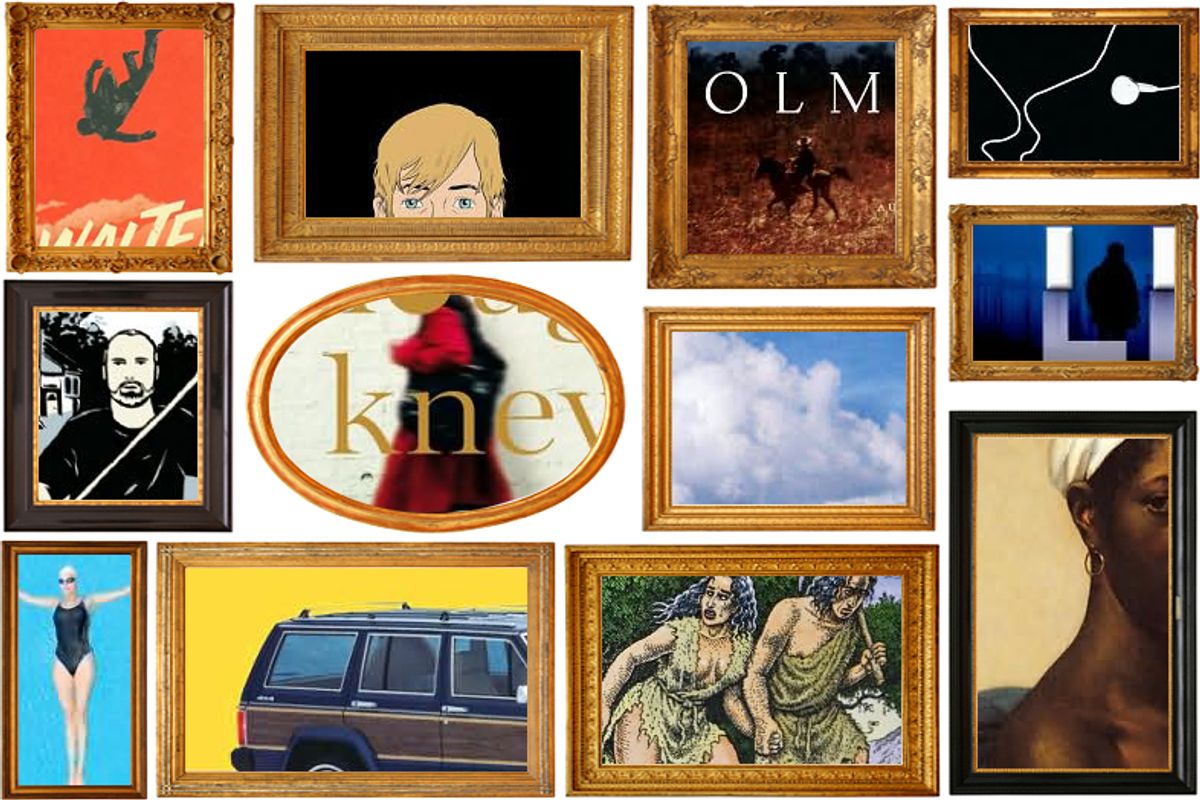

Nick Hornby, the author of "Juliet, Naked"

Jess Walter is one of your country's most interesting younger novelists, and one of my favourite contemporary writers. And his latest book, "The Financial Lives of the Poets," seems to me to contain most things that one can reasonably expect from a good novel: It's wise, moving, very funny and timely, dealing as it does with economic calamity and how that whole mess impacts our lives and relationships and souls. Oh, and it's a joy to read, too — a sine qua non, given the darkness of the times, both within the book's pages and out here in the world.

Judy Blume, children's book author, most recently of "Soupy Saturdays With the Pain and the Great One"

What I look for, what I always hope for, especially when I pick up a first novel, is an original voice. In Nicola Keegan's "Swimming" I found not only the most original voice I've read in a long time, but a fantastic story of one girl's journey from splashing infant to Olympic champion. But it's not really about those gold medals. It's about a life, it's about a family — and what a family! Not that any of it is what you expect. That's the thing about this book. It's never what you expect. You know how the best fiction plunges you deep into another world? I would happily have stayed in Pip's world.

Come to think of it, it's time for me to read "Swimming" again. And no, Nicola Keegan was never an Olympic swimmer. But she sure fooled me. Kind of the way Wally Lamb fooled me in his first book, "She's Come Undone." I was convinced when I finished it that Wally was a woman. Had to be a woman. If you enjoy books and movies that make you work, you won't be disappointed. And you'll come away wanting to know everything you can about Nicola Keegan, especially when we can read her next book.

Anne Lamott, author of "Grace (Eventually): Thoughts on Faith"

One book I loved this year was "What I Thought I Knew" by Alice Eve Cohen, a memoir of an impossible and misdiagnosed pregnancy by a mother (already in her 40s) with a much younger man, and the ultimate knowledge that the fetus had Major Issues. It is just lovely, everything we love in a book -- profound, honest, hilarious, humane, surprising. It's the book I foisted on everyone.

Matthew Klam, author of "Sam the Cat: And Other Stories"

"Lowboy," by John Wray, is a really tight thriller and love story told in short scenes about a young man who believes that in 10 hours global warming will destroy the world unless he (and only he) does what he believes he must do to stop it. It's an amazing view of city life as seen through the eyes and the wanderings of a schizophrenic young man with a history of violence, off his medications and hiding out in the sewers and subway tunnels of New York. In "Lowboy," Wray is so deeply living inside his work that it hums and shivers, echoes and drips with authentic believable and gorgeously wrought dialogue and scenes. Wray etches his details and inhabits all nature of humanity with ghostly power and can surely see up his characters' noses, can see the geography of their tongues. This is a sometimes light, sometimes horrifying, pitch-perfect and lovingly rendered thing.

Junot Diaz, author of "The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao"

Here's a I book I fought hard for during the National Book Award judging, but to no avail: Chloe Aridjis' "Book of Clouds." A hypnotic first novel about a young Mexican gal in Berlin who stumbles into friendship with an eccentric historian and the madness that ensues. This book has the power of dreams and still hasn't left me.

Lydia Millet, author of "Love in Infant Monkeys"

Robert Olmstead is one of the most sublime novelists we have. His work is under-recognized, I suspect, because his subject matter — Western and violent and horsey and manly — shares some ground with the better-known and highly talented Cormac McCarthy, and possibly there isn’t enough room in the culture for both of them to be famous at the same time. But to my mind Olmstead is the even greater artist and the more compassionate of the two writers; his style is more restrained, his language more perfect.

"Far Bright Star" tells the story of some brothers on horseback and some people who die — its set in 1916 during the search for Pancho Villa, and the plot has to do with revenge and is full of death and solitude. I’m purposefully vague here because in the end I didn’t much care about the details of the story, though in fact the narrative was well-crafted in its rhythms and suspenses. Rather I was repeatedly startled and taken in by the raptures and ecstasy of the prose, its philosophical qualities, its space and imagination and sculptural beauty and terrible sadness.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of "The Thing Around Your Neck"

I deeply admired the talent, ambition and courage it must have taken to write "Zeitoun." Dave Eggers has appropriated — in the best possible sense — the story a Syrian-American family’s experience of Hurricane Katrina. His writing is spare and precise, with respect for both the reader and the story, and underlying the narrative is a wonderful sense of outrage made all the more powerful because of how light his touch is.

Juan Cole, author of "Engaging the Muslim World"

My pick for 2009 is Barry Eisler's "Fault Line." Eisler has reinvented the spy thriller for the 21st century. His fast-paced plots and action sequences are not slowed down by his careful exploration of moral ambiguity and the space he gives his characters to develop. His Iranian female lead is smart, frighteningly competent and creamily gorgeous. His tough-guy protagonist, Ben Treven, can take down Russian mafiosi in a nanosecond but can’t escape the legacy of family tragedy. Treven lives the contradictions of our time -- the fight against terrorism and the outrage against torture, the need for ruthlessness and the perdurance of American values, the patriotic commitment and disillusionment at the betrayals of our leaders. Eisler’s ability to write both as an intelligence insider and a perceptive social critic allows him to create a gripping and believable universe in which you would just remain if only the book wouldn’t end.

Colum McCann, author of "Let the Great World Spin" and winner of this year's National Book Award for fiction

It's impossible to pick an absolute favorite -- there are so many -- but one book that I think deserves a very loud shout-out is "The Book of Night Women" by the young Jamaican novelist Marlon James. It's a slave narrative, a story of rebellion, beautifully written, brave, smart, incisive and, yes, even funny. James has been called "a Jamaican Diaz" -- it's a nice phrase, and it also happens to be true.

Laura Lippman, author of "Hardly Knew Her"

By this point in my reading life, I have two mantras: "Surprise me" and "Have a take and don't suck." Jim Rome coined the latter, but the former is the result of more than a decade as a crime novelist. I'm a hard reader to surprise. I'm not talking about traditional plot twists, but something almost indefinable, a resolution at once true and earned, yet not entirely expected. In Jess Walter's fifth novel, "The Financial Lives of the Poets," he sets up a hilarious situation -- former reporter/would-be Internet entrepreneur decides to become a pot dealer to forestall his family's financial crisis -- and brings it to a ruefully understated ending. Bonus: A succinct and, yes, poetic description of what's happened to newsrooms over the past few years. It actually reminded me why I loved being a newspaper reporter, once upon a time.

Amy Sohn, author of "Prospect Park West"

Sparer than some of his other books, fast-paced and full of heart, Nick Hornby's "Juliet, Naked" centers on the relationship between Annie, an emotionally adrift English woman of 39 -- and the reclusive Bob Dylanesque musician Tucker Crowe, who her boyfriend has idolized for years. The proscriptive fan boy is a Hornby archetype ("High Fidelity"), but here he shows the darker side of this personality: zealous narrow-mindedness and a total lack of generosity.

The real triumph, though, is the protagonist, Annie. Hornby has always been good at writing women, but Annie is his richest female character to date -- a woman of childbearing age (just) who wakes up one day and realizes that 15 years have passed without her getting anything she wants. There's also a hilariously inept shrink and a perfectly pitched 6-year-old boy. This book, combined with Hornby's screenplay for "An Education," which focuses on a 16-year-old schoolgirl in early-'60s London, work well together as a dual portrait of lost women at different stages of life.

Sean Wilsey, co-editor of "State by State: A Panoramic Portrait of America" and author of "Oh the Glory of It All"

I'm not always a fan of the memoir. But "The Kids Are All Right" reinvents the genre. It's a choral book, with the point of view shifting between four siblings -- Amanda, Liz, Dan and Diana Welch -- who recount, and disagree about, the disintegration of their family. After their father's sudden death in a car crash comes their mother's slow death from cancer, and then the narrative explodes into pure bedlam: children on their own! The setting is suburban New York and Manhattan, and the time is the '80s, in all their forgotten glory -- no clichés, just detail after detail that eerily reconjured my own childhood in cars, TV, music, products, as I'd long since forgotten it. This is a memoir that always feels alive and true, and one that exists for no other reason than that the story needed to be told.

Maud Newton , books blogger

My favorite book published this year was also one of the most disillusioning. R. Crumb's "Book of Genesis" combines the fire-and-brimstone flavor of Jack Chick's fundamentalist tracts with peerless artistry and painstaking attention to historical detail and produces a straightforward but incredibly immersive retelling of the first book of the Old Testament. "The Bible doesn't need to be satirised," Crumb has said. "It's already so crazy." In relying on Robert Alter's (very thoughtful) translation, though, Crumb casts doubt on my longtime admiration for Eve, who in some renderings chose to eat of the fruit of the forbidden tree because the serpent convinced her that it was "desired to make one wise."

Contemplating this rationale for a Bible as Literature class years ago, I concluded that God excoriated Eve more roundly and punished her more severely than he did Adam not because she was more wicked, but because she represented an actual threat. Seeking knowledge, she chose to eat the fruit, whereas Adam ate passively and only because she handed the fruit to him and had tried it first. Adam would never of his own accord betray or compete with God the way Satan had. Eve, on the other hand, aspired to be godlike. Crumb's rendering of my hero doesn't support this reading, however; he ascribes her actions to the temptations of the serpent and emphasizes only that the fruit was pleasing to the eye.

Tracy Kidder, author of "Strength in What Remains"

I think my favorite book of 2009 is Alice Munro's new collection of stories, "Too Much Happiness: Stories." I've long admired her writing. I think she's one of the best writers alive. I'm not sure there's much more to say.

Dave Cullen, author of "Columbine"

I loved the idea of "Sum: 40 Tales From the Afterlives," but did I actually want to slog through 40 of them? How many novel conceptions of the afterlife are there -- wouldn’t this be about 35 too many? No, actually. David Eagleman has got a million of them.

Eagleman did his undergrad in literature and his Ph.D. in neuroscience. He runs a brain lab by day and writes fiction at night. It shows. His provocative little vignettes play like brainstorms between alien hemispheres: playful, intriguing and full of emotional surprises as well as ideas. When his over-specific gods in charge of spoons, bacteria and chewing gum look down at our traffic jams and find comfort in our disarray but also our desire to reach out to find comfort through a cellphone ... there is tenderness here, and perception, too.

The conceit is different, but the effect kept summoning up the delightful "Wearing Dad's Head." No one has ever reminded me of Barry Yourgrau before. I never thought they would.

I’m still making my way through Jeannette Walls’ "Half Broke Horses," loving every sentence of it. I felt Texas from page one, and Texans, who I couldn’t wait to know better. Her style recalls, lovingly, the late great working-class short-story teller Lucia Berlin. I’m taken, particularly, by Walls’ ability to write children: not book children, or film kids -- actual mini humans with the complexities of their parents, and even less predictable.

Geoff Dyer, author of "Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi"

It’s been a great year for fiction and nonfiction alike, but for sheer page-turning excitement, knowledge-gained per page turned, and sustained admiration for what the writer was doing, I will go for Richard Holmes' magnificent "Age of Wonder." I should have added, as well, that it’s an incredibly original idea: a biographical relay in which the baton of scientific exploration is passed from Joseph Banks in Tahiti in 1769, to William Herschel and his sister at their telescopes, to Humphry Davy in his lab (yeah, I know, I didn’t have any particular interest in this stuff either) and beyond. Set against a blazing firmament in which the great stars of the Romantic movement are plainly visible, it’s a flat-out masterpiece of historical and biographical narrative.

Curtis Sittenfeld, author of "American Wife"

The book I'm obsessed with right now is "Tinsel: A Search for America's Christmas Present" by Hank Stuever. Stuever is a Washington Post reporter who spent the 2006 Christmas season following three people in Frisco, Texas, a wealthy suburb of Dallas: One is a single mom who's very involved in her megachurch, one is the guy who lives in a house that's decked out with a billion Christmas lights (and it turns out he's more tech geek than Christmas diehard), and one is a simultaneously savvy and un-self-aware woman who decorates other people's McMansions for the holidays.

Stuever, who is something of a Christmas cynic, spent months with these people, and he shows them in all their glorious, complicated humanity. I love this book so much that I've literally bought seven copies (so far) to give as gifts, which is to say I've broken the personal record I set in the mid-'80s for giving the same present to the maximum number of people -- back then, all the members of my family were recipients of identical reindeer ornaments made out of clothespins. I like to think my taste has improved in the last 25 years.

Shares