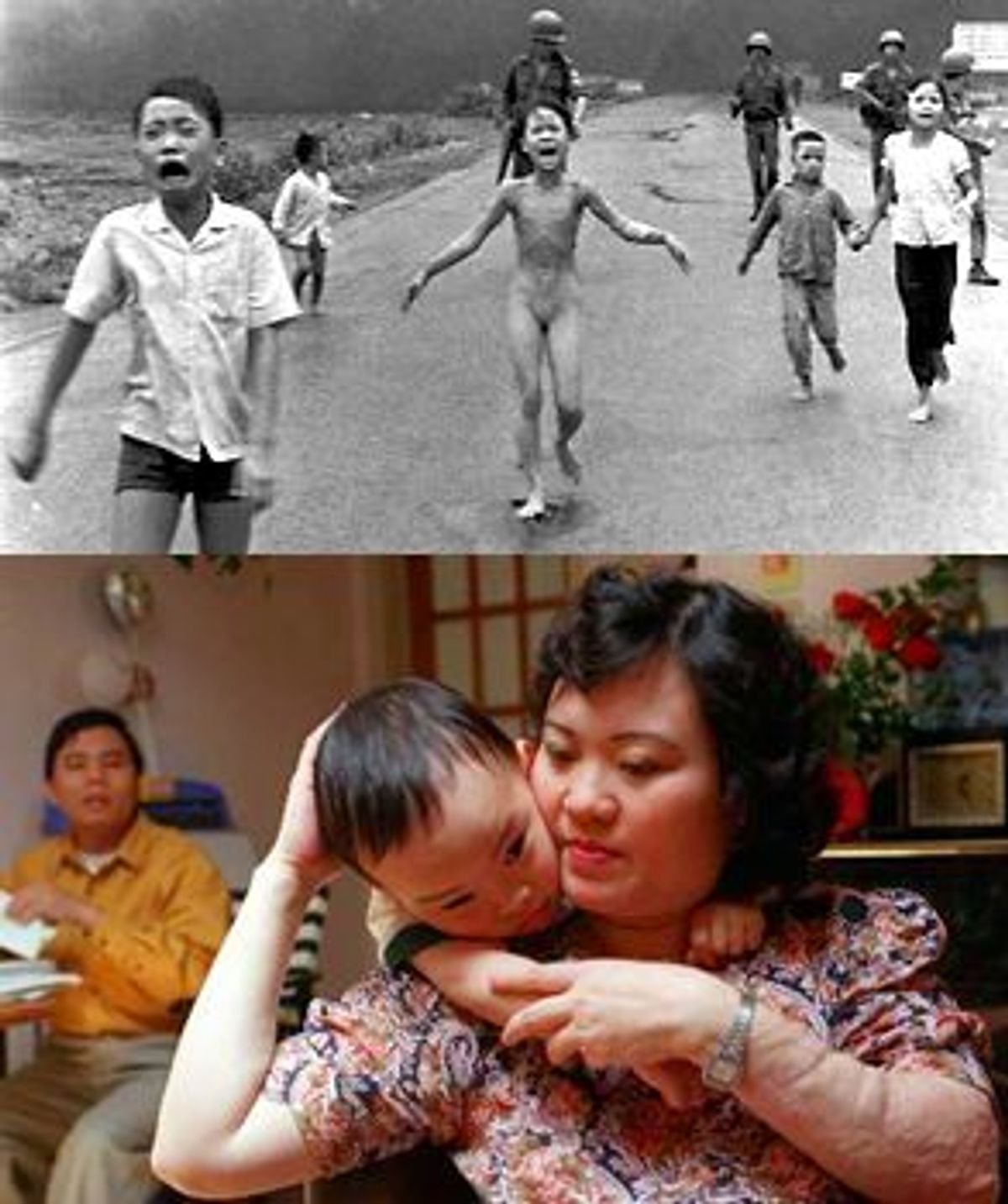

On the morning of June 8, 1972, "fire rained from the sky" onto Highway 1 outside the South Vietnamese village of Trang Bang. Seared by napalm, dazed by the bomb's impact, 9-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc picked herself up, tore off her clothes and staggered down the road. Associated Press photographer Nick Ut's picture of Kim -- mouth agape with terror and pain, arms splayed out from her small naked body -- became one of the most enduring and horrific images from the Vietnam War.

In her new book, "The Girl in the Picture: The Story of Kim Phuc and the Photograph That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War," Canadian journalist Denise Chong chronicles Kim Phuc's life before and after the devastation captured on film. Kim Phuc would have to recover not only from her terrible burns, but eventually from her own fame as well. The Communist regime's relentless manipulation of her as propaganda material frustrated her attempts to live a "normal" life. She was sent first to the Soviet Union, then Germany, finally to Cuba. On return to Cuba from a honeymoon trip to Moscow, Kim and her husband defected to Canada, where they live today with their two children.

Denise Chong trained as an economist and worked as a senior economic advisor for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau until 1984. She is the author of the much-praised family memoir, "The Concubine's Children."

We look at the image of Kim running from the napalm attack and we're horrified. We think, "What can I do?" In John Berger's essay "Photographs of Agony," he writes that when we view shocking war photographs our response "is bound to be felt as inadequate." By writing this book, you pushed well beyond that response.

Yes, but you can't underestimate the power of this photograph. I had it on my wall for years and then finally I had absorbed it enough that I could take it off the wall and finish my writing. The power is that it makes you look inside yourself. And when you look inside, you realize it all comes back to the idea of human failing and the angst of human inadequacy.

What gave you the idea of pursuing this story?

It literally fell into my lap.

How so?

"The Concubine's Children" was just out, and I was considering what I would write about next. Out of the blue, I got a call from my publisher. It had been hush-hush until that point that Kim was in Canada, that Kim was in the West at all. She was then in such desperate straits -- her husband was scavenging through garbage for baby furniture -- that she decided she'd sell her story. So she made the deal with my publisher who then came to me. What surprised my publisher was that I didn't say yes immediately.

Why was that?

Having written my family memoir, I'd begun to understand the tool and the power of memory. I wondered if this tool was going to work in this case. Memory is so flawed. Kim was a child when this happened. War is traumatic. Memory's under assault. I thought I'd have to meet her several times, to see if there was a trust.

What were those first meetings like?

I had to be clandestine about my meetings with Kim. I hadn't concluded the deal, and my publisher didn't want any competing bids. It was very quiet. Here was someone who was paranoid about the media and still afraid of the regime [in Vietnam], and I almost felt I was a stalker myself. Then that shaped my whole idea that this was a victim of war. This is what war does: It makes victims. Is there any other fate for her?

By the end of the story, she's moved beyond being a victim of war and that's what's so satisfying to see. Do you think the book has helped facilitate that?

I think the book was enormously helpful to her.

In shaping her memory?

Yes. When Kim read the manuscript for the first time, she just said, "It's not true. It just can't be true." But of course I had it all on tape from the interviews in Vietnam. She knew so little about the war! You know, the closer you are to war, the less you know what's going on. When she started to see those pieces around her, it eased her own idea of how much she had suffered, because she saw how others had suffered as well. She couldn't believe how much her mother had suffered. She hadn't been aware of that. She hadn't been aware of how her family had been pulled apart during the war, and she did refuse to believe it at first, even though clearly I had the interviews.

To the right of Kim in the photo are soldiers and some of the photographers. It's odd to me that their body posture is so relaxed and the running terrified children are under such incredible stress. The children and the photographers are having such a different experience of the same moment.

Yes, it flashes by them. Not until those journalists see that picture on the wire do they realize that, out of that day, this is what will be remembered. Even seasoned journalists like [New York Times reporter] Fox Butterfield did not foresee that. He didn't mention Kim in his story.

Did Nick Ut [who won a Pulitzer for the photo] know when he took the photo how extraordinary it was?

The image that Nick is left with is the whole sequence -- it burns in his mind the color of the napalm. That's what he cannot forget. When I talked to him, he cannot forget. All that he sees is the red of the napalm. He has none of that "coming to terms" that Kim has had.

Why do you think that is?

This is the peculiarity of the picture itself turning Kim into an icon of war. And she has to reconcile herself to that, come to terms with that status. There is no similar process for others involved with that picture.

Were Kim's parents and relatives hesitant to talk to you in Vietnam?

No! And this again made me steel my nerves to say, "This story has to be told." Because it was very dangerous for them to meet me in Vietnam. Although I took care with the meeting times and places and kept on the move, I always made sure that we met in windowless rooms. It was brave of them to meet me. Although they've been living in silence and keeping their heads down for all these years, they want to tell.

You really slow down everything around the moment of the bombing that wounded Kim. You round out everyone's perspective, from Kim to the photographer to the nurse in the burn ward -- seeing it omnisciently, in a way the people involved in the incident can't.

I did this very deliberately.

There's so much in that description to absorb. I'd always thought it was American planes that had dropped those bombs. I was surprised to read they'd been dropped by South Vietnamese planes.

That's very understandable, because America introduced the horror of that weapon into the Vietnam War and put it to widespread use. When Kim Phuc defected to the West [in 1992] the Vietnamese regime was very bitter because it was the Americans who had made the napalm.

Even though they were South Vietnamese planes, were the strikes still ordered by Americans? I was unclear on that.

Yes, I was deliberately unclear on that. Because of course I couldn't get to the bottom without digging up Pentagon records.

The Americans were very thin on the ground at that point ... and this was a very localized airstrike, but the point I tried to establish with John Plummer [the captain whose job was to coordinate air support under joint American and South Vietnamese military command] ... again you're returning to looking at that picture and the torment that end of war brings, the torment that doesn't ease. When people like John Plummer look at that picture, they see inside themselves ... and out comes guilt. It doesn't matter that it was South Vietnamese planes and that it wasn't a direct operation. It's guilt that they can taste. And that torments him.

I included Plummer in the book because I think it's important. It doesn't matter that I wasn't able to dig through all the Pentagon records to establish whether he was exactly in that chain of command.

It's more about what's in his mind?

Yes. I'll tell you another example of that guilt. I had hours of conversation with a helicopter pilot who described how he alighted on the Highway Route 1 [where the incident happened] and picked up the burn victims, and picked up Kim and took her to a field hospital. He had it in exact detail: the village, the attack, the aerial view of the village. This was hours of conversation. I saved my important question for the very end. I asked him when he served in Vietnam. And it doesn't overlap. It's guilt, you see. He's tormented. The picture provokes that ... it doesn't have to be personal, it can be a sense of collective guilt. It doesn't matter whether it's "your" war, or "our" war, because it's what one human being does to another.

You came of age in Vancouver, British Columbia, during the Vietnam War years. Were young Canadians outraged about what America was doing in Southeast Asia?

It didn't rip apart the social fabric in the same way as it did in the United States. There was a sense of relief that it wasn't "our" war, though I've read stories about Canadian companies sending munitions through American companies.

Did you see the photo when it first came out?

Oh yes, yes.

I wonder if your being Canadian allows you to tell the story and let the facts and images speak for themselves. I wonder if that would have been harder for an American to do.

I've often thought that. It's still so palpable: the feeling of the war, the horror of it, the loss and the tragedy and those who are still tormented by nightmares of it. It's hard, therefore, not to want to look inward or outward for blame. Even just discussing the war, when there's an American in the crowd, the discussion takes on a rawer passion.

Both you and [veteran New York Times correspondent] Henry Kamm make the point that to most Westerners, Vietnam is a war, not a country.

After the moment when that helicopter lifts off from the rooftop of the American Embassy [in Saigon], Vietnam just slips below the radar screen.

In Kamm's recent book "Dragon Ascending," he notes that those who felt anguished for what the Vietnamese had gone through during the war were "strangely silent during the next period of their suffering when hundreds of thousands felt their best choice was to entrust their lives and those of their children to tiny, unseaworthy boats on the treacherous South China Sea." We did see those pictures of the boat people, but we didn't have much information about what life was like in postwar Vietnam.

It's rare in daily news coverage that you go in afterwards and examine the havoc that the end of war brings. The picture of Kim comes late in the war, although people often think it comes earlier. American public opinion had already crystallized at that point. They just wanted the war to end. You can document the exact hour and minute when the war does end with the helicopter lifting off, but the torment of war doesn't end so easily.

Note: In 1997, UNESCO appointed Kim Phuc a goodwill ambassador "to spread a message of the need for reconciliation, mutual understanding, dialogue, and negotiation to replace confrontation and violence." Kim Phuc has also established a foundation to help child victims of war.

Shares