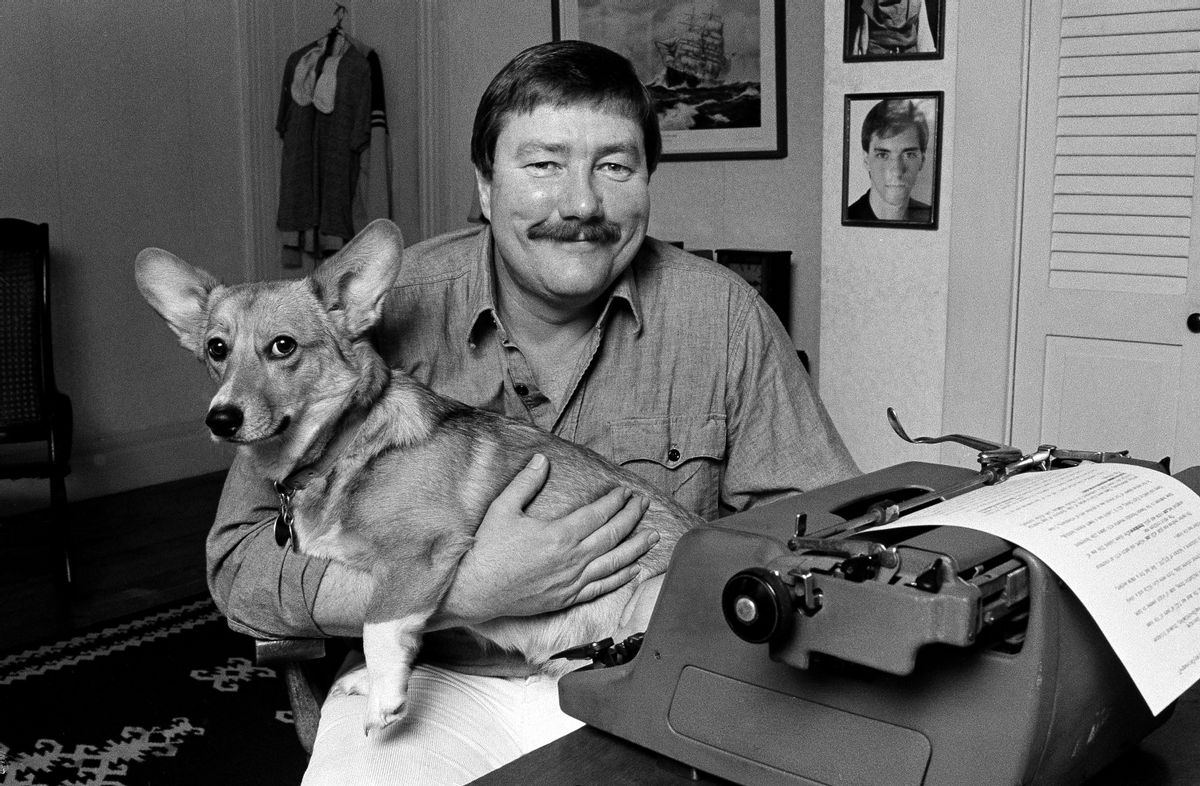

A version of this story first appeared on Steven Axelrod's blog.

Robert B. Parker taught my son to read.

OK, that's a slight exaggeration. He didn't sit with Nick and sound out the vowels and work on the phonics textbooks. But he made Nick want to read and that's more important than all the vocabulary tests and grammar lessons put together. I gave Nick "Mortal Stakes," "Looking for Rachel Wallace" and "Early Autumn" when he was in eighth grade. Up until that moment he had never read a book for fun. Schools aren't too big on fun, and don't seem to understand the carnal pleasures and quiet consolations of a good book, whether you're waiting on line for a movie (I read "Schindler's List" waiting to see "Jurassic Park" -- thanks, Steve), or waiting for your father's funeral, which is when I burned through the Harry Potter books available at the time.

It was my dad who gave me my first Robert B. Parker Spenser novel, "Taming a Seahorse." I had just landed at LAX after a long plane flight from New York. He handed me the novel and said, "This will take care of your jet lag."

Dad loved Spenser's tough, unsentimental style and his dry wit.

I remember Spenser correcting an unamused thug who had just remarked that "Everybody's a comedian," noting, "You haven't said anything funny." Threats like "I'm going to kill you" were always met with a precise and ironic "You're going to try." When Spenser goes back to the crippled billionaire whose family's murder he avenged in "The Judas Goat" to ask for money so he can rescue Hawk in "A Catskill Eagle," the old crank is amused by Spenser's casual admission that his only interest is money and Spenser's complete failure to suck up to him during the intervening years. Spenser never schmoozed and he never faked it. Some friend of Hawk's once asked him, "What do you see in that big white guy?" And Hawk replied, "He does what he says he's going to do." For Spenser that constitutes a whole philosophy of life, but I remember thinking at the time -- "That's it? What's the big deal?"

That was before a thousand missed appointments and a dozen fizzled partnerships, before a hundred letdowns, big and small -- many of them with me at fault. Gradually, I learned the depressing, repetitive fact of life: Almost no one actually does what they say they're going to do. I try to do it, as I try to live up to Spenser in so many ways. You could have a worse role model, though not a more exigent one. Spenser does things his own way. In "Early Autumn," he's hired to find a runaway boy. He tracks down the kid easily, but soon realizes that the parents are monsters and the boy, one Paul Giacomin, was right to run away. Instead of returning the spoiled, petulant little creep, Spenser takes him out to some land he owns in Maine and builds a house with him. He teaches Paul construction and fighting, the two things he knows best, and the kid turns out all right. In later books he becomes a ballet dancer and remains a true friend over the decades. Paul is just one member of the extended Spenser family.

When Spenser takes the job of protecting radical lesbian Rachel Wallace, he strong-arms some security people. They were trying to forcibly remove her from a political demonstration, and she wanted to be manhandled out of the place, to make a political point. She fires Spenser ... and then gets kidnapped. Spenser finds her on his own, for no pay, out of simple remorse and obligation. Rachel Wallace continues to appear in later books, as does Patricia Utley, the high-class madam we first meet in "Ceremony." Lawyer Rita Fiore, gangster Gino Fish, local cops Belson and Quirk are among the many other regulars in the books.

And then there's Hawk, cool, impeccably dressed Cristal-drinking leg-breaker and equal member in Spenser's freemasonry of American manhood. He doesn't talk much, but he and Spenser understand each other. They are two Quixotes, cleaning the street gangs out of a Boston housing project for no money, making jokes about doubling their fees next time. Spenser is cool but Hawk is the coolest. Who can forget that scene in "A Catskill Eagle" where Hawk arm-wrestles some hulking mercenary in a bar, letting the guy press his arm to within an inch of the tabletop, stopping him there and then -- when Spenser indicates that they have to go -- effortlessly snapping the soldier's arm in a 180 degree arc and slamming it onto the table.

Of course the primary member of the Spenser family is Susan Silverman, his gorgeous shrink girlfriend. I have to say I've never been overly fond of Susan. She thinks too much and she's a little self-conscious. Also she eats like a bird. Driving down Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood years ago I saw a bumper sticker that said "I'll be your Susan if you'll be my Spenser." I pulled up next to the woman at the red light on Fairfax and rolled down my window. "You have a problem," I said. "Susans are everywhere. But Spensers are hard to find." She shrugged. She knew it, much better than I did. Oh well, there was always the next Spenser book.

Until today.

All we can do now is go back and reread them, along with the other great books, "All Our Yesterdays," his Boston police epic; "Wilderness," his thriller-writer-witnesses-a-mob-hit-and-finds-himself-living-one-of-his-own books adventure; and of course his glorious, late-career western trilogy ("Appaloosa," "Resolution," "Brimstone") with Spenser and Hawk reimagined as itinerant gunmen Everett Hitch and Virgil Cole.

Parker taught me to appreciate scotch and soda, stand up to bullies and finish the extra set of sit-ups. He taught me how to make a fast meal and break into a window by chipping out the glazing. He taught me that solving a case has more to do with poking at a situation waiting for things to happen than finding clues. He made Boston appealing (even without a GPS). More than that, he made adulthood appealing, for three generations of my family -- my brilliant, alcoholic father, my hesitant pre-adolescent son, and me. Someone once remarked that I was always in search of father figures. Maybe it's true. I know I lost another one on Monday morning.

He died at his desk, writing, That's the way any writer would want to go. The police said there was no sign of foul play. That was oddly disappointing, a brackish dousing of reality. A writer found dead at his desk in a Parker novel would spark another fascinating case for Spenser and Hawk. Susan would chime in with the psychiatric angle: an angry editor? A pathological fan? A jealous mystery writer? They would track it down, between runs along the Charles and workouts at Henry Cimoli's regrettably gentrified gym. (It has potted plants now.)

This is real life, though -- and Parker is just gone. But his people remain, caught in time, unfaded, reliving their adventures, forever.

Parker taught my son to read; I suspect he'll be teaching my grandson, too.

Shares