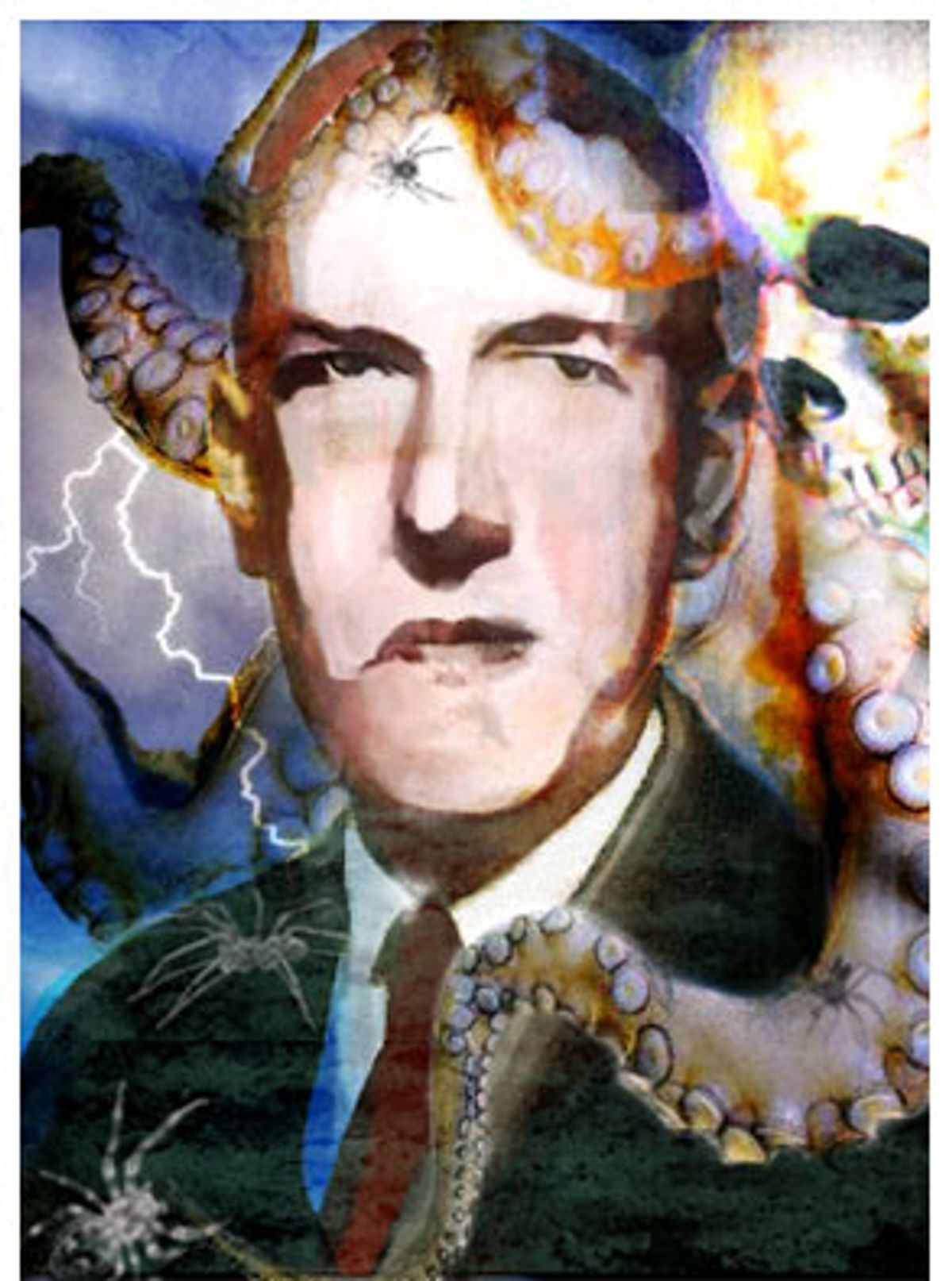

"From the greatest of horrors irony is seldom absent," reads the first line of the H.P. Lovecraft story "The Shunned House," but chances are Lovecraft, who died in 1937, wouldn't have appreciated the irony of his present position as American literature's greatest bad writer. There are two camps on the subject of the haunted bard of Providence, R.I., and his strange tales of cosmic terror. One, led by the late genre skeptic Edmund Wilson, dismisses him as an overwriting "hack" who purveyed "bad taste and bad art." The other, led by Lovecraft scholar and biographer S.T. Joshi, hotly rises to Lovecraft's defense as an artist of "philosophical and literary substance."

The second camp seems to have scored a solid point with the publication of "H.P. Lovecraft: Tales," a new collection from the Library of America, a publisher specializing in "preserving America's best and most significant writing in handsome, enduring volumes featuring authoritative texts." Lovecraft's champions may comfort themselves with the fact that there is, as yet, no Library of America volume devoted to Edmund Wilson's work.

But ambivalence remains, even on the home team. In an interview with Salon, Stephen King characterized his predecessor as best read by teenagers and other people "living in a state of total sexual doubt." One writer I know, a winner of the World Fantasy Award and recipient of a trophy shaped like a bust of Lovecraft, will insist, when asked, that the statuette is of Jacques Cousteau. Perhaps most tellingly, even the celebrity author brought in to write the notes for the Library of America collection, horror novelist Peter Straub ("Ghost Story"), confessed to Publishers Weekly that Lovecraft had "only a minimal influence" on him and that during his 20s, "being very literary and self-conscious about it," he had written Lovecraft off as inferior.

But whether or not Lovecraft was a bad, a great or (more sensibly) a worthwhile writer is in some ways beside the point. For readers of a certain inclination, his tales are fascinating and addictive. He has a sizable following, manifesting itself in everything from countless fan sites to role-playing games to praise from such notable admirers as critic (and Library of America editor in chief) Geoffrey O'Brien, novelist Joyce Carol Oates, and composer-musician Stephin Merritt, of the Magnetic Fields.

Perhaps the most curious thing about Lovecraft is that much of what aficionados love about his work is exactly those things his detractors list as faults. Take, for example, the fact that while Lovecraft is usually described as a forefather of modern horror fiction, his stories are, to put it bluntly, not very scary. Wilson complained, with perfect justification, that Lovecraft ladled on the frightful adjectives and adverbs when describing -- or even just hinting at -- the nightmarish realizations that typically confront his protagonist at a tale's climax. In "The Lurking Fear," the narrator, recounting his sensations as he is about to discover something awful, explains, "I felt the strangling tendrils of a cancerous horror whose roots reached into illimitable pasts and fathomless abysms of the night that broods beyond time."

Lovecraft's narrators routinely rave about the "hideous," "monstrous" and "blasphemous" nature of their revelations. Wilson went on, again quite reasonably, to observe, "Surely one of the primary rules for writing an effective tale of horror is never to use any of these words -- especially if you are going, at the end, to produce an invisible whistling octopus." That octopus crack is a particularly low blow, since the most celebrated of Lovecraft's stories and novels partake of what has been dubbed the Cthulhu Mythos, an alternative mythology involving an enormous and malevolent being whose tentacled head resembles a cephalopod.

In classic form, a Lovecraft tale begins with a narrator explaining that ordinarily he'd never impart the terrifying secrets he is about to relate, but some urgent cause compels him. Initially, apart from the occasional allusion to "unmentionable" horrors, the voice is relatively calm, authoritative and rational. Often the story is presented as a semi-scientific or semi-official report, compiled from multiple partial accounts. The story's hero encounters some mystery -- a strangely blighted plot of farmland, a friend or relative's research into bizarre and secretive religious cults, nasty goings-on among the residents of a small New England town, etc. -- and in the process of investigating it has his entire conception of the universe overthrown.

What Lovecraft's typical protagonist ultimately discovers, underneath the placid surface of conventional reality, is the existence of heretofore unknown "gods" and other less exalted but equally unpleasant beings. Important figures in the mythos include Cthulhu ("The Great Sleeper"), Yog-Sothoth ("The Lurker on the Threshold"), Shub-Niggurath ("The Black Goat of the Woods With a Thousand Young"), Hastur ("The Unspeakable One"), the ever-popular Nyarlathotep ("The Crawling Chaos") and the supreme entity, Azathoth, a "blind, idiot god," who, we are told, resides at the center of the universe where he/it "gnaws shapeless and ravenous amidst the muffled, maddening beat of vile drums and the thin, monotonous whine of accursed flutes."

Lovecraft intended this pantheon as a metaphor for mankind's harsh encounter with the mindless, mechanical universe unveiled by modern science at the turn of the century. Extensively self-educated, he took a keen interest in science (this makes the scientific passages in his stories particularly convincing) and wrote about astronomy, chemistry and other fields for newspapers and journals. "All my tales," he wrote, "are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large."

The great size, tremendous age and general indifference to humanity of Lovecraft's invented gods is meant to be terrifying in the same way that the contemplation of the infinite and empty reaches of space were to a Western culture shaking off the comforts of religion. Lovecraft intended Cthulhu and company to be utterly alien -- hence the unpronounceable name, the writhing tentacles, and the wonderful detail that the architecture of Cthulhu's city, R'lyeh (usually sunk to the bottom of the ocean, but briefly emerging in "The Call of Cthulhu"), is based on a non-Euclidean geometry that is "loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours." Lovecraft's human characters, when afforded a glimpse of such things, tend to "scream and scream and scream," faint or go stark raving mad.

The truth, however, is that hardly any reader finds Cthulhu frightening. In fact, by all indications, the public is very fond of the creature. You can check in regularly at the Cthulhu for President site ("Home Page for Evil"), purchase a cuddly plush Cthulhu or behold the adventures of Hello Cthulhu, a cross between Lovecraft's "gelatinous green immensity" and the adorable, big-eyed Sanrio cartoon character. Sauron never inspired this kind of affection.

Cthulhu isn't scary partly because it's difficult to imagine the unimaginable, and partly because it's hard to convey the terror of limitless nothingness via an entity that, however bizarre, is nevertheless something. Then there's the stylistic problem: The language Lovecraft uses to describe this and other horrors is so overwrought that the words themselves distract you from the subject. "The Lurking Fear," a story about a man who unearths a tribe of cannibalistic "dwarfed, deformed hairy devils or apes" holed up in a decrepit Catskills mansion, culminates in a hysterical, hallucinatory outpouring that makes Edgar Allan Poe sound like Jane Austen:

"Shrieking, slithering, torrential shadows of red viscous madness chasing one another through endless, ensanguined corridors of purple fulgurous sky ... formless phantasms and kaleidoscopic mutations of a ghoulish, remembered scenes; forests of monstrous overnourished oaks with serpent roots twisting and sucking unnamable juices from an earth verminous with millions of cannibal devils; mound-like tentacles groping from underground nuclei of polypous perversion ... insane lightning over malignant ivied walls and daemon arcades choked with fungous vegetation ..."

This is, as Wilson protested, too much, and yet it is just what the Lovecraft fan lives for, and chortles over and quotes with glee to other fans. Without a doubt, a significant part of Lovecraft's appeal for today's readers is camp. And, as Susan Sontag famously pointed out, true camp is a blend of mockery and love.

To be fair, if the sheer verbiage of Lovecraft's stories does occasionally bog things down, most of his tales maintain the suspense necessary to all pulp fiction. (Lovecraft originally published, when his stories were accepted, in the early pulp magazines of the 1920s.) There is a delicious and inimitable inevitability to the progression of these tales, from the sober first line ("From a private hospital for the insane near Providence, Rhode Island, there recently disappeared an exceeding singular person") to the florid, thesaurus-taxing convulsions of the denouement (once these were rendered in italics; that format has not been reproduced in the Library of America edition).

Still, the combination of purple prose and ripping yarns isn't enough to earn Lovecraft's work the immortality it has genuinely attained. There is a ferocious imaginative power driving these tales, and all the more so for being, to cop a favorite Lovecraftian word, unwholesome. In the Freud-crazed '50s and '60s it became fashionable to denounce Lovecraft's fiction as "neurotic," to which the only conceivable reply is: Duh. How could anyone think of presenting such an observation as an insight when neurosis lies palpitating on the surface of the work? These tales are veritable carnivals of anxiety, repression and rage; that's the source of their appeal. They aren't in any sense healthy, but then neither is the poetry of Baudelaire.

The kernel of Lovecraft's neurosis is a hopeless tangle of sex, race and bodily decay, fed by the tragedies and frustrations of his private life. He was the scion of an old New England family (he boasted of coming from "pure" English stock) that plunged from affluence into genteel poverty during his childhood. His parents both suffered from mental illness (his father's was possibly syphilitic in origin) and as a teenager he endured a nervous breakdown that interfered with his schooling and any conventional socialization. He was tall, thin, pale and extremely bookish, the pet and the target of a mother who was both smothering and critical, particularly of his physical appearance. A brief marriage to an older woman eventually fell apart and after a disastrous try at living in New York, he retired to his native and beloved Providence to live with two elderly aunts.

Lovecraft's biography offers some clues as to why his fiction isn't particularly good at inspiring fear but can powerfully convey another emotion: disgust. The revulsion tends to constellate around smaller details, usually associated with biological forces gone wrong. The doings in "The Shunned House" involve ghostly manifestations and a spectacular possession scene, but the sole detail that reliably provokes a shudder is the diseased "white fungeous growths" that sprout in the house's accursed cellar; they rot quickly and, when cut by the narrator's shovel, ooze a "viscous yellow ichor." The "singular person" detained in the insane asylum in "The Case of Charles Dexter Ward" is described as having skin in which "the cellular structure of the tissue seemed exaggeratedly coarse and loosely knit."

In what even Lovecraft considered his most successful story, "The Colour out of Space," the narrator learns what happened to an unfortunate farmer and his family after a mysterious meteorite lands near their well. The crops looked lush but turned out to be bitter and inedible. The vegetation took on a strange, unearthly color similar to that of a disturbing "globule" found inside the meteorite. Then it began to turn gray, dry and crumbly. The farmer's wife went mad and had to be confined to the attic. The livestock was struck with an affliction in which "certain areas or sometimes the whole body would be uncannily shriveled or compressed, and atrocious collapses or disintegrations were common. In the last stages -- and death was always the result -- there would be a greying and turning brittle."

As Joyce Carol Oates has written, "The Colour out of Space" succeeds in creeping us out where much of Lovecraft's fiction fails because it is "subtly modulated" instead of merely sensational. A whisper works much better than a shriek. The story also feels closer to the heart of Lovecraft's own fears than some of its more cosmic brethren. Although the parallel to radiation poisoning seems obvious, "The Colour out of Space" was written in 1927 and really reflects a more deeply rooted dread of contamination, disease and degeneration. These are the predominant motifs in Lovecraft's imaginative life.

The ugliest way this preoccupation appears in Lovecraft's fiction is in his depiction of nearly everyone not of upper-class Anglo-Saxon descent. The Library of America collection includes "The Horror at Red Hook," the tale of a policeman's efforts to get to the bottom of cult activities in a section of Brooklyn (a poor immigrant neighborhood where Lovecraft himself had lived). The investigation leads him from meditations on the "swarthy, sin-pitted faces" of the inhabitants to a plunge into feverish visions of subterranean devil worship. He perceives these visions to be "the root of a contagion destined to sicken and swallow cities, and engulf nations in the foetor of hybrid pestilence. Here cosmic sin had entered, and festered by unhallowed rites had commenced the grinning march of death that was to rot us all to fungous abnormalities too hideous for the grave's holding."

It was race mixing in particular that seemed to most horrify Lovecraft. His fiction is rife with scenarios of evolution working in reverse, human beings mating with fish people and producing revolting "mongrels." He clung to the idea of himself as a holdover from a past era, an 18th century "gentleman." It's the kind of comforting fantasy common in old families who have nothing left to distinguish themselves but their breeding, but it's inexcusable in someone who claimed to place his ultimate faith in science. Like a lot of people who proudly declare themselves to inhabit the territory of pure reason, Lovecraft had difficulty policing the borders.

At root, all of Lovecraft's phobias seemed to come down to an elemental dread of the human body: the tentacles and gaping abysses with their obvious genital associations (hence Stephen King's comment), reproduction's disorderly tendency toward mutation and of course the horror writer's primal muse -- the death and decay that lie in store for every living thing. If not all of us share the specific racial and sexual manifestations of that dread, we all feel some version of it. Lovecraft, in his fiction at least, abandoned himself to it with a kind of warped gallantry.

If Lovecraft, unlike Poe or King, hasn't the psychological acuity to get under our skin and make us feel real fear, he does offer us the spectacle of his own unfettered morbidity. And as part of the irony that Lovecraft detected in all great horrors, that morbidity proved to be spectacularly fecund. The energy of his psychopathology fueled the creation of the vast, visionary Cthulhu Mythos, an invention big enough for other writers and artists to crawl into, inhabit and expand upon. There's exhilaration in witnessing that energy allowed to run loose, without shame, without self-consciousness and without limit. Which is not to say it's healthy, let alone wholesome. No, I wouldn't call it wholesome at all.

Shares