Even before the Supreme Court decision awarded the presidency to the Republicans in December 2000, the Bush team began behaving as if it had won. The election took place exactly 10 years after the buildup of American troops in Saudi Arabia for the Gulf War, and to mark both that occasion and the impending Bush restoration, former president George H.W. Bush and former secretary of state James Baker had proposed a hunting trip in Spain and England. The original guest list included the usual suspects from the Gulf War -- the senior Bush; James Baker; Dick Cheney; General Norman Schwarzkopf, the commander of U.S. forces during the war; former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft; and, of course, Saudi Arabia's Prince Bandar, whose enormous estate in Wychwood, England, had been an ancient royal hunting ground used by Norman and Plantagenet kings.

The relationship between Baker and the elder Bush had been frayed as a result of the failed reelection campaign of 1992, but the two longtime friends had patched things up as the presidency of George W. Bush became increasingly probable. When he arrived in Austin, Texas, on Election Day, Baker went to Dick and Lynne Cheney's hotel suite to listen to the results. However, by the next morning, Wednesday, Nov. 8, Al Gore was contesting the Florida vote, so Baker was enlisted to lead the legal battle to win the presidency for Bush. As a result, both he and Cheney skipped the European hunting trip.

But the lavish gathering went on as planned. On Thursday, Nov. 9, a private chartered plane from Evansville, Ind., picked up former president Bush in Washington en route to Madrid, where the hunting trip was to begin. Already on board was a contingent from Indiana. One member was Bobby Knight, the highly successful but extraordinarily temperamental basketball coach who had just been fired from Indiana University. Other hunters on the trip were powerful coal industry executives from the Midwest -- Irl Engelhardt, the chairman and CEO of St. Louis's Peabody Energy, the world's largest coal company; and Steven Chancellor, Daniel Hermann and Eugene Aimone, three top executives of Black Beauty Coal, a Peabody subsidiary headquartered in Evansville.

During the campaign, Bush had proposed caps on the carbon dioxide emissions that scientists believe cause global warming, a regulatory measure that coal executives had not welcomed. But among them, the coal executives had contributed more than $700,000 to Bush and the Republicans. They still had high hopes of participating in energy policy in a Bush administration and loosening the regulatory reins around the industry. Even though the recount battle was just getting under way in Florida, the Bush family was back in action, mixing private pleasure and public policy.

Once in Spain, Bush, Knight and the executives were joined by Norman Schwarzkopf and proceeded to a private estate in Pinos Altos, about 60 kilometers from Madrid, to shoot red-legged partridges, the fastest game birds in the world. Bush impressed the hunting party as a fine wing shot and a gentleman -- the 76-year-old former president was not above offering to clean mud off the boots of his fellow hunters. Throughout the trip, Bush kept in touch with the election developments via e-mail. By Saturday, Nov. 11, a machine recount had shrunk his son's lead in Florida to a minuscule 327 votes. "I kind of wish I was in the U.S. so I could help prevent the Democrats from working their mischief," he told another hunter in his party.

On Tuesday, November 14, Bush and Schwarzkopf arrived in England, where Brent Scowcroft joined them and they continued their game hunting on Bandar's estate. They kept a close eye on the zigs and zags of the recount battle. As a power play to demonstrate his confidence to the media, the Democratic Party, and the American populace, George W. Bush announced the members of his White House transition team even before the Florida vote-count battle was over.

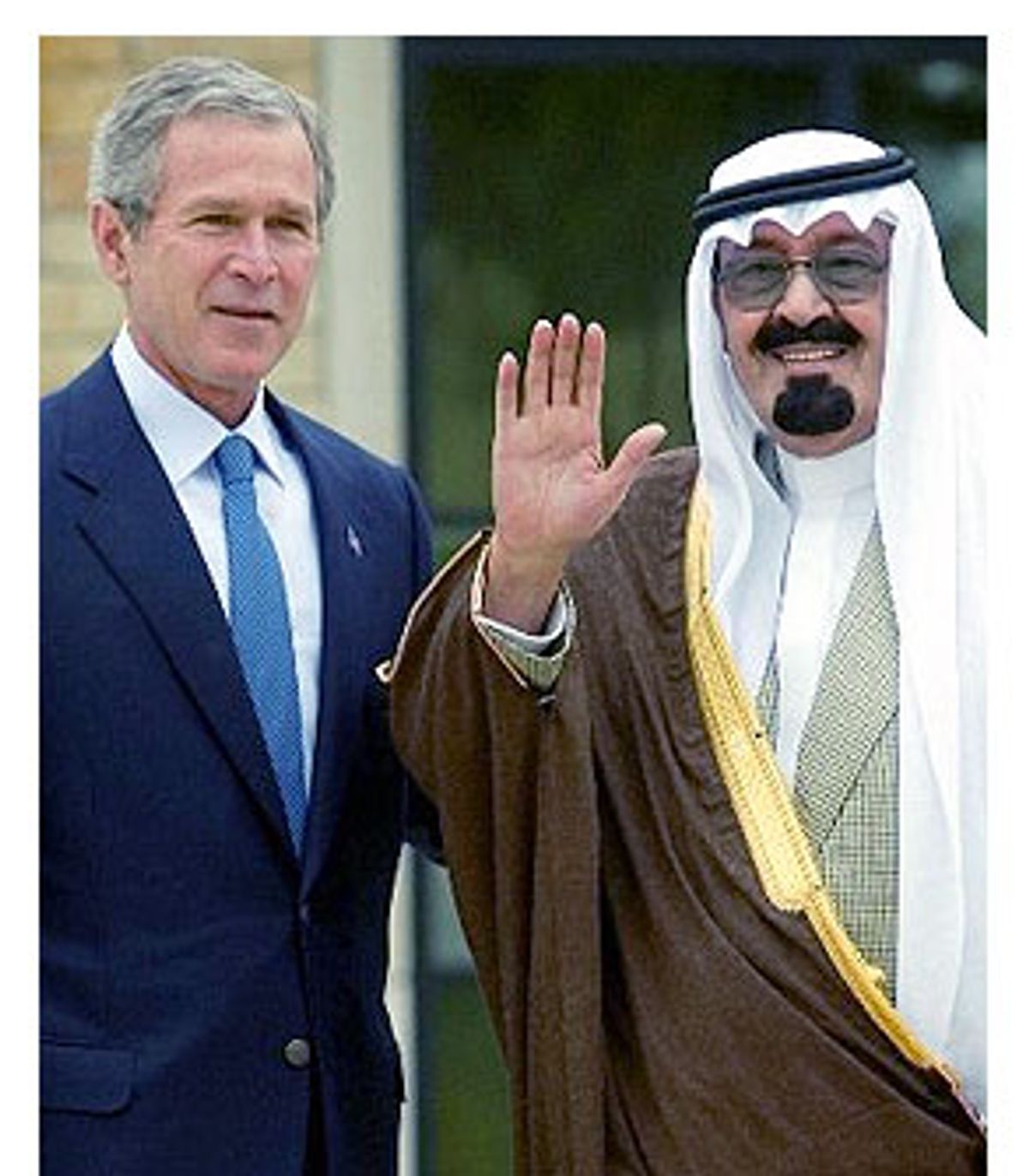

Bandar eagerly anticipated seeing the Bush family back in Washington. Dick Cheney, Colin Powell, and Donald Rumsfeld were men Bandar already knew quite well. Others who would have access to a new President Bush -- his father, James Baker, Brent Scowcroft -- were also old friends.

Moreover, a Bush restoration would also strengthen Bandar's position in Saudi Arabia. During the 12 years of the Reagan-Bush era, Bandar had enjoyed unique powers -- partly because of his close relationship to Bush, partly because he always had King Fahd's ear. But during the Clinton era, Bandar had lost clout. Never an insider in the Clinton White House, he had disliked what he called the "weak-dicked" foreign policy team of the Clinton administration. Bandar had also lost ground in Riyadh because Crown Prince Abdullah, who had effectively replaced the ailing King Fahd, had never been particularly fond of Bandar. But now, on his estate in England, Bandar was once again wired into the real powers that be, and assuming that Bush won, he would be back in a position that no other prominent foreign official could come close to.

The anticipatory mood of the Bush-Bandar hunting trip contrasted sharply with what was going on in the White House, where, during the last days of the Clinton administration, the central figures in the battle against terrorism were frustrated beyond all measure. In the wake of the bombing of the USS Cole just a few weeks earlier, counterterrorism czar Richard Clarke -- officially, head of the Counterterrorism Security Group of the National Security Council -- felt acutely that the threat of Islamist terror was greater than ever. But since the Clinton administration was leaving office, it was unclear what he would be able to do about it.

A civil servant who had ascended to the highest levels of policy making, Clarke was a true Washington rarity. As characterized in Steven Simon and Dan Benjamin's "The Age of Sacred Terror," he broke all the rules. He refused to attend regular National Security Council staff meetings, sent insulting emails to his colleagues, and regularly worked outside normal bureaucratic channels. Beholden to neither Republicans nor Democrats, the crew-cut, white-haired Clarke was one of two senior directors from the administration of the elder George Bush who were kept on by Bill Clinton, and abrasive as he was, he had continued to rise because of his genius for knowing when and how to push the levers of power.

Obsessed with the fear that Osama bin Laden's next strike would take place on American soil, after the USS Cole bombing Clarke had prepared a proposal for a massive attack on bin Laden and al-Qaida in Afghanistan. But Clarke's plan faced one major obstacle. On Tuesday, Dec. 12, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled by a vote of 5 to 4 that the recount of the disputed votes in Florida could not continue. In effect, it had awarded the presidency of the United States to George W. Bush.

Eight days later, on Dec. 20, Clarke presented his plan to his boss, National Security Adviser Sandy Berger, and other principals on the National Security Council. But with only a month left in the Clinton administration, Berger felt it would be ill-advised to initiate military action just as the reins of power were being handed over to Bush.

At the same time, Berger was obligated to make clear to the Bush team that bin Laden and al-Qaida posed a national security threat that required urgent and aggressive action. As a result, in the early days of January 2001, Berger scheduled no fewer than 10 briefings by his staff for his successor, Condoleezza Rice, and her deputy, Stephen J. Hadley. Berger decided that it was not necessary for him to go to most of the briefings, but he made a point of attending one he felt was absolutely crucial. "I'm coming to this briefing to underscore how important I think this subject is," he told Rice. At that meeting Clarke presented the incoming Bush team with an aggressive plan to attack al-Qaida.

The meeting began at 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday, Jan. 3, 2001, in Room 302 of the Old Executive Office Building, a room full of maps and charts that had become home base for Clarke and his chief of staff, Roger Cressey. With Rice present, Clarke launched into a PowerPoint presentation on his offensive against al-Qaida. Bush administration officials have denied being given a formal plan to take action against al-Qaida. But the heading on slide 14 belies that denial. It read, "Response to al-Qaida: Roll back." Specifically, that meant attacking al-Qaida's cells, freezing its assets, stopping the flow of money from Wahhabi charities and breaking up al-Qaida's financial network. It meant giving financial aid to countries fighting al-Qaida such as Uzbekistan, Yemen and the Philippines. It called for air strikes in Afghanistan and Special Forces operations. The Taliban had been in power in Afghanistan since 1996, and because they were providing a haven for and being supported by Osama bin Laden, Clarke proposed massive aid to the Northern Alliance, the last resistance forces against them.

Most significantly of all, Clarke called for covert operations "to eliminate the sanctuary" in Afghanistan where the Taliban was protecting bin Laden and his terrorist training camps. The idea was to force terrorist recruits to fight and die for the Taliban in Afghanistan, rather than to allow them to initiate terrorist acts all over the world. The plan was budgeted at several hundred million dollars, and Time reported, according to one senior Bush official, it amounted to "everything we've done since 9/11."

After the session, Berger underscored the challenge the next administration faced. "I believe that the Bush administration will spend more time on terrorism generally, and on al-Qaida specifically, than any other subject," he told Rice.

It seems fair to say that until this point Condoleezza Rice had not taken Islamist terrorism seriously as a threat. Less than a year earlier, in a lengthy article in Foreign Affairs, Rice had voiced her contempt for the Clinton administration's foreign policies, and expressed her views on America's strategic foreign policy concerns. Her brief references to terrorism in the article suggest she saw it as a threat only in terms of the state-sponsored terrorism of Iran, Iraq, Libya and other countries that predated the transnational jihad of bin Laden and al-Qaida. And in her speech before the Republican National Convention, Rice had not mentioned terrorism at all. Rather she had suggested that America's most difficult foreign policy challenges would come from China.

After the briefing, Rice, who was about to become Clarke's boss, admitted to him that the dangers from al-Qaida appeared to be greater than she had realized. Then she asked him, "What are you going to do about it?" According to Clarke, "She wanted an organized strategy review." But she did not give Clarke a specific tasking.

During the changeover from an old administration to a new one, incoming officials frequently fall victim to "death by briefing" by each component of the government. Thus well-intentioned, carefully prepared plans from one administration may be sacrificed in turf wars or be lost in transition as a new administration takes office. Some members of the Bush team saw setting up a new missile defense system as their highest priority. For his part, incoming Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld wanted to overhaul the entire structure of the military. As a result, Bush, Cheney and Rumsfeld all wanted to go after Iraq. Clarke's proposal sat there and sat there and sat there.

Nothing happened.

Shares