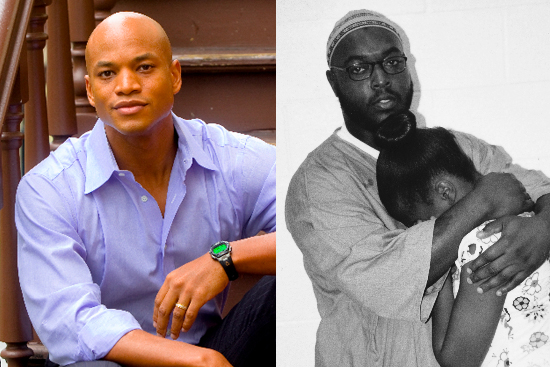

In late 2000, Wes Moore, an ex-military officer and soon-to-be Rhodes scholar, came across a series of articles in the Baltimore Sun that caught his attention. They chronicled the aftermath of a robbery gone awry: A few months earlier a group of armed men had broken into a Baltimore jewelry store, and in the process of making their escape, shot and killed an off-duty police officer named Bruce Prothero. It wasn’t just the violence of the act that shocked Moore, it was the name of one of the suspects: Wes Moore.

Several years later, when Moore (the Rhodes scholar) returned from his studies at Oxford, the story continued to haunt him. Here were two men with the same name, from the same city, even the same age, and two dramatically different trajectories. In the hopes of finding out why, Moore began writing and visiting the man (who had since been sentenced to life in prison). The result is “The Other Wes Moore,” Moore’s vivid and richly detailed new book about both men’s childhoods in Baltimore and the Bronx.

Both, as it turns out, grew up in single-parent households with working-class mothers, in neighborhoods rife with crime and drugs. But while one Wes Moore was saved from delinquency and falling grades by a transfer to a military school, the other Wes fathered several children, surrounded himself with addicts, and fell deeper and deeper into the drug trade before, eventually winding up behind bars. The book is also a call to action: It includes a glossary of vetted community organizations, and proceeds of the book will be donated to several nonprofits.

Salon spoke to Moore over the phone about the lessons of his book, the meaning of Barack Obama and the complicated blessings of the American military.

You came up with the idea for the book after seeing the articles about Wes Moore’s trial. Aside from your names, what do you both have in common?

When he was arrested he was only a few blocks from where I was living. We both grew up in single-parent homes with our mothers, since we didn’t have fathers in the household. Even when we were growing up in the different neighborhoods — Baltimore and the Bronx — the tenor of them was similar. We both got disillusioned by school at an early age, and had run-ins with the police.

And then you decided to contact him in prison …

It initially started as pure curiosity on my part. He was actually much more open than I thought. I was surprised he wrote back to my letter. He started by saying when you’re in prison you think nobody knows you exist anymore, and he just literally went point by point for every question.

Then I realized there might be a larger story to be told. There were two main factors that made me think I should write this book. One was that I thought about the police officer’s family, and the tremendous tragedy that happened to them. The second was something that Wes told me. He said, “Listen, I have wasted every opportunity that I’ve ever had and I’m going to die in here, so if you can do something to make a difference, you should do it.”

The most heartbreaking part of the book occurs when the other Wes Moore almost ends up leaving the drug trade, thanks to a job training program called Job Corps — but then he gets sucked back in. What went wrong?

What we saw in the case of Wes is actually typical and illustrative of the situation that you have with ex-cons. Many of these people are disillusioned with school. They don’t have college degrees. They have a record so they’re not legally eligible for a lot of jobs, and to that, you add the burden of children. They’re often not welcomed by their family or have precarious relations with them, and we’re asking them to become upstanding members of society.

That was one of the most heartbreaking interviews with Wes, when we met specifically to talk about that. After that I went to my car, and I was unable to drive for half an hour because I was trying to absorb how close he was to doing something with himself, and yet how far he was and didn’t even know. We need to figure out a better way to address recidivism in this country and find a better way to help those people who have served their debt to society, because we can’t continue to pay for this financially and morally — having people with rap sheets as long as their arm because in many cases they don’t know any other way.

Now that you’ve written the book, what lesson do we take from your stories? What made you succeed where he failed?

There is no one answer. We weren’t responsible for the neighborhoods we happened to be born in. There are lots of issues that affect these kinds of outcomes: the abilities of families to use leverage to change their situation, their ability to support a child, the ability to give children the sense that they belong to something bigger than themselves.

In the book, you credit the military for setting you on the right path. But a lot of people see the military as an institution that preys on men in disadvantaged situations.

Have there been problems with the military, historically? Absolutely! I can’t ignore them, but to say the military is an unfair institution that feeds by preying on people is, I think, unfair by any stretch of the imagination.

It’s something I had to wrestle with. I come from a community and a family that is very skeptical of the military, and, in some ways, has thought it hasn’t always lived up to its creed. I know the man I am has a lot to do with my military training, and the soldiers I went through combat with. It gave me the opportunity to pay for college, and some of my proudest moments have occurred while wearing the uniform.

And it’s worth remembering that the military has led the charge for a lot of social issues. Desegregation occurred in the military before it did in the rest of society. It has concepts of equal pay and equal worth for men and women, which society still doesn’t have.

As your book suggests, a lot of poor Americans aren’t getting the help they need from public institutions. Does that ever make you question your decision to fight for the country?

My grandparents grew up at a time when, if they were driving through the country, they would make sure they eat whenever they could because you never know when the next place will come that will allow black people in. Are there still real systemic problems? Absolutely! But I think about the level of progress that we’ve made, and the country that I’d like to see in the future.

Both you and the other Wes Moore make some bad decisions — at one point he tries to stab somebody — because you’re unwilling to lose face. Do you think the culture of machismo among many young black men is part of the problem?

I think there’s a larger problem in terms of understanding what manhood is. We have so many families in so many situations where people don’t have men in the home, so they don’t know what manhood really means. There are so many women across the country who have the extraordinary burden of raising their children on their own. My mom said, “I can try to teach you how to be a good human being, but I can never teach you how to be a man.”

We need to have a stronger system of support in order for that to change. Seeing so many kids feeling so alone and looking for acceptance, if we’re not willing to show these kids a larger sense of community, those guys in the gangs will. One of the great things about this book was creating ties with organizations across the country doing work with communities and kids that are largely forgotten about.

Another new memoir, Thomas Chatterton Williams’ “Losing My Cool,” argues that hip-hop has a toxic effect on the black community. Do you think that’s true?

When a lot of kids listen to music and look at movies, they can’t tell the difference between fact and fiction. But I think it’s as difficult to throw a blanket over hip-hop, as it is over any musical genre. I think it has a clear responsibility as far as the level of influence it has. I’ve listened to it since its inception. It was a burgeoning musical genre in the Bronx when I was growing up, and it has grown with me. It’s like other musical genres — some is fantastic, and some is not.

For many people reading the story of the other Wes Moore, the first reference they’ll likely think of is HBO’s “The Wire.” How do you think that show affected the city of Baltimore?

From a P.R. perspective I don’t know if it was the greatest thing for Baltimore, but it forced Baltimorians to have a conversation among ourselves about the city we want to be. It exposed parts of the city that even Baltimorians didn’t know much about. We often don’t understand what’s happening elsewhere in our own city, which is fascinating. I think a lot of cities have this split personality, but Baltimore really is a tale of two cities. A lot of folks in East Baltimore don’t know West Baltimore.

There was a recent NPR piece arguing that your book represents a new way of looking at the black American family. Do you think that’s true?

There’s this whole idea of talking about the black family, and thinking, “This is who the black family is.” But it’s extraordinarily complicated. It’s like saying, here’s the Latino family. I think the book helps show the complexity of the black family — the fact we have families that are mixed immigrants, different family members enmeshed in different problems and trying to break free. Sometimes broad strokes do more harm than good.

Do you think it would have made a big difference in your life if a black president had been elected during your childhood?

I think it’s fantastic we have a President Obama. But if that kid in West Baltimore or in the Mississippi Delta can’t see him or herself in that position — if it can’t be real to them — it’s not going to mean a whole lot. It’s not just about putting more faces in positions of power, it’s about helping that power translate to those kids. When people became involved in my life, and taught me to dream and think I could do X, Y and Z as long as I was willing to work for it, that happened regardless of who was in the office. That was something I needed to do personally.

Do you think the other Wes is resentful that he ended up in jail, and you’re writing this book?

I don’t think he ended up resentful. He’s had a chance to read the book, and he had two reactions: He was amazed I got all the facts right, and amazed at how little he’s done with his life. I don’t know if he’s resentful, but I think he’s, in some ways, hurt that he’s not been able to do more. But he also understands that he’s made some very unforgivable decisions and now he’s going to have the rest of his life to ponder them.