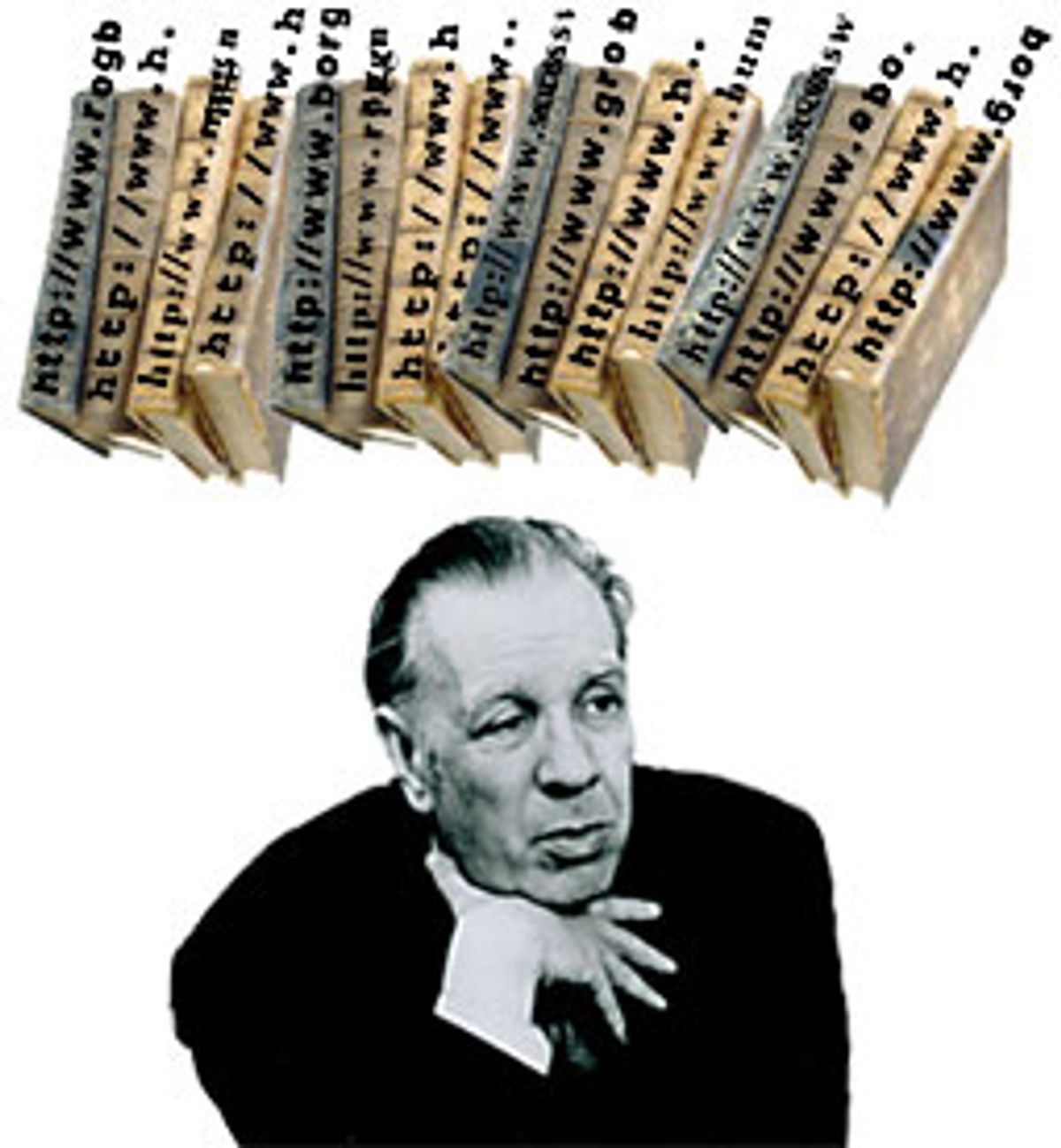

It was Borges, Borges himself, who provided the key. Once I discovered it, of course, I realized that the clues are everywhere in the three volumes of the great Argentine writer's collected works recently published -- on the occasion of his centenary and in new English translations -- by Viking Press. Borges was fascinated by the idea of a hidden truth only accessible to the most dedicated reader; for instance, in a 1938 book review, and again in 1941's "A Study of the Works of Herbert Quain," he proposes a mystery novel whose true solution is not the one presented by the detective, but hinted at by a single casual phrase. It was in the story "Pierre Menard, Author of the 'Quixote,'" that I found just such a phrase, a tip-off that the greatest inspiration for Borges' work was a phenomenon that wasn't invented until four years after his death in 1986: the World Wide Web.

Borges writes that his fictional author "has (perhaps unwittingly) enriched the slow and rudimentary art of reading by means of a new technique -- the technique of deliberate anachronism and fallacious attribution. That technique, requiring infinite patience and concentration ... fills the calmest books with adventure." Of course! Nothing could be more Borgesian than ignoring linear time; in the meticulously perverse logic of his stories, essays and poems, it's only natural that an author would be influenced by events yet to occur. With the patience and concentration Borges demands, it can be seen that his understanding of the Internet was absolute -- we who are merely its contemporaries can't possibly enjoy his perspective. And reading Borges' cryptic, deadpan paradoxes as commentary on the wired world does, indeed, deliver a jolt of recognition.

I am not the first to point out that Borges' great invention, the Library of Babel, that immense, honeycombed labyrinth containing every possible text -- true, false and gibberish -- is a fanciful metaphor for the Web. As we become more familiar with the Internet's applications and idiosyncracies, the parallels planted in Borges' work become more clear. What are the "infinite stories, infinitely branching" of his character Herbert Quain's book "April March," if not hypertext? What is the purpose of Ireneo Funes, the paralyzed young man unable to forget any aspect of anything he has ever seen, if he is not to represent search engines burdened with memories of long-inactive links? What is Tlvn, the virtual world in "Tlvn, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" that gradually overtakes the real one, if not the cyberspace for which the physical world is rapidly becoming a quaintly antiquated sketch?

Canny Borges never names the Web, of course: As "The Garden of Forking Paths" points out, in a riddle whose answer is chess, the only word that cannot be used is "chess." But the meaning of his parables is specific and undeniable. The Aleph in the fiction of the same title, the portal through which one can see every point in the universe, is Netscape Navigator in all but name. The Zahir, an object that changes its form over time but monopolizes its owner's attention forever, is none other than Microsoft Internet Explorer, as anyone who's tried to unstick it from a computer's operating system only to click fatally on an innocuous icon will tell you. (Consider, in fact, the alphabetical remove of Borges' names for the browsers, his subtle jest on the Alpha and Omega of his new world.)

"The Lottery In Babylon" -- in which all people in a society change their stations constantly, power and wealth springing up instantly and evaporating immediately, in ways dictated by blind chance -- is an idle fantasy if one ascribes no other meaning to it. Read as Borges no doubt intended, as a precise allegory of the dot-com IPO market and internal Web commerce, it becomes a scathing satire, and far more severe and elegant.

For that matter, Borges' fictions, poems and articles are liberally hyperlinked to each other: His motifs of labyrinths and tigers and Dante appear again and again, coyly alluding to their sister pages. The learned allusions he loved so well are links to outside pages; it is one of his finest jokes that his reviews of imaginary volumes and quotations from imaginary authors are, quite simply, dead links. It's not yet certain what relevance all of Borges' works have to the Web, of course; it's too new a technology for some of his meanings to become clear. I look forward, for instance, to the events that will allow us to fully comprehend "The South," the curious tale of a traveler who gets in a knife fight, the tale that Borges thought might be his best story. "It is possible to read it both as a forthright narration of novelistic events and in quite another way, as well," he introduced it, practically shouting for it to receive an interpretation that can only be revealed as the Web evolves.

Through Borges' technique of anachronism, we can see the real meanings of other authors' work as well. Anne Rice's "Interview With the Vampire" is a darkly wry, knowing discourse on AIDS, a disease unknown at the time of its publication. Mikhail Bulgakov's "The Master and Margarita" is far more convincing as a commentary on post-Soviet Russia than as a fantasia of the Soviet era in which it was composed. I am reliably informed that the hidden purpose of one of Rex Stout's sturdy detective novels (the title escapes me), concerning orchid-sniffing detective Nero Wolfe, unfolded (orchid-like itself) only recently when it was revealed to be a commentary on certain private machinations at a large software company. It is possible that every book contains within itself a second, secret book, whose true meaning is invisible to its contemporary readers and even (perhaps) its author.

Postscript: After several weeks of considering Borges' commentary on the Web, I am obsessed by it, like the Zahir; its hold on me is stronger than the hold Microsoft has on my hard drive. I am filled with trembling at the thought of his revelations -- not waiting for them to "come true," but waiting to understand their truth. As Borges' greatest and most invisible labyrinth expands around me, I can console myself only with his words, fittingly also from "Pierre Menard": "There is no intellectual exercise that is not ultimately pointless."

Shares