It was a cool, crisp day in the spring of 2004 -- a rarity for Houston -- and George H.W. Bush chatted with a friend in his office suite on Memorial Drive. Tall and trim, his hair graying but by no means white, the former president was a few weeks shy of his eightieth birthday -- it would take place on June 12, to be exact -- and he was racing toward that milestone with the vigor of a man thirty years younger. In addition to golf, tennis, horseshoes, and his beloved Houston Astros, Bush's near-term calendar was filled with dates for fishing for Coho salmon in Newfoundland, crossing the Rockies by train, and trout fishing in the River Test in Hampshire, England. He still prowled the corridors of power from London to Beijing. He still lectured all over the world. And, as if that weren't enough, he was planning to commemorate his eightieth with a star-studded two-day extravaganza, culminating with him skydiving from thirteen thousand feet over his presidential library in College Station, Texas. All the celebratory fervor, however, could not mask one dark cloud on the horizon. The presidency of his son, George W. Bush, was imperiled.

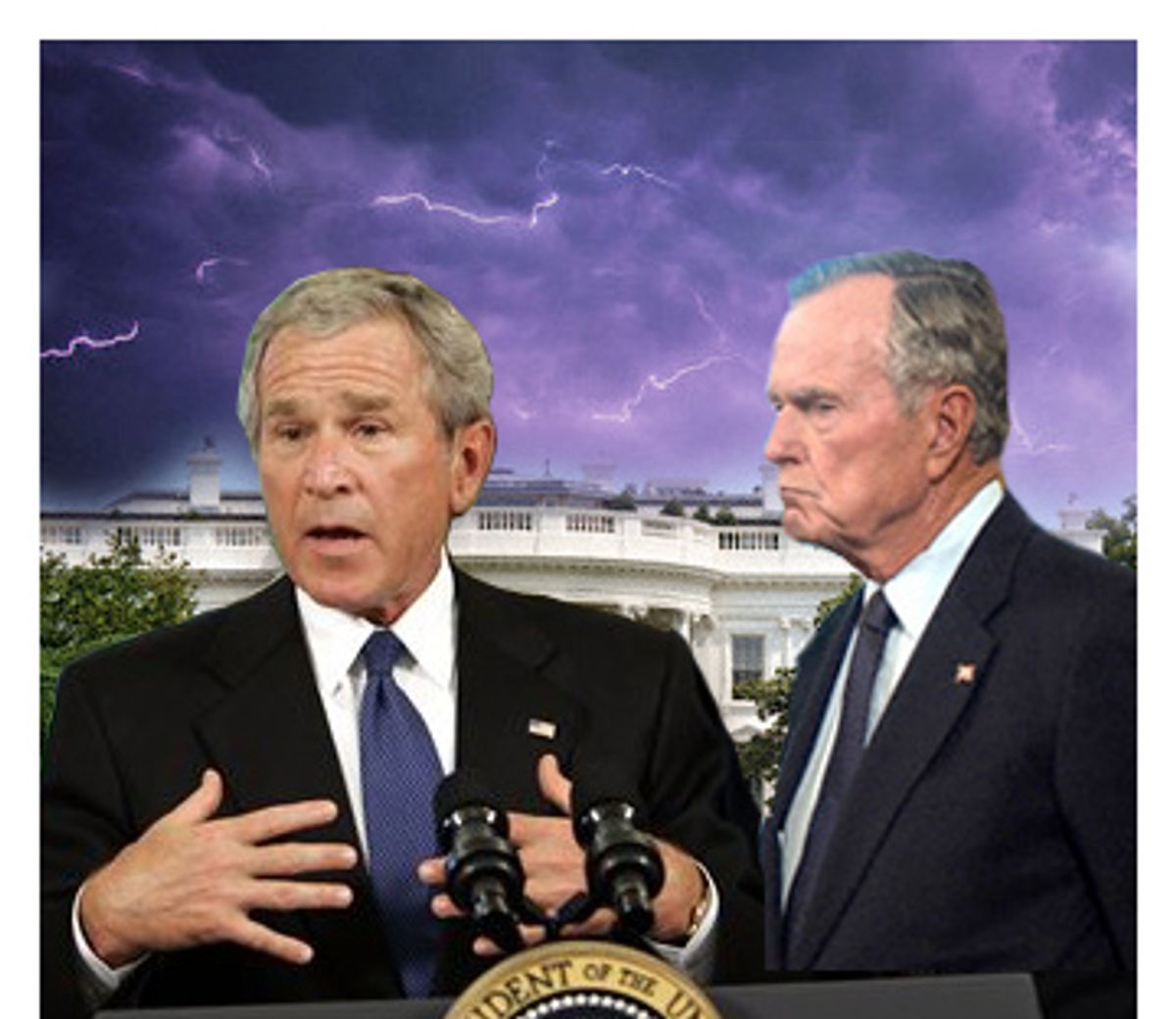

One way of examining the growing crisis could be found in the prism of the elder Bush's relationship with his son, a relationship fraught with ancient conflicts, ideological differences, and their profound failure to communicate with each other. On many levels, the two men were polar opposites with completely different belief systems. An old-line Episcopalian, Bush 41 had forged an alliance with Christian evangelicals during the 1988 presidential campaign because it was vital to winning the White House. But the truth was that real evangelicals had always regarded him with suspicion -- and he had returned the sentiment.

But Bush 43 was different. A genuine born-again Christian himself, he had given hundreds of evangelicals key positions in the White House, the Justice Department, the Pentagon, and various federal agencies. How had it come to pass that after four generations of Bushes at Yale, the family name now meant that progress, science, and evolution were out and stopping embryonic stem cell research was in? Why was his son turning back the hands of time to the days when Creationism held sway?

But this was nothing compared to the Iraq War and the men behind it. George H.W. Bush was a genial man with few bitter enemies, but his son had managed to appoint, as secretary of defense no less, one of the very few who fit the bill -- Donald Rumsfeld. Once Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney took office, the latter supposedly a loyal friend, they had brought in one neoconservative policy maker after another to the Pentagon, the vice president's office, and the National Security Council. In some cases, these were the same men who had battled the elder Bush when he was head of the CIA in 1976. These were the same men who fought him when he decided not to take down Saddam Hussein during the 1991 Gulf War. Their goal in life seemed to be to dismantle his legacy.

Which was exactly what was happening -- with his son playing the starring role. A year earlier, President George W. Bush, clad in fighter-pilot regalia, strode triumphantly across the deck of the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln, a "Mission Accomplished" banner at his back -- the Iraq War presumably won. But the giddy triumphalism of Operation Shock and Awe had quickly faded. America had failed to form a stable Iraqi government. With Baghdad out of control, sectarian violence was on the rise. U.S. soldiers were becoming occupiers rather than liberators. Coalition forces were torturing prisoners. As for Saddam's vast stash of weapons of mass destruction -- the stated reason for the invasion -- none had been found.

Bush 41 had always told his son that it was fine to take different political positions than he had held. If you have to run away from me, he said, I'll understand. Few things upset him. But there were limits. He was especially proud of his accomplishments during the 1991 Gulf War, none more so than his decision, after defeating Saddam in Kuwait, to refrain from marching on Baghdad to overthrow the brutal Iraqi dictator. Afterward, he wrote about it with coauthor Brent Scowcroft, his national security adviser, in "A World Transformed," asserting that taking Baghdad would have incurred "incalculable human and political costs," alienated allies, and transformed Americans from liberators into a hostile occupying power, forced to rule Iraq with no exit strategy. His own son's folly had confirmed his wisdom, he felt.

But now his son had not only reversed his policies, he had taken things a step further. "The stakes are high ..." the younger Bush told reporters on April 21. "And the Iraqi people are looking -- they're looking at America and saying, are we going to cut and run again?"

The unspoken etiquette of the Oval Office was that sitting and former presidents did not attack one another. "Cut and run" was precisely the phrase Bush 43 used to taunt his Democratic foes, but this time he had used it to take a swipe at his old man. Having returned recently from the Masters Golf Tournament in Augusta, Georgia, the elder Bush was eagerly looking forward to his celebrity-studded birthday bash in June. But, to his dismay, the media didn't miss his son's slight of him. On CNN, White House correspondent John King characterized the president's speech as an apparent "criticism of his father's choice at the end of the first Gulf War." Thanks to a raft of election season books, the press was asking questions about whether there was a rift between father and son.

So on that brisk spring day, a friend of Bush 41's dropped by the Memorial Drive offices and asked the former president how he felt about his son's controversial remarks. The elder Bush was stoic and taciturn as usual. But it was clear that he was not merely insulted or offended -- his son's remark had struck at the very heart of his pride. "I don't know what the hell that's about," George H.W. Bush said, "but I'm going to find out. Scowcroft is calling him right now."

The battle lines between father and son had been drawn even before the Iraq War started -- a discreet, sub-rosa conflict that was both deeply personal and profoundly political. In the balance hung policies that would kill and maim hundreds of thousands of people, create millions of refugees, destabilize a volatile region that contained the largest energy deposits on the planet, and change the geostrategic balance of power for years to come.

Ultimately, it was the greatest foreign policy disaster in American history -- one that could result in the end of American global supremacy.

The two men shared overlapping résumés -- schooling at Andover and Yale, membership in Skull and Bones, and an affinity for Texas and the oil business. But that's about where the similarities end. From the privileged confines of Greenwich, Connecticut, where he was raised, to Walker's Point, the Bush family summer compound in Kennebunkport where his family golfed and ate lobster on the rugged Maine coast, to the posh River Oaks section of Houston after they settled in Texas, George H.W. Bush epitomized a blue-blooded, old money, Eastern establishment ethos that was abhorrent to the Bible Belt. By contrast, his son had been a fish out of water among the Andover and Yale elite, and scurried back to the West Texas town of Midland after graduating from the Harvard Business School. Nothing made him happier than clearing brush off the Texas plains.

People who knew both men tended to favor the father. "Bush senior finds it impossible to strut, and Bush junior finds it impossible not to," said Bob Strauss, the former chairman of the Democratic National Committee who served as ambassador to Moscow under Bush 41 and remained a loyal friend. "That's the big difference between the two of them."

More profoundly, they epitomized two diametrically opposed forces. On one side was the father, George H.W. Bush, a realist and a pragmatist whose domestic and foreign policies fit comfortably within the age-old American traditions of Jeffersonian democracy. On the other was his son George W. Bush, a radical evangelical poised to enact a vision of American exceptionalism shared by the Christian Right, who saw American destiny as ordained by God, and by neoconservative ideologues, who believed that America's "greatness" was founded on "universal principles" that applied to all men and all nations -- and gave America the right to change the world.

And so an extraordinary constrained nonconversation of sorts between father and son had ensued. Real content was expressed only via surrogates. In August 2002, more than seven months before the start of the Iraq War, Brent Scowcroft, a man of modest demeanor but of great intellectual resolve, was the first to speak out. At seventy-seven, Scowcroft conducted himself with a self-effacing manner that belied his considerable achievements. Ever the loyal retainer, he was the public voice of Bush 41, which meant he had the tacit approval of the former president. "They are two old friends who talk every day," says Bob Strauss. "Scowcroft knew it wouldn't terribly displease his friend."

Well aware that war was afoot, Scowcroft had tried to head it off with an August 15, 2002, Wall Street Journal op-ed piece titled "Don't Attack Saddam" and TV interviews. As a purveyor of the realist school of foreign policy, and as a protégé of Henry Kissinger, Scowcroft believed that idealism should take a backseat to America's strategic self-interest, and his case was simple. "There is scant evidence to tie Saddam to terrorist organizations," he wrote, "and even less to the Sept. 11 attacks." To attack Iraq, while ignoring the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he said, "could turn the whole region into a cauldron and, thus, destroy the war on terrorism." A few days later, former secretary of state James Baker, who had carefully assembled the massive coalition for the Gulf War in 1991, joined in, warning the Bush administration that if it were to attack Saddam, it should not go it alone.

On one side, aligned with Bush 41, were pragmatic moderates who had served at the highest levels of the national security apparatus -- Scowcroft, Baker, former secretary of state Lawrence Eagleburger, and Colin Powell, with only Powell, as the sitting secretary of state, having a seat at the table in the new administration. On the other side, under the younger George Bush, were Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, and Richard Perle, chairman of the Defense Policy Advisory Board Committee -- all far more hawkish and ideological than their rivals.

Of course, both Scowcroft and Baker would have preferred to give their advice to the young president directly rather than through the media, and as close friends to Bush senior for more than thirty years, that should not have been difficult. After all, Scowcroft's best friend was the president's father, his close friend Dick Cheney was vice president, and Scowcroft counted National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice and her deputy Stephen Hadley among his protégés. And James Baker had an even more storied history with the Bushes.

"Am I happy at not being closer to the White House?" Scowcroft asked. "No. I would prefer to be closer. I like George Bush personally, and he is the son of a man I'm just crazy about."

But in the wake of Scowcroft's piece in the Journal, both men were denied access to the White House. When the elder Bush tried to intercede on Scowcroft's behalf, he met with no success. "There have been occasions when Forty-one has engineered meetings in which Forty-three and Scowcroft are in the same place at the same time, but they were social settings that weren't conducive to talking about substantive issues," a Scowcroft confidant told The New Yorker.

Meanwhile, Bush senior did not dare tell his son that he shared Scowcroft's views. According to the Bushes' conservative biographers, Peter and Rochelle Schweizer, family members could see his torment. When his sister, Nancy Ellis, asked him what he thought about his son's plan for the war, Bush 41 replied, "But do they have an exit strategy?"

In direct talks between father and son, however, such vital policy issues were verboten. "[Bush senior is] so careful about his son's prerogatives that I don't think he would tell him his own views," a former aide to the elder Bush told New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd. When the Washington Post's Bob Woodward told Bush 43 that it was hard to believe he had not asked his father for advice about Iraq, the president insisted the war was never discussed. "If it wouldn't be credible," Bush added, "I guess I better make something up."

Likewise, friends who saw them together found that they had absolutely nothing to say to each other on matters of vital national importance. "I was curious to see how they related to one another, and I'll be damned," said Bob Strauss, who shared an intimate dinner with them in the White House. "They never discussed the war, never discussed politics. We talked about social things, friendships, what was going on back in Texas. It was like a couple of old friends just gossiping about the past."

Shares