A version of this post previously appeared on The Biblio Files blog.

If you listen to an audiobook, have you read the book?

It's undoubtedly a different experience to read a book with just ink and paper (or pixels and screen) between you and the author, than it is to listen to someone's vocalization of the sentences. In "Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain" author Maryanne Wolf describes how the brain processes written information differently than audio or other information. Stanislas Dehaene delves even further into the science of reading in his book "Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention

." Listening or reading? It seems like an academic question. What difference does it really make? But a couple of articles I read recently have made me wonder.

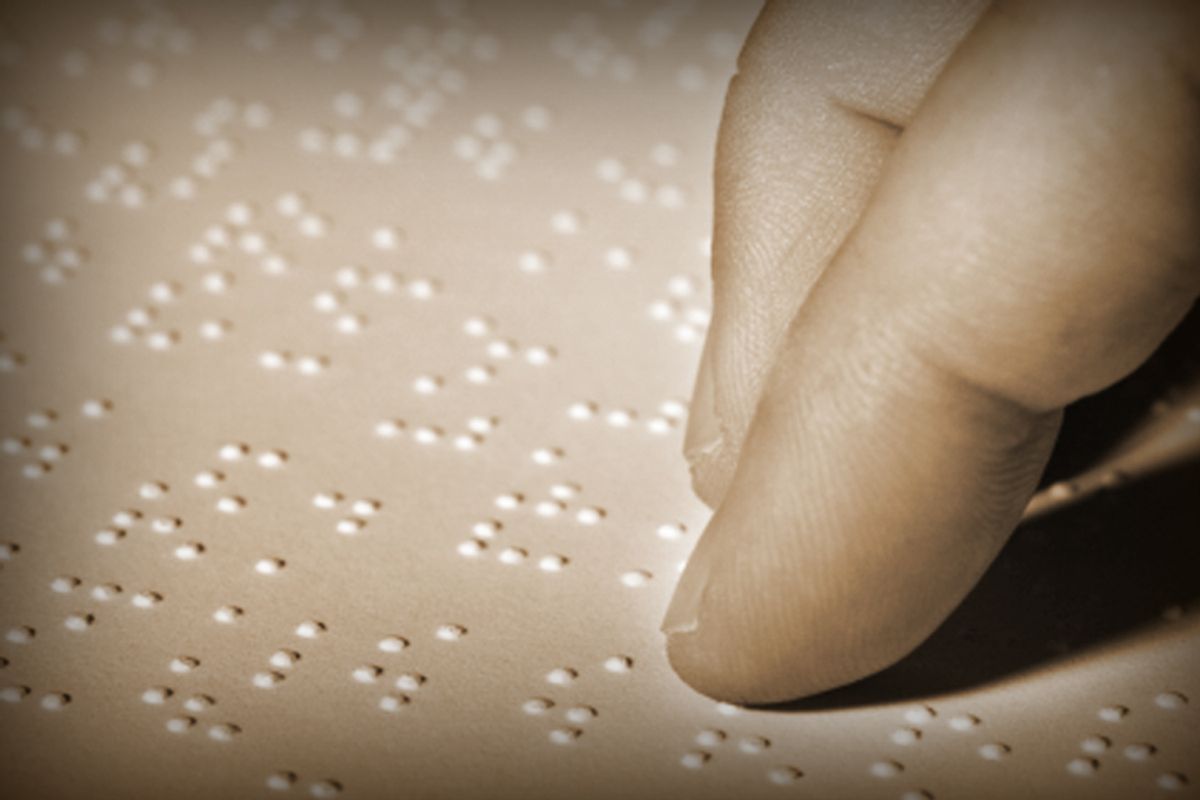

In this New York Times article, we find that many blind people, including the governor of New York, don't read braille. Instead they rely on audiobooks, recordings of newspapers and magazines, and human assistants to orally brief them on the business of the day. Text-to-speech technology allows people to hear their e-mails and other documents.

And in this Canadian Broadcasting Corp. article, we find that the major provider of books in braille in Canada is about to go out of business if it can't get government funding or some other source of revenue. They are having a hard time convincing people that braille is even necessary anymore.

In the New York Times article, one advocate for the disabled characterizes blind people who don't read braille as illiterate. He describes their writing as "phonetic and butchered." If it were merely a matter of acquiring information, as seems to be the case with the woman profiled in the New York Times, then there's no doubt that the quickest, most efficient method of “reading” is preferable.

I can't help thinking that it's a mistake to let braille die, though. According to the National Federation of the Blind, only 10 percent of blind children learn braille today, down from 50 percent in the 1950s, and only 10 percent of blind people in America read braille. Is it just as good to listen to a book as it is to read it? When I listen to a book, my mind wanders more often than it does when I read a book. If I want to read faster or slower, it's up to me, not the person who is reading (although there are audiobooks now with adjustable speeds). My brain seems more passive when I'm listening than when I'm reading, but that could be a lack of mental discipline on my part.

Human beings have been talking and listening to each other for at least 50,000 years. We've been reading and writing for around 7,000 or 8,000 years. People don't have to be taught to listen. Reading is a different, more complex activity than listening.

Don't get me wrong -- audiobooks are great for car trips or when you're in the gym. Multitasking dynamos like Gov. Paterson and others, blind or not, find audiobooks and other recorded documents an efficient way to acquire information. You have to admire that.

But listening isn't reading. I hope that braille instruction and braille books remain an available option for people who can't read print.

Shares