To most Americans the idea of an arranged marriage sounds not only bizarre, but fundamentally wrong. How could you let someone else decide the person you're going to be spending the rest of your life with? But as Sheena Iyengar describes in her new book, "The Art of Choosing," arranged marriage has been the norm in many parts of the world for 5,000 years -- including in the Sikh community in which her parents were married -- and our opposition to the idea says a great deal about the ways in which culture and history have shaped the way Americans think about personal choice.

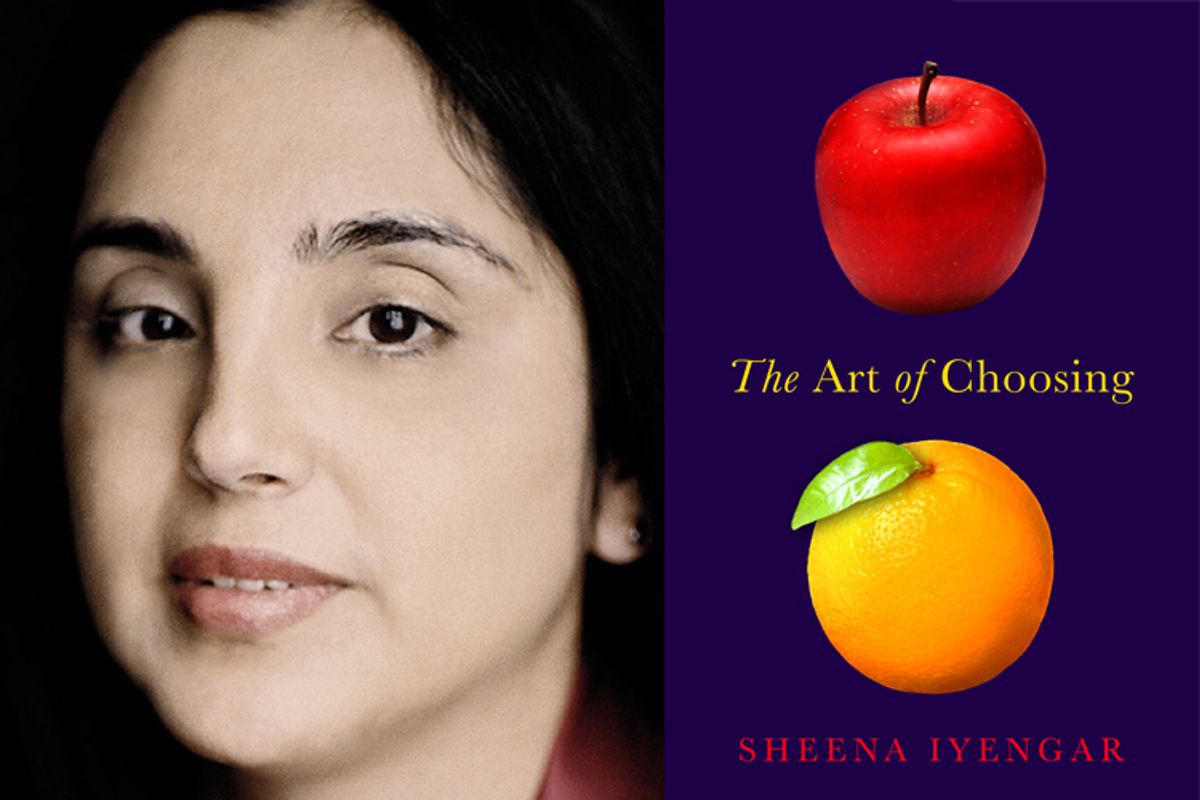

Iyengar, who grew up in Sikh enclaves in New York and New Jersey, is now a professor of business at Columbia University and one of the country's leading researchers on decision making. In "The Art of Choosing," a broad and fascinating survey of current research on the subject, Iyengar stitches together personal anecdotes, examples from popular culture, and scientific evidence to explain the complex calculus that goes into our everyday choices, from picking our favorite soda to choosing our medical insurance. She also writes about the ways in which her blindness -- Iyengar lost her sight as a teenager -- has given her a unique perspective on the subject.

Salon spoke to Iyengar over the phone about how ballot order cost Al Gore the 2000 election and how a blind researcher learns about color.

Why did you become so interested in researching the way people make choices?

When I was very young, my background as a Sikh-American made me aware of the tensions that underlie choice. Being a Sikh meant having to do what Mom and Dad said, and going to temple, and Mom and Dad choosing who I would marry. But going to an American school taught me that I was the one who’s supposed to make those choices. There was the constant tension between following my duties and giving in to my preferences. I was becoming aware of the fact that different cultures provide different scripts about choice.

What expectations people bring to choice is one of the dominant themes of my research, along with the idea that choice has its limitations: When I was going blind, questions were constantly being thrown at me. Will she be able to go to school by herself? How is she going to survive? What can she do and not do? It constantly reminded me that there are limits to what choice can offer.

In the book, you write that Americans are more attached to choice than people in many other countries. Why is that?

It’s a legacy we were given by the forefathers of this country. Thomas Jefferson and our other forefathers were influenced by the Greeks, the Romans and the Enlightenment period in terms of their ideas about political freedom, along with the Magna Carta, and the recently published "Wealth of Nations."

Political freedom and the free marketplace came together under one nation for the first time in history and then, to that you add the freedom of self-expression, which came about through the transcendental movement of Emerson. In this country, self-expression is primarily exercised through personal choice.

But this isn't the case in places like Japan, where, as you write in the book, children often prefer to follow directions rather than make their own choices.

The way we raise our children is very different, starting from the moment they’re infants. In America we tell our parents to bring their child home and put him or her in a crib; as they get older, children sleep in they own room not in Mom and Dad’s room. What are we training them for? It’s independence, because that’s what being empowered is all about. We give this script verbally and non-verbally.

When they’re learning to speak, we train them to answer questions like, "What kind of cereal do you want to eat?" By the time they’re 5 we ask them, "What do you want to be when you grow up?" We’re telling them that they need to learn to choose. Most children's first word in America isn’t "Mama" or "Papa" like in other countries, it’s "not." My son’s first word when he was two years old was "more."

By contrast, in Japan, you don’t sleep alone until maybe 8 or 9 or 10. You often take a bath with your mom until elementary school, and, as for asking a child what they want to be when they grow up, you wouldn’t think a child would be equipped to answer that question.

Can having too much choice be a bad thing?

There are times when the presence of more choices can make us choose things that are not good for us. For me the clearest example is that the more retirement fund options a person has, the less likely they are to save for their old age. It’s the same thing with Medicare and Part D [the federal program to subsidize medication costs], where the more options people had, the less likely they were to take advantage of the government’s offer. That’s where it becomes clear that this can actually be detrimental.

One significant cultural difference, with regard to choice, is the way people find their spouses. You looked at non-arranged and arranged marriages in the book, and came away surprisingly positive about the latter.

The model is so different that it makes it very tough to compare them. The arranged marriage will lead in theory to less quarrels because you know, for example, what religion you’re going raise your child in. In the case of a love marriage, love is supposed to conquer all, but what do you do when you have different opinions about how to feed your child or save money? What we can learn from the arranged marriage is the importance and value of compatibility. I think what the love marriage can teach is the importance of shared understanding.

When I first moved to the United States from Canada, one of the things that struck me about American medicine was the surprising amount of choice I was given to decide my own treatment. As you write in the book, this is a fairly recent development. Is this a good thing?

You need to give patients some feeling of control during the medical process. They at least have to feel they’re cared for and that their best interests are being accommodated and considered, but I think the file recommendation has to come from that doctor because when you’re sick it’s very difficult for a patient to truly figure out what is the best treatment. To have the person who doesn’t know anything about cancer make the decision about treatment raises a lot of potential problems.

I think that goes to the core of the current American healthcare debate. A lot of people are worried that with public healthcare, they’ll lose the ability to make those choices.

It’s a big part of it -- and it’s something that constantly separates the Republicans and Democrats: Are we going to create healthcare which provides equal outcomes for all, giving everybody the same helping hand, or are we going to provide equal opportunity for all, by removing both barriers and aid? Those are two entirely different scripts about what a fair choice is and we hold to them very passionately. We’re convinced the other side either doesn’t see the truth or is naive. When Obama says we have differences of opinion that run deep, this is the difference of opinion: what constitutes a fair choice or a fair distribution of choice.

We seem to be in an era where everybody is showing off their personal choices -- favorite movies, quotes, photos of themselves -- on Facebook. Are these self-defining choices more important than they used to be?

You should watch these videos on YouTube by this 17-year old Asian-Canadian girl named beautycakez. She shows you all the things she bought -- from Armani exchange, for example, or a maroon sweater from French connection -- and you can send her e-mails and ask her questions. Her identity is a compilation of her consumer choices. She’s trying to create an image based on her purchases. That’s what she wants you to know her by and she’s hoping that that's an expression of her identity. It’s a self-validating exercise, and it’s kind of boring to watch it, but people do.

I think we’re definitely more conspicuous about these kinds of choices. I think we believe they play a bigger role than they did before, but I’m not sure if they do. Either way, the link between the person we want to be and the choices we make are now more clearly linked in our mind.

At one point in the book, you write about the ways names shape color preference. How did your blindness affect your ability to research color?

Because I’m blind, I’m not emotionally invested in a particular color or color combination. I’m much more able to discern how invested sighted people are in what looks good and how enormously subjective it is. It was my struggle with color that made me pay so much attention to it. Names of shades of particular colors kept changing -- along with the idea of what color should go with what others.

Sighted people’s emotions are tied not just to what they’re seeing but what they’re feeling while they’re seeing. If you walk up to a sighted person and say that outfit just doesn’t go, or that their makeup is cakey, they'll say, "How can you be so cruel?" It's because you’re commenting on the person's judgment. Now imagine if you're blind, and you don’t have an emotional investment in that. If somebody tells me my makeup is caked, I'll go, "Oh, I'll fix it."

Is it really true that Al Gore would have won the 2000 election if his name had been first on the ballot?

Oh yeah. This is research done by John Krosnick at Stanford. It's estimated that Bush coming first on the ballot cost Gore 2 percent of the vote, which in that election was critical. Why do we vote for the first person? When you open up a menu in a restaurant the first dish serves as your reference point, when you interview people for a job the first person serves as a reference point; it’s just human nature.

Shares