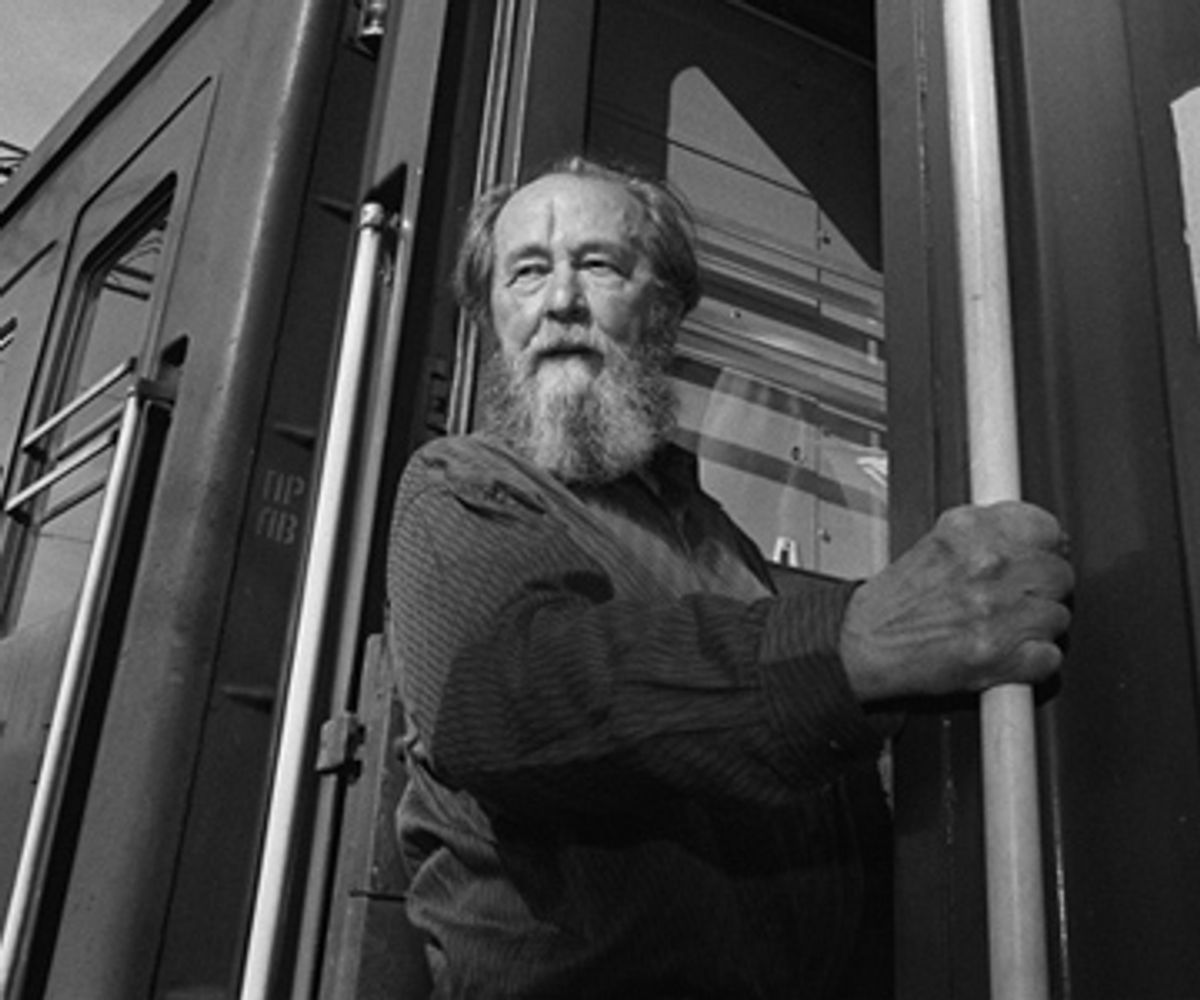

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who died on Aug. 3 at the age of 89, was, by most accounts, a difficult man. His sizable oeuvre, urgent and prophetic in its condemnation of communism, left little room for moral inaction; he spent nearly two decades in the United States, but the comforts of America also disgusted him. And when he returned to his homeland in the 1990s, its headlong rush to materialism -- a McDonald's in Moscow! -- offered a jarring contrast to the image of Holy Russia that had so long beguiled him. In the end, one gets the sense that the modern world disappointed Solzhenitsyn so thoroughly that he could only find refuge in words from which he fashioned a country -- an agrarian, God-fearing Russia -- scrubbed free of the distasteful century into which he was born.

The nearly 30 works he published were instrumental in bringing the Soviet Union to its knees, but none struck as deeply as his first, a slim volume called "A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich." Its author was an artillery officer who, during World War II, had depicted Stalin unfavorably in a letter to a colleague, earning himself an eight-year sentence in a labor camp. In the camp he survived his first bout with cancer; then, facing internal exile in the outer reaches of the empire, began to write of his experiences while teaching science at a high school, guided by Dostoevski's insight that "beauty will save the world."

One could argue that "Ivan Denisovich" is not a beautiful book, since it lays bare, more than anything, how ordinary cruelty becomes when applied on a large enough scale. It is not terribly intricate, either: Ivan Denisovich Shukhov, a prisoner in a Soviet labor camp, wakes up late one morning and spends a day facing the indignities inflicted by his guards, fellow prisoners and freezing temperatures, spurred onward only by the animal need to survive. Unlike other critiques of the Soviet state, such as Mikhail Bulgakov's "Master and Margarita" or the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, it did not disguise its condemnation of the Bolshevik regime in fantastical prose or historical reference. Solzhenitsyn sensed, instead, that the mere reporting of things as he had seen them would shake the Kremlin to its core.

But even he could not have expected the reception that would result from Alexander Tvardovsky's desire to include his manuscript in the Novy Mir (New World) magazine in 1962. The ultimate decision to publish "Ivan Denisovich" would come not from the Novy Mir editorial offices but Nikita Khrushchev himself, who was desperate to distance himself from the unbridled cruelty of the Stalin years. In allowing for the publications of Solzhenitsyn's debut, Khrushchev not only tacitly admitted to the existence of the gulag system of concentration camps but engendered a national conversation -- whispered but pervasive -- about how a state supposedly governed by common men and women could imprison and kill so many with such efficient ease.

Publication made a subversive hero of Solzhenitsyn, but he wanted only to continue writing, feeling that he must speak for the millions still silenced in the frozen plains of Siberia. As the brief liberalizations of the Khrushchev era faded, Solzhenitsyn faced unceasing harassment from a rejuvenated KGB, eager to punish the pious dissident. His manuscripts -- treated like holy relics by those charged with their safekeeping -- were seized, and he was not allowed to travel to receive the 1970 Nobel Prize in literature, which his detractors perceived as little more than a cruel jab from Europe at Moscow. Forced out of Russia in 1974, Solzhenitsyn finally claimed his prize in Stockholm, Sweden, declaring that he was "cheered by a vital awareness of world literature as of a single huge heart, beating out the cares and troubles of our world."

"Ivan Denisovich" was just the start of a literary career that would cover four decades: "The Gulag Archipelago" left no doubt about the bedrock of political terror on which the Soviet Union rested, while "The Red Wheel" treated Russian history with the epic scope and grand moral concerns that had once been the domain of Tolstoy and Dostoevski. Yet nothing approached the power, page by page, of the straightforward account of Ivan Denisovich Shukhov, the wearied prisoner who wants badly to avoid a day of work out in the cold. His fate, at once horrible and quotidian, gripped the national imagination with such ferocity that the Communist Party was soon fighting a rising tide of writers who wanted to write about the gulags and little else.

The camps are long gone, but journalistic responsibility remains. Countless journalists have been killed in Russia for following in Solzhenitsyn's path, for reporting honestly on the war in Chechnya and the restriction in civil liberties that unsurprisingly followed. Solzhenitsyn survived imprisonment, harassment and exile; today, a Russian journalist worth her salt can expect to be thrown from a window, shot in an apartment lobby, kidnapped and never seen again. Such, tragically, is the legacy of a science teacher from Ryazan who never wavered from the belief that the writer is "an accomplice to all the evil committed in his native land or by his countrymen."

But even Solzhenitsyn had his blind spots. Despite a moral vision deeply informed by the Russian Orthodox tradition, he did not have the all-embracing vision that allowed leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. to transcend the constrictions of race, class and nationality. His fulsome criticism of the West and its "irresponsible" freedoms smacked too strongly of fundamentalist enmity; far uglier are the intimations of anti-Semitism that appear in late works like "Two Hundred Years Together," which hints without much subtlety that Russia would have been better off without its Jewish citizens. Returning to Russia in the 1990s, Solzhenitsyn quickly wore out his welcome through vitriolic attacks on the fledgling democracy that could have been delivered at a less tender time. Yearning for the Russia of "War and Peace," he seemed out of place in the Wild East ushered in by Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin.

But there is still the matter of Ivan Denisovich, trudging through his day, subject to the outrageous fortune inflicted upon so many of his compatriots. His creator may not have been an agreeable man, but it was only because he burned with a vision so fervent that it left no room for anything but the most difficult questions a man, and his nation, could face. In that November '62 issue of Novy Mir, an entire nation awoke with Ivan Denisovich.

Shares