Among low-budget backpackers in Asia, there is no more favored topic of conversation than the pretentiousness, vulgarity and cultural insensitivity of other low-budget backpackers in Asia. It's a contempt born of travelers' guilt at their role in spreading the very Western culture they're all fleeing and their embarrassment at how absurd the earnest quest for Third World experience looks when pursed en masse.

Such ambivalence is the dominant theme of the subculture's growing canon of books, all of which feature caustic appraisals of the hordes of dreadlocked, baggy-trousered, ganja-scented drifters who crowd places like Thailand's Kho San Road, Goa's Anjuna beach and Laos' Vang Vieng, where they sit in cafes devouring banana pancakes, chai and the novels that mock them.

Except for "The Beach," Alex Garland's nightmare of neo-hippie atavism, backpacker fiction has never really caught on among Americans, in part because a year spent traveling through the Third World isn't a rite of passage here in the way it is in Europe, Israel and Australia. On the backpacker circuit, though, the volumes are ubiquitous. Books like William Sutcliffe's neurotic India comedy "Are You Experienced?" and Simon Lewis' slick 1999 novel "Go" can be found in bookshops from Katmandu to Koh Phangan -- any Asian spot frequented by white people.

Until recently, though, these books have been strictly a boy thing. There are thousands of young women traveling solo or in pairs through Asia, navigating the ordinary perils of life on the road -- loneliness, aimlessness, amoebic dysentery -- as well as the clutches of predatory men, but their stories hadn't been told.

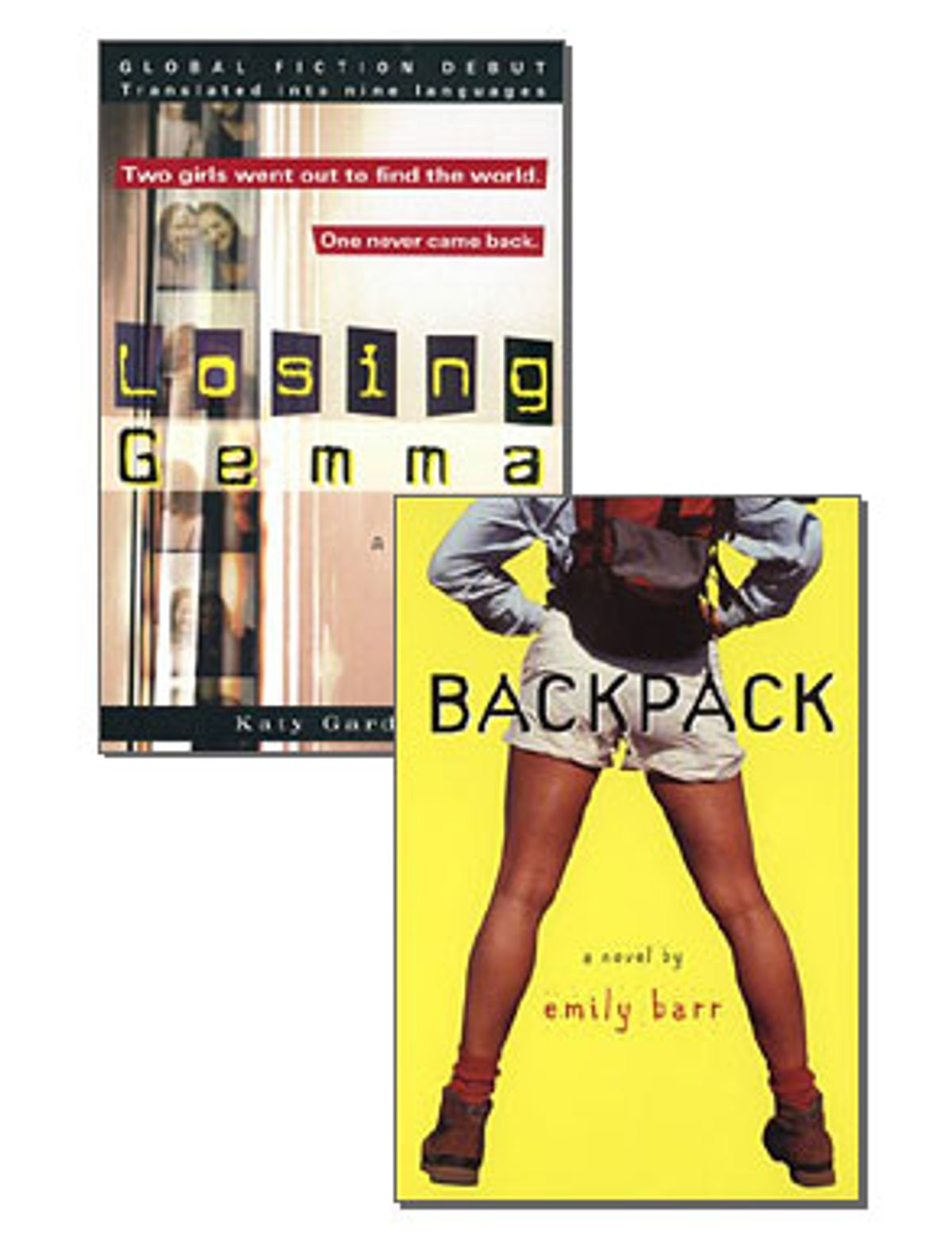

It was only a matter of time. This year, there have been two extremely entertaining English novels about young women roaming the world, both of which satirize the backpacker scene while offering fresh perspectives on the dilemma of adventure-seekers in a world where most of the thrills seem secondhand. "Losing Gemma," by Katy Gardner, and "Backpack," by Emily Barr (already a bestseller in Britain), reinvent oft-told tales of frustrated vagabonds by making them stories about the endless female quest for self-improvement.

The two books are strangely similar. Both feature deliberately obnoxious, attractive Englishwomen in their 20s whose delusions of worldliness evanesce once they arrive in Asia. Both books revolve, in part, around the violent deaths of other female backpackers, deaths that clearly underline the anxieties likely to plague even brave women. In each, a beach holiday taken on touristy Thai islands signifies a fall away from intrepid ideals and into holidaymaker banality. And of course, both women end up humbled but wiser, liberated from oppressive vanity.

(Spoiler alert: Stop reading here if you don't want to learn the details of the plots.) The biggest difference between the books lies in the execution of their murder plots. In "Losing Gemma," the death of the title character is at the center of the book, while in "Backpack" a serial killer stalking blond English travelers across Asia is an unfortunate, hollow distraction from what is otherwise an absorbing, darkly funny tale of self-discovery in expertly rendered exotic locales.

The animating mystery in "Losing Gemma" is a gripping, psychologically resonant one. Beautiful Esther regards her lifelong best friend Gemma as a dumpy sidekick and treats her with affectionate condescension. When they go to India together, Esther feels entitled to make all their plans and drags Gemma to an obscure village they'd been warned against. On the way, they meet Coral, a nomadic, flaky waif who drives Esther crazy by embodying much of what she aspires to. As Gemma allies herself with Coral, and Esther finds herself shut out, Gardner wonderfully illuminates the currents of envy and power that disfigure friendships. By the time Esther begins to suspect Coral's involvement in some kind of cult, Gemma wants nothing to do with her old friend. When Gemma eventually disappears and is declared dead, Esther is destroyed by guilt.

Conversely, in "Backpack," the murders that terrify Tansy could have been easily excised from the book without changing its structure much at all. The meat of the story involves her transformation from supercilious, street-cred-seeking urbanite to genuine traveler. She learns to stop sneering at those around her and to stop worrying about being a clichi, and she leaves her loutish London boyfriend for a sensitive, gallant wanderer. The murders (culminating in a pulpy but predictable revelation) cheapen what would otherwise be a fluffy but astute backpacking bildungsroman.

The most striking convergences between the two books are not, however, those of plot but those of character. That isn't because the authors lack originality -- rather, the parallels arise because both do an excellent job of capturing a very definite type, one that's rarely been explored in fiction before. Tansy, the cokehead jilted journalist of "Backpack," and Esther, the self-absorbed would-be bohemian of "Losing Gemma," are as much in pursuit of romantic images of themselves as of actual romance. They're in thrall to their own self-conceptions.

"Above all, I'll be skinny and brown," thinks Tansy. "I'll wear little sarongs and tiny vests, and I'll stand around looking lovely and thinking deep thoughts." Similarly, upon seeing some grungily glam fellow backpackers, Esther, the narrator of "Losing Gemma," thinks, "I wanted to be like that, too, with dusty feet and slim brown wrists encased in lines of sparkly bazaar bangles."

These women don't fantasize about having experiences so much as about having had them. "Perhaps I will have tales of soul-searching: 'I spent six months on a beach in Thailand staring into the depths of my self -- it wasn't a pretty sight'; 'I sat in a slum in Calcutta with rats running around my feet and cockroaches in my hair, and I suddenly realised what true happiness was,'" Tansy thinks. "Yes, the year itself will be a small price to pay."

Of course, such persona-cultivation isn't unique to women -- the hero of "Are You Experienced?" also sees travel as something to get over with so he can brag about it afterward. Yet these books suggest that the obsession with creating an interesting lifestyle instead of an interesting life falls particularly hard on women, who are accustomed to imagining themselves through the eyes of others or the lens of a camera. Backpacker lit in general deals with the melancholy farce of kids trying and failing to live out previous generations' uncommercialized dreams -- as well as the moments of grace when immediate, transcendent experience wipes everything else away. "Losing Gemma" and "Backpack" add to this the self-consciousness of women who see travel as a route out of their perceived mediocrity, but instead find that it makes those perceptions irrelevant.

Eventually, both Tansy and Esther find redemption through self-acceptance in faraway places, as circumstances force them to give up the quest for idealized selves. The endings of both books are a little pat, but the journeys are compelling and even surprising, no matter that the ground has been covered before.

Shares