The sixteen-year-old clawed away at bodies, pulling aside arms and legs to hide herself beneath the dead. "I could hear blood flowing down, the sound of blood gurgling out of the bodies," she remembered. Her throat was burning; she gulped down what she found on the floor. "I drank like a mad person ... The horrible thing was that blood kept flowing down from the bodies above me. So I couldn't really tell whether I drank blood or water."

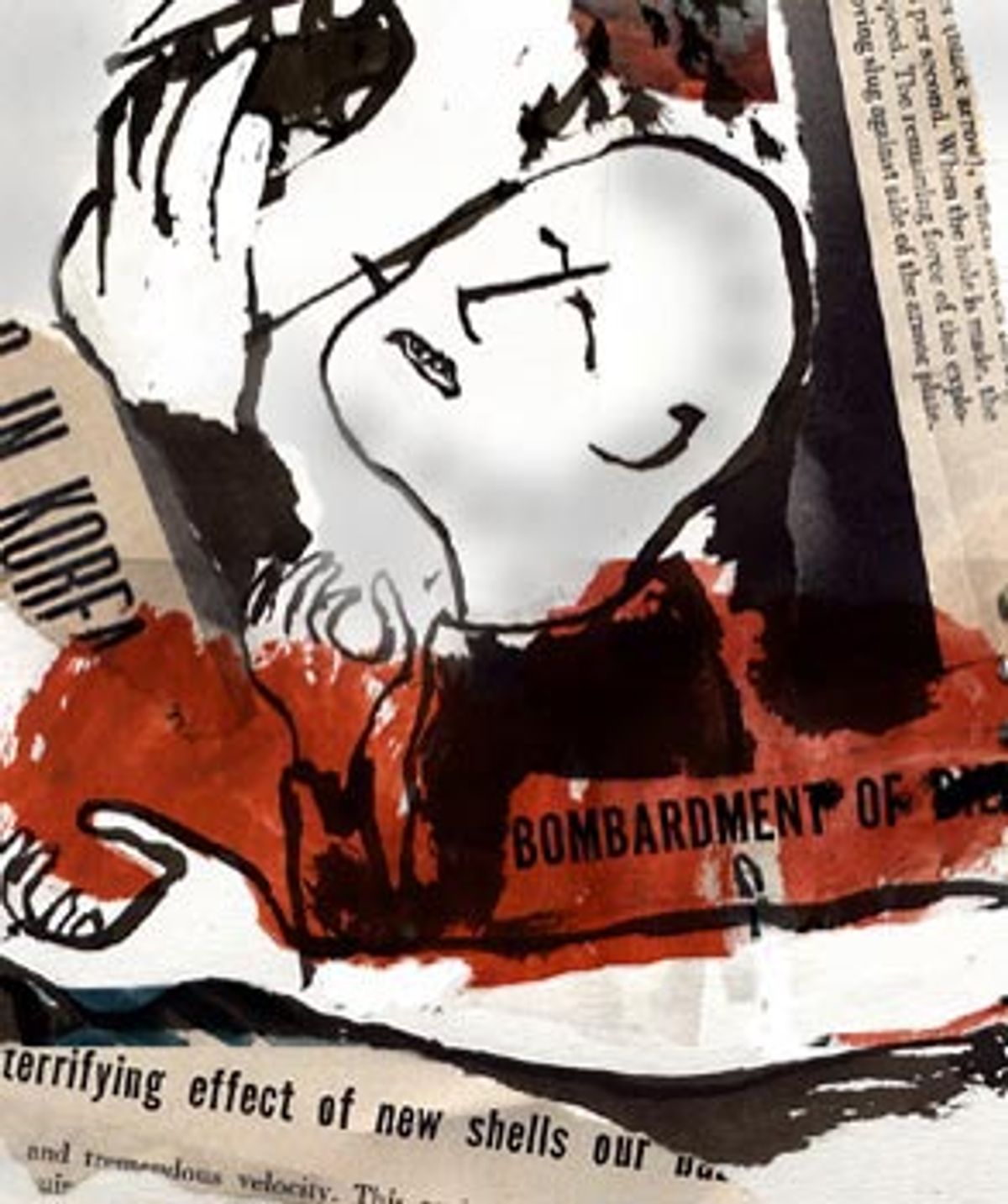

There are a lot of ways to tell the story of human warfare, and each will tend to give us a different view of when, how and why we should go to war. One way, almost guaranteed to make a knee-jerk anti-war activist out of any reader, is the personal, face-down-in-the-dirt testimonial, like that quoted above, of Park Hee-Sook, a bewildered South Korean refugee featured in "The Bridge at No Gun Ri" by Charles J. Hanley, Sang-Hun Chose and Martha Mendoza. In July 1950 Hee-sook was forced out of her home by American soldiers, strafed and rocketed by American aircraft on the road she was directed to take and then pinned down by American sniper fire under a concrete railroad trestle for three days amidst the bodies of her dead and dying family and friends.

Another way to frame the narrative of war is by rational analysis -- or rationalization -- of the factors that lead to success or failure in combat. This kind of treatment flings aside the question of why or whether war should be initiated, and concentrates instead on how it is won. Military historian Victor Davis Hanson, in his new book "Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power," gives us the vulture's eye view: vast panoramas of hacked, charred, and waterlogged bodies are essentially abstracted to putrefying rectangles on battlefield maps, picked over to illustrate the clear superiority of Western cultural values when it comes to the prosecution of successful bloodbaths.

Hanson's view in "Carnage and Culture" is grim but elevated, because he claims to believe that Western military dominance has nothing to do with morality. Instead, he insists that the West has usually achieved its goals in war because its methodology is so seldom shackled by any consideration other than military necessity. While it graphically describes many military events, his book remains a kind of aerial survey of the landscape of war, one in which Hanson, according to the New York Times' review of the book, "more than makes his case" that a uniquely Western ruthlessness, spawned by uniquely Western cultural values, has led to a world in which Western military forces reign supreme.

In "The Bridge at No Gun Ri," on the other hand, the story takes us down onto the killing fields for days at a time, sharing the wartime experiences of individuals. So we find ourselves cowering with them in a pitch-black ditch to avoid a ferocious rain of "friendly fire," or watching as another young woman, Yang Hae-sook, plucks her own dangling eyeball off the string of her nerves.

"The Bridge at No Gun Ri" is an expanded version of a Pulitzer Prize-winning story about the large-scale massacre in 1950 of unarmed South Korean civilians by U.S. troops, a story broken by a team of Associated Press investigative reporters in 1999. The slaughter was just one part of the hot, sweating military debacle that unfolded during the first few desperate weeks of the Korean War. As their communist North Korean opponents drove them relentlessly backward down the Korean peninsula from Seoul, the inexperienced American troops and their Republic of Korea allies retreated to what they hoped would be a defensible corner of the country called the "Pusan Perimeter." With them and behind them was a displaced and panicky civilian populace, many of whom had been driven from their villages.

As soon as the allies crossed the Naktong River into the Perimeter that August, they turned around and blew up the refugee-choked bridges to prevent the enemy from crossing behind them, in the process killing hundreds of screaming civilians on the spans and stranding the remaining thousands of refugees between the river and the North Korean guns. Then the Americans, under written orders, began systematically shooting any refugees who attempted to cross the water. Although the 7th Cavalry Regiment's slaughter of civilians at No Gun Ri, which is at the heart of the AP journalist's book, occurred a few days earlier and farther back along the line of retreat, the "reasoning" behind it was much the same as that which drove the order to shoot civilians trying to cross the Naktong river. The American high command feared that among the throngs of refugees were North Korean infiltrators trying to get behind American lines where, it was thought, they would abandon their civilian disguises and fall upon the allies from the rear.

That was the story, anyway. However, while enemy infiltration is certainly a realistic concern once warfare has degenerated into guerilla operations, there was little reason for the North Koreans to resort to such subterfuges at that point in the conflict. The allies were so thin on the ground and so lacking in discipline and experience that conventional North Korean forces easily outmaneuvered them. Some parts of the American front were literally miles apart, permitting the North Koreans to make flanking incursions between two parts of the army. The demolition of the Naktong River bridges was arguably a military necessity, but the North Korean troops were still miles away when the bridges were dynamited. There's little doubt that the more immediate concern at that moment was to stop the refugees from crossing into the Perimeter.

Hanson would be likely to see the Korean refugees' ordeal -- being shot at and blown up by the very forces that were supposedly sent to save them -- as an example of "cultural crystallization," where "insidious" and "murky" elements of Western culture become "stark and unforgiving in the finality of organized killing." That's a fancy way of saying that the stories Americans were telling themselves, true or untrue, when they came to Korea -- about who they were, why they were in this war-torn Asian nation, and who they were dealing with -- were the driving force and underlying structure of the nationwide massacre in which No Gun Ri was only a bloody blip. The stories, which focused Western cultural values and fears on the refugees, were the justification for the killings.

And a sense of justification for inflicting widespread death seems to be crucial for Western warriors, despite Hanson's claim that the cutthroat qualities of Western warfare are merely pragmatic or "amoral." We in the West have in fact created whole systems of moral justification for our conduct of warfare, which Hanson acknowledges -- and even contributes to -- whether he realizes it or not. First, the war stories he chooses to tell us highlight the qualities of Western culture most Westerners -- or at least conservative Westerners -- would consider positive: the concepts of individual freedom, decisive efficiency, consent of the governed, private property, innovative technology, capitalism, voluntary discipline and the tolerance of dissent and critique. In the end, Hanson makes a seductive case for the idea that because Western warfare has been incredibly murderous, it has also been relatively speedy and decisive, and has served arguably "good" long-term causes -- the important one by his lights, of course, being the advancement of the more treasured elements of Western civilization.

While Hanson honestly admits that, as in the case of the British invasion of Zululand, there is often little or no moral justification for the initiation of the conflicts he dissects, the stories he tells nonetheless almost uniformly congratulate and justify the "amorally" bloody Western way of war. It is only when warriors abandon their good -- or at least extremely practical -- Western principles, Hanson says, that they begin to lose.

That seems to have been the case with the early losses in Korea, a ground war that American military doctrine had only the year before dismissed as neither necessary or winnable. Most of the Army units sent so hastily into battle were green and untrained (so much for Western "discipline"), their equipment was old and inadequate ("superior technology" it wasn't), their numbers were underwhelming (hardly an application of "decisive" strength) and their leadership was either incompetent or disastrously overconfident (there wasn't a "self-critiquer" in the lot). Even the pervasive racism that underpinned such events as the No Gun Ri disaster was a repudiation of the basic respect for individuals and their personal freedoms that Hanson believes is the foundation of Western military strength.

Racism, per se, isn't one of forms of "cultural crystallization" that Hanson itemizes as having an impact on military operations, Western or otherwise, but his survey of nine "landmark" battles shows again and again how it leads to arrogance, a lack of self-examination and, inevitably, an underestimation of the enemy. Cortis's underestimation of the Aztecs at Tenochtitlan and Chelmsford's inattentive attitude toward the Zulu at Isandhlwana are two of the most obvious examples. In Korea, the Americans referred to the Koreans (unimaginatively, given that the same characterizations had been trotted out a decade earlier to describe the Japanese) as "trained monkeys" and "the most barbarian of peoples." The intelligence chief of the 8th Army called them "half-men with blank faces," and most of the lower ranks routinely referred to them by the all-purpose epithet for Asians which apparently arose among U.S. troops in the Philippines during the American takeover -- er, "reorganization" -- in 1905: "gooks."

If any of these Americans had felt the need to examine their assumptions, the earlier history of the 7th Cavalry Regiment would have proven instructive. The regiment's signature tune, "Garry Owen" which gave them their nickname of "The Garryowens," had been adopted by the regiment's early commander, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer. Custer first had it played to accompany an attack on a Cheyenne encampment on the Washita River in Oklahoma in 1868. But in the 1950s the regiment showed little interest in a realistic assessment of Custer. Instead, as part of their orientation to the 7th Cav, recruits sent to Occupied Japan for their largely ceremonial "praetorian guard" duty were shown the Errol Flynn movie "They Died With Their Boots On," a patriotic version of the events at Little Big Horn, where in reality Custer's military arrogance and his racist assumptions about his Native American enemies led to his destruction.

The film depicts Custer as a tragic hero and celebrates his success in ridding the American West of "hostiles." The idea behind the stirring, uncomplicated propaganda dished out to the newcomers, said Sergeant "Snuffy" Gray, was to "get them to love the regiment," and to be unreservedly proud of their past. It seems to have made the desired impression on Norm Tinkler, who was a 19-year-old machine gunner at No Gun Ri. "We just annihilated them," he said of the Korean civilians -- mostly women, children and older men -- killed in the incident. "It was about like an Indian raid, back in the old days."

Pumped full with martial pride as they were -- even though they were largely untrained and completely inexperienced in combat -- when the Garryowens were suddenly sent to Korea in July 1950, they were confident that they would be returning to their comfortable quarters in Tokyo in a matter of weeks. They partook of a "military superiority complex" that had come down from the headquarters of the "acting emperor" of Japan and Supremo of the Far East Command, General Douglas MacArthur. As soon as the North Koreans saw them coming, they told themselves, there would be a rout.

But even as the 7th Cav was arriving in Pohang on July 22, other teenaged Americans from the 35th Infantry Regiment were drowning in a panicky scramble across a rain-swollen stream as they tried to get away from a North Korean attack. Such terrified retreats of Americans from positions where they were outgunned and about to be overwhelmed in the early days of the Korean conflict were so frequent they prompted a new coinage, "bugging out," and the troops often left a shameful trail of dropped weapons, equipment, food, helmets, cartridge belts and even combat boots along the line of flight.

The Garryowens' first night in the combat zone wasn't much more commendable. Cooked by the tropical heat, eaten by rice-paddy mosquitoes, revolted by the smell of human excrement used in the fields and primed with lurid tales of sneak attacks, infiltration and atrocities, the Garryowens dug in a few miles behind the front, which was slowly being withdrawn from the environs of the town of Yongdong, captured that day by the North Koreans. As soon as darkness fell, the nervous soldiers began shooting at anything that moved or made a sound. One second lieutenant was killed by his own troops when he lit a cigarette in view of the raw, jittery kids in their foxholes.

Meanwhile, several miles away on the Yongdong road, Park Hee-Sook, Yang Hae-sook and their families were being rousted out of their villages by other Americans attempting to clear the area between the armies, to create what was to become known as a "free fire zone" in another conflict a generation later.

In the wee hours of the next night, the Garryowens were ordered to pull back toward No Gun Ri in a routine maneuver designed to straighten and strengthen their front line. But when the order reached the anxious company commanders, they thought it meant there had been a North Korean breakthrough and that they were in danger of being overrun. Soon a mad, blundering fire fight broke out in the inky blackness between two different units of the American forces who each thought they had encountered the enemy. A story circulated amid the melie that the refugees and their carts and oxen, which the Americans could hear moving behind them as they withdrew, were either actual enemy troops and tanks or a shield of civilians being deliberately pushed forward in front of advancing North Korean troops.

As morning dawned, the crowd of refugees, under a small American escort, was approaching the "exhausted, unnerved and hungry" Garryowens, who had settled in on the heights at either side of the road that paralleled the rail line coming east from Yongdong. Orders had been sent down two days earlier from Division headquarters. "No refugees to cross the front line," the order read. "Fire everyone trying to cross lines. Use discretion in case of women and children."

Most commanders, however, had heard the same stories Gil Huff, the regiment's executive officer did, over and over again. Refugee women, it was rumored, were being caught with weapons and radios hidden in their supposedly pregnant bellies or under the babies on their backs. "I never saw one," Huff said later. "But it makes a good story, a colorful story." In any case, it was one that was certainly believed by the skittish recruits at No Gun Ri.

The Air Force was not invited to make exceptions for women and children as they saw fit. Their pilots had been ordered to fire on all refugee parties approaching American positions, whenever they were seen and whoever they might be. Turner Rogers, operations chief of the 5th Air Force, had his doubts about the policy. His fliers were complying, he wrote in a July 25 letter to his superior, but the carnage was likely to attract unwanted press attention sooner or later, and that could prove "embarrassing." Furthermore, Rogers was annoyed that the Army was not taking care of the problem of refugees themselves, on the ground. He couldn't understand why they weren't "screening such personnel or shooting them as they come through if they desire such action." Besides, Rogers, said, there were many targets of much greater military utility that the Air Force should be addressing instead.

But the policy was still in place on July 26, 1950, when, according to witnesses, U.S. planes either strafed or dive-bombed the refugee column as it rested near the railroad bridge at No Gun Ri. On the higher ground above the crossing, the stressed-out Garryowens apparently took the Air Force attack, and the refugees' mass flight toward the relative shelter of the high tunnels of the bridge, as the signal to fire -- and keep firing -- on the bleeding, hysterical, screaming crowd.

The Americans escorting the refugees were caught in the crossfire, too, and several of them took shelter with some of the terrified refugees in a small culvert not far from the railway. Somebody starting firing in at them. "It was like a hornet's nest in there," said Pfc. Delos Flint. "One of my buddies got hit. Shot off part of his privates. Hurt him bad. We was in there hours."

The new 8th Army refugee plan had been radioed down to the divisions just that morning, essentially contradicting Flint's mission to clear the area and herd the civilians south: "No repeat no refugees will be permitted to cross battle lines at any time." Still, no evidence has been uncovered that points to anyone in the chain of command giving a direct order to fire on the refugees at No Gun Ri. "The word" just "came down the line," and most of the troops assumed that someone, somewhere, must have gotten an order, since everyone was shooting.

It continued, on and off, for a couple of days. Many, but not all, of the Garryowens understood that they were to continue to "hold" the railroad bridge against the civilians by firing into the people huddled below it whenever they spotted movement.

Some of the Americans thought they were being sporadically fired on from underneath the trestle, but the bullets they thought were aimed at them were probably from the guns their buddies were firing into the other end of the 40-foot-tall concrete arches. Norm Tinkler, the teenaged machine gunner, detailed how he was able to shoot the refugees under the spans. "I ricocheted them in there," he said. "I knew how to shoot. Oh, I could see about that much of the wall that was going into the tunnel, and I put it on that." In any case, the regimental diary compiled after they withdrew on July 29 reported no guns captured or North Korean soldiers killed at the bridge.

There's a reason that FUBAR ("Fucked Up Beyond All Recognition") began its life as a military acronym. In desperate, fearful situations where confused people -- people toting guns, grenade launchers and mortar tubes -- think their lives are at stake, deaths will occur, usually on a wholesale scale, whether or not they are "supposed" to according to the official rules of engagement.

In any case, as Hanson says from his chilly "Carnage and Culture" viewpoint, the dividing line between "honorable" and "criminal" killing in warfare is essentially arbitrary. "Due to our Hellenic traditions," he writes, "we in the West call the few casualties we suffer from terrorism and surprise 'cowardly,' the frightful losses we inflict through open and direct assault 'fair.'" Incinerating thousands of Japanese civilians in the kind of bombing raids recently cheered in the film "Pearl Harbor" is usually seen by Westerners as not nearly as ghastly as the summary beheading of the parachuting B-29 fliers in China when they were captured.

The whole concept of "civilized warfare" -- the idea that certain forms or targets of military violence are unthinkable or immoral -- is a convenient mythology that not incidentally permits Western military strengths full rein. It also offers opportunities for us to tell good stories about the "devious," "shameful" and "sickening" atrocities perpetrated by our enemies -- and only by our enemies. As with other mythologies, the "civilized warfare" fantasy and the idea that Americans have, can and should practice it, is an article of almost religious faith.

That accounts in large part for the furious reaction of military partisans when incidents like No Gun Ri garner publicity in the West. And then we must assure ourselves, with another good story, that even if such things did happen (My Lai, anyone?), they were "isolated incidents" and that most "civilized" Westerners don't kill unarmed women and children. We can't ever admit the expedient nature of our cherished folklore. Hanson's view of warfare, one that concentrates exclusively on the clash between armed belligerents, only tells part of the story. We believe in the concept of civilized warfare, and that allows us to pretend that civilians are not or should not be targets. Yet they always suffer and die in wars, and in some cases, as in bombing raids on cities, they are also unquestionably targets.

At the same time, Hanson claims that many of the war stories we're telling ourselves these days limit our ability to apply our particularly Western warmongering gifts of annihilating firepower and utter ruthlessness. He takes the story of the 1968 Tet Offensive in Vietnam as a case in point. North Vietnam's multi-focal surprise effort, hitting simultaneously at locations all over South Vietnam during a holiday cease-fire (underhanded! dishonorable! Hanson notes), was actually a military failure for the attackers. Few South Vietnamese joined in the staged "uprising," and tens of thousands of Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army lives were lost. Their death toll was especially heavy in their expulsion from the "Citadel" at Hui and during the siege at Khe Sanh, and there were relatively few losses on the American side.

But while the military effect of Tet was minimal, culturally it was devastating. The way the tale was told by Western journalists, from the inevitably grim street-level view of the common soldier (and with few countervailing facts concerning the larger military situation), shocked and demoralized Americans and South Vietnamese alike. The effect of the offensive was particularly devastating coming as it did after Gen. Westmoreland's confident statements the preceding November that the Vietnam war was "winding down" and that he could see "light at the end of the tunnel."

The demolition of Westmoreland's pleasant fiction of imminent victory accelerated what Hanson otherwise sees as the Western virtues of dissent and self-critique about the conduct of warfare. In some of his landmark battles, the participants' internecine fighting over intent and methodology actually improved their strategy and tactics, and the pooling of brainpower helped them avoid pitfalls. But in retrospect, the deep divisions between the military and its civilian controllers over matters of mission and scope in Vietnam created a military no man's land where there was no possibility of victory. The stories our journalists were telling us -- "We're doing this for nothing" or "We're making no strategic progress" or "We're perpetrating more horrors than we're stopping" -- Hanson maintains, essentially prevented the military from acting in accordance with other, more crucial Western characteristics like our preference for direct, pitiless and decisive battle, and our tendency to systematically continue any given slaughter until the enemy's ability to return to the field is completely obliterated.

Our leaders' acceptance of convincing scenarios about the potential entry of China or the Soviet Union into the Vietnam conflict also warped our military decisions and responses. We hesitated to mine North Vietnamese harbors or to effectively bomb military and industrial facilities or to stringently and directly interdict supply lines in Cambodia and Laos.

Worst of all, according to Hanson, we didn't let ourselves even dream of invading North Vietnam itself with the full, efficient weight of our military superiority. A completely serious Western-style military assault on the North would have been horrifically costly on both sides, of course, but the overall human losses might have been significantly less in the long run (especially if we add the deaths that occurred after the fall of South Vietnam). But we didn't have the will to win that way, and we didn't have the grace to quit.

The stories told in both "Carnage and Culture" and "The Bridge at No Gun Ri" foster two entirely opposite dangers. Hanson pretends that he has laid aside questions of morality, but his thesis actually presents a moral justification for gigantic, no-holds-barred, scorched-earth warfare by arguing that this strategy makes the most productive use of resources, is most likely to achieve definitive victory and is soonest over. Shooting or bombing refugees who might conceivably have posed even the slightest danger to the allied troops is therefore perfectly in consonance with his principles of "amoral" efficiency. "The Bridge at No Gun Ri," on the other hand, demonstrates what Hanson's businesslike sort of warfare involves at the human level, and is likely to make Westerners protest the use of such brutality in the future.

In the Western way of war, there is a constant tension between utility and justification, which has only grown greater as our culture has developed. The Western principles of individual freedom and the consent of the governed weigh heavily on the kinds of stories we are able to tell ourselves about why and how we will make war. A free press protected by the ideals of democratic government and a mass media created by capitalism and innovative technology can now widely disseminate war stories, like that of No Gun Ri, that bring us face-to-face with the realities of combat and utterly destroy our ability to believe in the gallant mythology of "civilized warfare." Thus Western culture might now have "crystallized" to the point that our growing interest in honesty and truth about war could hamper our future ability to apply the ugly but pragmatic principles of our past triumphs.

Hanson is right that Western civilization, such as it is, was built and maintained on carnage of the most obscene and terrifying kinds, up to and including firebombings of cities and distraught kids killing refugees -- and their own buddies -- in battlefield backwaters. The question now is whether Westerners can view blood-chilling true stories of retail warfare like "The Bridge at No Gun Ri" with a clear eye and still recognize the necessity, when and if the time comes, to use our superb abilities -- and our will -- to kick ass and take names.

Shares