Sam the Cat and Other Stories

By Matthew Klam

Random House, 243 pages

The Sleepover Artist

By Thomas Beller

Norton, 296 pages

Venus Drive

By Sam Lipsyte

Open City Books, 160 pages

Never Mind Nirvana

By Mark Lindquist

Villard, 239 pages

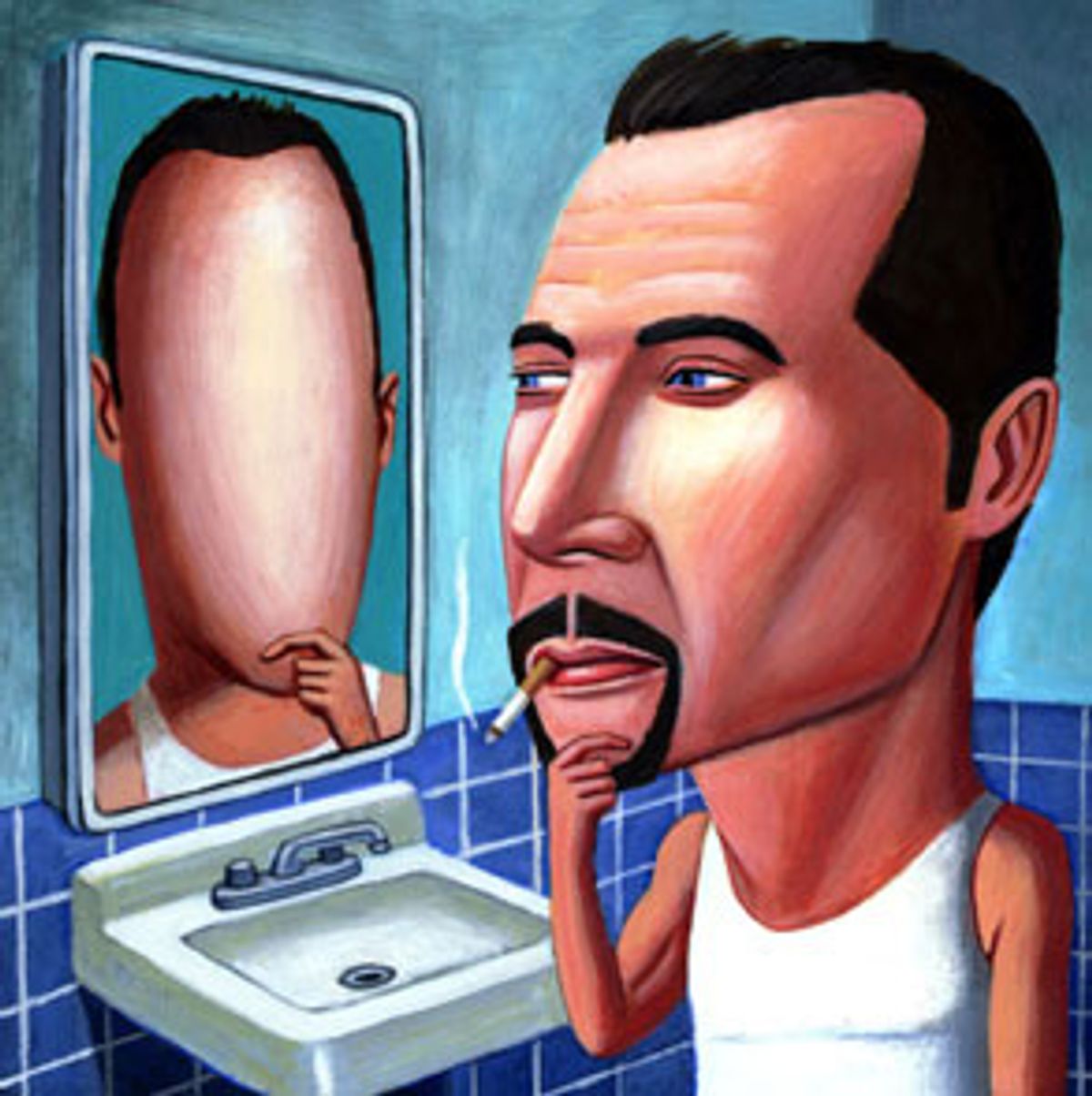

In case you're wondering what to expect from a book called "Sam the Cat and Other Stories," the cover of Matthew Klam's first book provides a helpful clue: It's a photo of a guy's crotch with the book's title laid out to form an erect penis and the curve of a scrotum below. With its promise of daring but fizzy fun in a masculine package, the cover suggests that publishers, having exhausted the possibilities of "Bridget Jones"-style "chick lit," have decided to give the guys a shot.

And, in fact, there are several books out this season that plow territory similar to Klam's, including Thomas Beller's "The Sleepover Artist," Mark Lindquist's "Never Mind Nirvana" and Sam Lipsyte's "Venus Drive." All, like "Sam the Cat," concern white guys in their 20s and 30s; they're often urban, and they're usually single, with an unsettled quality to their lives. The characters vary in their class backgrounds and in the fanciness of their educations, but they all seem to feel emasculated by the girlified rituals of dating, relating and marrying, as well as by the difficulty of finding their place in the can-do, go-go boom economy.

But sadly for those who would like to see a revival of fiction about (and primarily for) men, these publishers' efforts are doomed. Forget the attention-grabbing cover: Klam's book is a perfect example of how and why most of the current crop of guy fiction fails to create compelling -- or marketable -- literary characters.

Since popular opinion often states that men (at least, or especially, the American variety) are basically inarticulate about their feelings, the job of the writer who takes them as a subject is to find something emotionally legible in their lack of apparent interest in their own deepest selves. This can produce, paradoxically, writing that's far from shallow. Richard Ford, to give just one example, has turned the American male resistance to self-examination into a vital and resonant theme. And, of course, Hemingway at his best managed to convey a male inner life without actually getting in there and poking around too much. As he once said, his writing was like an iceberg, showing you only the visible tip, while the huge mass of emotions lay concealed beneath the surface.

But Klam and his fellow guy authors are writing characters who grew up in a post-therapy, post-Venus-and-Mars world. If they don't talk about their feelings, at least they know they're supposed to; "Issues I Dealt With in Therapy" is the title of one story by Klam. His stories are almost all written as first-person confessionals. In a revved-up everyday-guy language that at times feels exhilaratingly original, his narrators tell us how they feel about their girlfriends and wives, their sex lives, their jobs, their fathers. They talk about themselves a lot, often analyzing their own personalities with a surprising honesty: "I've been a certain way my whole life," says the narrator of "Not This." "Mr. Showcase, Mr. Jokey, Mr. Handshake. After a while, even I can't stand it. I look down on people. I've got a short fuse. I piss on my friends."

But what, exactly, does this self-knowledge serve? In story after story, it stops at the point where it might open out to new kinds of understanding about why a character has ended up where he is or about the choices facing him in the future. It's the reverse of Hemingway and Ford: Instead of very little talking that manages to reveal a deep self, there's a lot of talking about a very shallow self. Instead of the strong, silent type we get the smug, garrulous type.

The narrator of "Not This," for example, doesn't grow or change over the course of the story; he merely settles deeper into a defeatist slump over the fact that, after his latest quasi-violent outburst, his on-and-off girlfriend -- "the best-looking, the smartest, the best dressed" he's ever had -- has left him for good. Klam's characters don't experience emotional transformation, and in this way the book subverts one of the basic components of fiction: The stories have no turning points, no real epiphanies. That in itself might be a kind of epiphany -- I supposed the idea would be that much of life is really just the same old thing -- but it's not a particularly promising one, and it's certainly not worthy of the seven story-length variations on it that "Sam the Cat" comprises.

Even more insidious is the sneaky suggestion in these stories that everyone is just like these characters, just as unwilling or unable to move on emotionally, to try out new ways of seeing themselves or of interacting with other people. Klam himself, in an interview in the Washington Post, lays out his small-minded credo as if it's a universal truth: "One ought to be reflective," he told the interviewer. "And what does it get you? It gets you nothin'. Ultimately, you know you're neurotic. It's better than being a drug addict, I guess."

In the typical Klam story, a crucial piece of self-knowledge hovers just out of the narrator's reach. Usually, it's something that, if he said it out loud, might lead him to a new understanding of himself or of why his life is the way it is. It might even lead him to make some changes. But Klam's narrators don't change anything; for all their masculine talk, they are essentially passive and spineless, constantly flummoxed by the hand the world deals them.

"Linda's Daddy's Loaded" is a representative story in this vein. Its married, SUV-driving suburban-guy narrator recounts a visit from his wife's obnoxious father, whose gifts of money the couple has used to purchase an "awesome lifestyle"; the insecure and depressed Linda has "retired." The father arrives, spewing insults and condescension, and Linda teeters on the verge of a breakdown. The narrator is so stressed by it all that he makes a nasty remark to Linda, which he later regrets: "I think of that mean thing I said to Linda -- what was that all about?" But when Linda's father promises to hook him up with a fancier job than the one he's got, he takes him up on it.

The story, which presents us with what looks like a slow-motion family train wreck in the making, does register the narrator's ambivalence, but it ends on an up note, as he reassures himself, and us, that it will all work out OK: "We're going to be happy more than not, Linda and me. Even when it backfires, you don't necessarily hate someone for that long."

Is Klam being ironic? I don't think so. A riff like this one conveys a sort of quasi-ironic realism -- it captures something of how life is often experienced: Our best relationships are more or less filled with conflicting emotions. But Klam's stance also seems designed to hide the fact that as an author he has nothing transformative to say. He can't seem to imagine that there might be an alternative way for his characters to see themselves.

That the narrator of "Linda's Daddy's Loaded" is a bafflement even to himself seems to be one of Klam's central points, but the story has no point of view on the colossal -- you might even say tragic -- self-delusion at its heart: This guy has sold himself to his sleazy, tyrannical father-in-law. Like the narrator of "Not This," he seems to have chosen his beautiful but emotionally damaged wife as though she were a prom date: "The second I met Linda, I knew she was the one," he says. "She was way better looking than anyone I'd ever dated before." In other words, he has been led by his dick, but neither he nor his dick is getting the last laugh.

This guy, in short, is not the captain of his own fate. Maybe he and Linda will be "happy more than not," maybe not, but surely there will be grim consequences to the passivity, bad judgment and denial that's gotten him to this point. Klam seems compelled to protect his characters from the most difficult kinds of self-knowledge, and the result is that they read as interchangeable examples of a type -- the well-meaning but clueless regular guy -- rather than as complex human beings facing their individual destinies. He's too easy on them; he's an author who pulls the bandages off his characters' wounds, then holds them up for Mommy to kiss.

Part of the deal when an author presents unformed characters is that we may develop affection for them, but we also have to not like them a little -- they have to not like themselves a little -- or they will never grow. From Emma Woodhouse to Holden Caulfield, that's a literary principle that's apparently lost on Klam. His characters are dying for us to like them. And while they may say they hate certain aspects of themselves, what they really don't like is the trouble they get into because of those traits. Klam tries to get away with this literary sleight of hand by ending many of his stories in the false glow of a narrow escape from the sort of situation that is bound to recur, since we've seen no evidence of newly developed insight or self-knowledge.

Thomas Beller's "The Sleepover Artist" is a similar exercise in self-knowledge that goes nowhere. Like much current dude literature, this collection of linked short stories harbors a deep suspicion of the urge to improve things. Even in grade school, Alex Fader, the central character, has noticed and begun to be bothered by this feminine trait: "His mother was always, as far as he could tell, trying to make things nice," says Beller's narrator. "It was tiring."

At first, this theme seems like a clever salvo in the gender wars. It's true, of course, that manic self-monitoring and a fussbudgety drive toward personal betterment can be soul-depleting habits. But as Beller walks us through a decade or so of Alex's relationships, always paying impeccable attention to the nuances of Alex's feelings (except for a few forays into the points of view of Alex's girlfriends, in which Beller reveals to us their feelings ... about Alex), it begins to seem as if Alex's stance against forced self-improvement is a convenient mask for his inertia.

It's hardly compelling literary material, Alex's journey toward the recognition that to live well requires figuring out when it's time to change. The final scene of "The Sleepover Artist" has him, now 30ish, talking to his mother about a battle raging in her co-op apartment building over the installation of new windows. "Some changes are worth resisting," she says, and when Alex asks which ones she answers, "You'll have to find out for yourself." That's the end of the book; it would have been more trenchant as a beginning.

It's not that it's impossible to do interesting things with the emotional paralysis of men in their 20s and 30s who feel simultaneously jerked around and abandoned by their culture. Sam Lipsyte's "Venus Drive" is a more cogent treatment of this same theme, in part because, unlike Klam and Beller, Lipsyte manages to write in the first person while subtly directing our attention outside his characters' heads, to the forces around them that shape their predicaments. Lipsyte is most impressive as a stylist -- these stories are written in a wonderfully allusive, refracted language -- but he also looks head-on at the quandaries of people who understand their destructive patterns but don't want to change them.

Lipsyte is aware that part of the reason life continually defeats his characters is that they shy away from hard truths about themselves. His people tend to be losers and outcasts -- guys with drug problems, guys who can barely hold down a job, guys who spend a lot of time at peep shows -- and yet his stories lack the defeatism and easy self-reassurance of Klam's and Beller's.

Often, Lipsyte's characters' very strategies for evading self-examination slyly serve as a way to be honest about their lives. In "Less Tar," for example, the narrator explains why he didn't quit smoking when he was in drug rehab: "You have to keep something between yourself and the truth of yourself or you're dead, was how I figured it. Still do." This is a character who knows his own depths, loath as he is to spend time hanging out with them. He's not asking us to feel sorry for him or believe the lies he tells himself.

Still, even Lipsyte's stories give the impression that emotional stasis has become a point of honor for dude fiction. It's as if to try to change for the better would be to give in to women -- which leaves male characters waging a petty and self-defeating battle indeed. Over on the girls' fiction side, by contrast, the relentless drive for self-improvement is practically a plot requirement. It's no coincidence that Helen Fielding's sequel to "Bridget Jones' Diary" is an outright satire of the self-help genre, while Melissa Bank's bestselling "The Girls' Guide to Hunting and Fishing" presents itself as a sendup of and rebuttal to self-help books.

These books satirize self-help, however, only in the most gentle, conservative ways. "Girls' Guide," for example, merely substitutes a different kind of getting-a-guy advice for the retro model hawked in books like "The Rules." Bridget and Jane (the heroine of "Girls' Guide"), like the kind of girl who spends her free time reading about them, often seem to be on a mission to fix themselves and improve their lives (though it's debatable whether they actually do change in substantive ways). And there we have the secret to these books' success, if not as literature, then at least as moneymakers: Bridget herself would undoubtedly buy "Bridget Jones' Diary"; Jane would be first in line to purchase "The Girls' Guide." These characters, in fact, are often depicted reading. There's a self-perpetuating cycle at work: There are people out there who not only identify with Bridget (and Jane) but also buy books. The urge toward self-improvement, after all, has always been bound up in the act of reading.

Would a character in a dude lit book ever read a dude lit book? It's doubtful. Even the relatively genteel Alex Fader, I suspect, would read magazines but not novels, especially since Beller's made his alter-ego a budding filmmaker. (If he were a fiction writer, he'd naturally need to be constantly sizing up his rival novelists; reading would then be attractive as a competitive outlet.)

Perhaps the death knell of the nascent genre sounds on the very first page of Mark Lindquist's "Never Mind Nirvana," which in its determined lightheartedness comes closest of these four books to "Bridget Jones' Diary." Pete Tyler, having just turned 36, is sitting at home assaying a copy of that bible of male disaffection, Richard Ford's "The Sportswriter":

After a few minutes Pete becomes restless. He wants to at least finish a chapter, but he thumbs forward and determines there are 17 pages left, too many. He abandons Mr. Ford for the company of Johnny Walker.

Shares