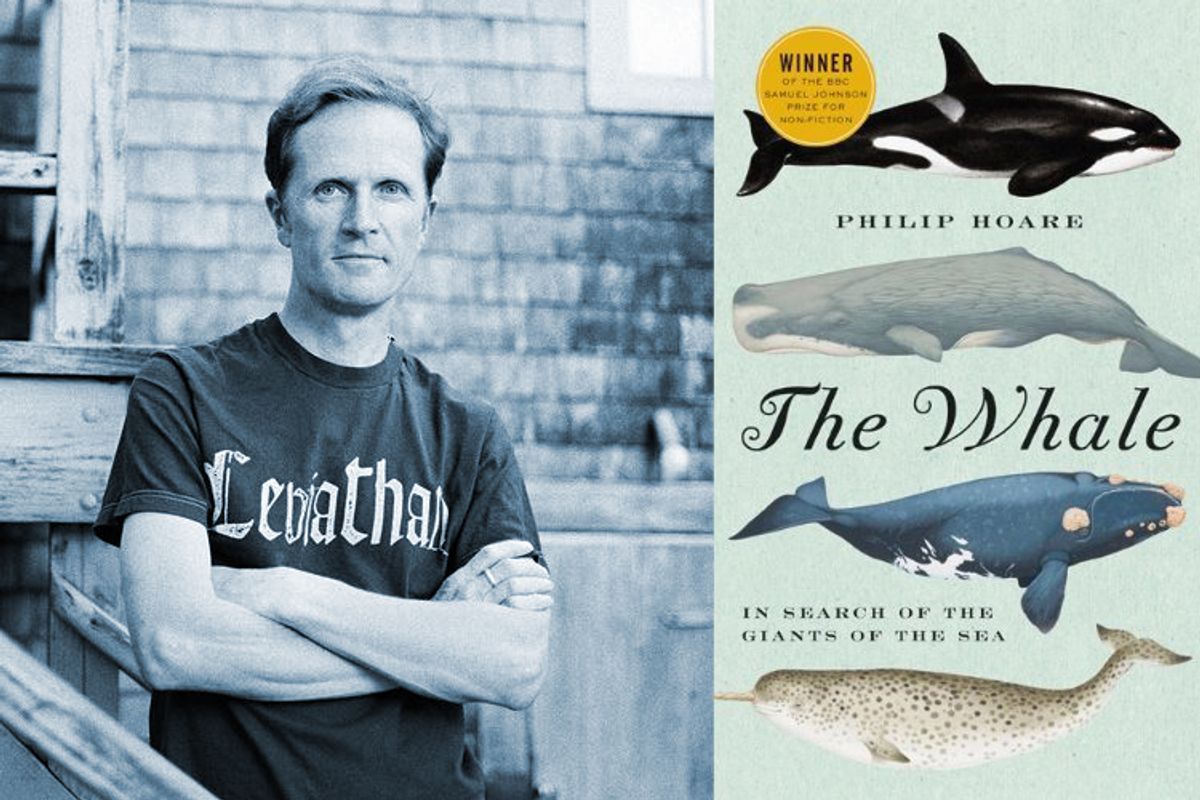

"To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme," wrote Herman Melville in "Moby-Dick." So to choose as one's theme both whales and the greatest book ever written about whales — as British writer Philip Hoare has done in "The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Sea" — would seem to ensure some mighty reading material.

"The Whale" does not disappoint. First, there are the simple, shocking facts about whales. A fin whale off the coast of Nantucket can be heard by its counterpart off the coast of England, about 3,000 miles away. Inuit harpoons dating back 235 years have been found in the belly of hunted bowhead whales — one of the world's longest-living mammals. The right whale is the owner of the largest testes in the animal kingdom (around 1,100 pounds each), and, after foreplay sessions involving sensuous flipper stroking, the female may let more than one partner enter her at the same time.

Hoare, drawing on his experience as a biographer of Noël Coward and Stephen Tennant, the outrageous British aristocrat, interweaves these facts with revelatory glimpses into Melville's life as he contemplated and composed "Moby-Dick." More importantly, he delves into his own psyche in an attempt to understand our species' long-standing fascination with these leviathans of the deep. In a hilarious and moving climax — or, as Hoare's friend John Waters puts it, "orgasm" — the author, a recovering aquaphobic, finally dives into the ocean to swim with a giant sperm whale.

Salon spoke with Philip Hoare in the lobby of the SoHo Grand Hotel in Manhattan, where he touched on the gayness of “Moby-Dick,” John Waters' fear of the sea, and why it might be time to stop fighting Japanese whalers.

How did you come to write a book about whales?

My first two books were fairly straightforward biography. But gradually my work became more digressive, and I was introduced to W.G. Sebald, who wrote me this amazing fan letter. It was like getting a letter from E.M. Forster or something. So we had a kind of correspondence, but he died shortly thereafter. Then my mother become ill, and I found myself retracing my life in a way. I'd been deeply interested in whales as a boy and felt this retreat back to the sea. I started swimming every day. And when John Waters invited me out to Provincetown — he’d reviewed my first book, and I’ve known him since 1991 — a whale quite literally swam into view during a whale-watching trip.

So you and John Waters go whale watching together?

Are you kidding? You would never get John on a boat or anywhere near a whale. I show him my photographs of whales, and he says, "That’s just whale porn." He accused me of being a whale stalker. But he’s a real inspiration. He said, "You’re spending more time with whales than you are with human beings, you’ve got to do something about it." I didn’t know how or if I could, but emboldened by Sebald, I just put a bunch of things together. So the book’s got two godfathers, I suppose: W.G. Sebald and John Waters. Bizarre pairing, isn’t it?

Why do you think whales continue to have such a hold on us, especially in the arts?

We live in the same world as whales, yet we might be on entirely separate planets. They ought to be grotesque, yet they are unutterably beautiful. I've stood next to grown men in tears at their first sight of a whale. To have the ocean thus animated is almost too much. We don't deserve whales. I guess that's the bottom line.

One young female artist in London said to me recently that the whale is the perfect muse. It is blank canvas on which an artist can project her or his ideas. It can withstand any amount of interpretations and at the same time reject them. It's wreathed in myth and mystery, yet exists in reality. It defies all representation — "the living leviathan never fairly floated itself for its portrait," as Ishmael said. Such defiance is tantalizing to an artist, as much as it is to a writer.

Japan, Norway and Iceland are the only whale-hunting countries left, Japan being the most notorious. Why do they keep hunting whales, when all they're really used for anymore is meat?

There’s a lot of political and historical context here. Gen. MacArthur advised that the decommissioned Japanese Navy be turned into a whaling fleet after we bombed Japan in World War II. And when the international moratorium on whaling was about to be introduced, the U.S. specifically said to Japan, "If you stop whaling, we will allow you an unlimited quota to fish within U.S. waters." It was a direct deal done with the U.S. government. This was in the '70s and early '80s. But soon, the quota was halved, and a year or so later completely withdrawn. This is just a political detail, but it’s one of the reasons the Japanese feel so politically undermined and affronted by the whaling issue.

The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society was recently in the news when their very expensive Batmobile-like boat, the Ady Gil, flying the skull-and-crossbones, collided with a Japanese whaling ship. What do you think of the group's tactics?

There are lots of problems with the opposition to Japanese whaling. I was a very radical political activist in my time, and I would still consider myself to be so. But Sea Shepherd's emotions seem to be getting in the way of the pragmatic reality of the situation. I find it very arrogant and hubristic, decorating one's boat to resemble the Batmobile, for instance. Capt. Paul Watson, the founder of Sea Shepherd, is like this modern Ahab.

I was recently in Tasmania and met one of his acolytes — it was like meeting someone from Jonestown, from a cult. The Red Hot Chili Peppers and Trudie Styler, Sting’s wife, give money to Sea Shepherd, because it’s a popular cause. And for good reason — the punk in me agrees with the gesture in a way. But I wonder whether it’s doing whales a disservice, being so confrontational and potentially undermining the political dialogue. It might just be the awful compromise that we have to allow Japan to hunt whales in coastal waters.

For a long time, we didn't really know what whales really looked like. Underwater photography didn't really come into use until the 1960s. How did that change our relationship to whales?

It showed them to us. We knew what the world looked like from outer space before we knew what sperm whales looked like underwater. How they move, how they behave. It's a symptom of how little we know, of what infancy cetacean science finds itself in. As simple a matter as the way a whale calf suckles from its mother, for instance: Do they use their nostrils or their mouths? It's a basic fact of natural behavior — yet we still aren't sure. Of course in seeing whales, whales see us. We change their world by entering it. For centuries whales knew humans only from above. Now they experience these extraterrestrials descending upon them. I might turn the question around and ask, what effect does that have on them?

"Moby-Dick" seems chock-full of subtle and not-so-subtle homoeroticism. Do you think this was intentional on Melville's part?

It is no coincidence, I would contend, that Melville's most famous work is called "Moby-Dick." One entire chapter, "The Cassock," is devoted to the whale's foreskin. Melville undoubtedly portrays the entire animal in a phallic manner. It is also, as we would now see it, itself the shape of a sperm. After all, it gained its name from the fact that the hot oil from its nose turned cloudy as its head was pierced — early sailors believed this to be the animal's semen; hence its name.

"A Squeeze of the Hand" must be one of the most homoerotic passages in 19th-century fiction — the scene in which the whalers sit around a vat of spermaceti, squeezing out the lumps. Ishmael rhapsodizes on the accidental contact with other men's hands in the oily mélange. It's virtually a circle jerk. Melville makes many other references to male love in his work. Yet I'm at pains not to reduce Melville's story to the idea of reclaiming him as a gay writer. I kind of don't believe in gay writers. No one describes Charles Dickens as a straight writer.

At the end of the book, you finally jump into the water with a giant sperm whale. What was that like?

Normally you see the whale from the surface of the ocean, or dead, or mediated. So going into the world of the whale was a complete mindfuck. I felt slightly insane, partly because of its sonar echo-locating my skeleton. It’s a powerful electrical charge going through your body; you feel this 3-D image of yourself being relayed back to the whale, much as you might see your reflection in the mirror. And yet it’s entirely silent.

This female whale eyeballed me and then jack-knifed through the blue into the black. It was just so improbable. It’s like a CGI re-creation of a whale. It’s almost laughable. For three days afterward I’d close my eyes and this whale would swim through my head. At that range, you can just tell they’re sentient, intelligent animals. I felt like I ought to apologize to it for the weight of history I’d brought with me into the water.

Shares