In November of 2007, Jeff Deck encountered a sign that would change his life. He had just returned from his five-year college reunion at Dartmouth College, embarrassed by his lack of accomplishment in life, when, walking near his apartment in Somerville, Mass., he encountered a sign that had already stopped him in his tracks multiple times: "Private Property: No Tresspassing." The extra "s" in the sign had, as he puts it, long been "a needle of irritation" -- but now something had changed: He felt the urgent need to correct it.

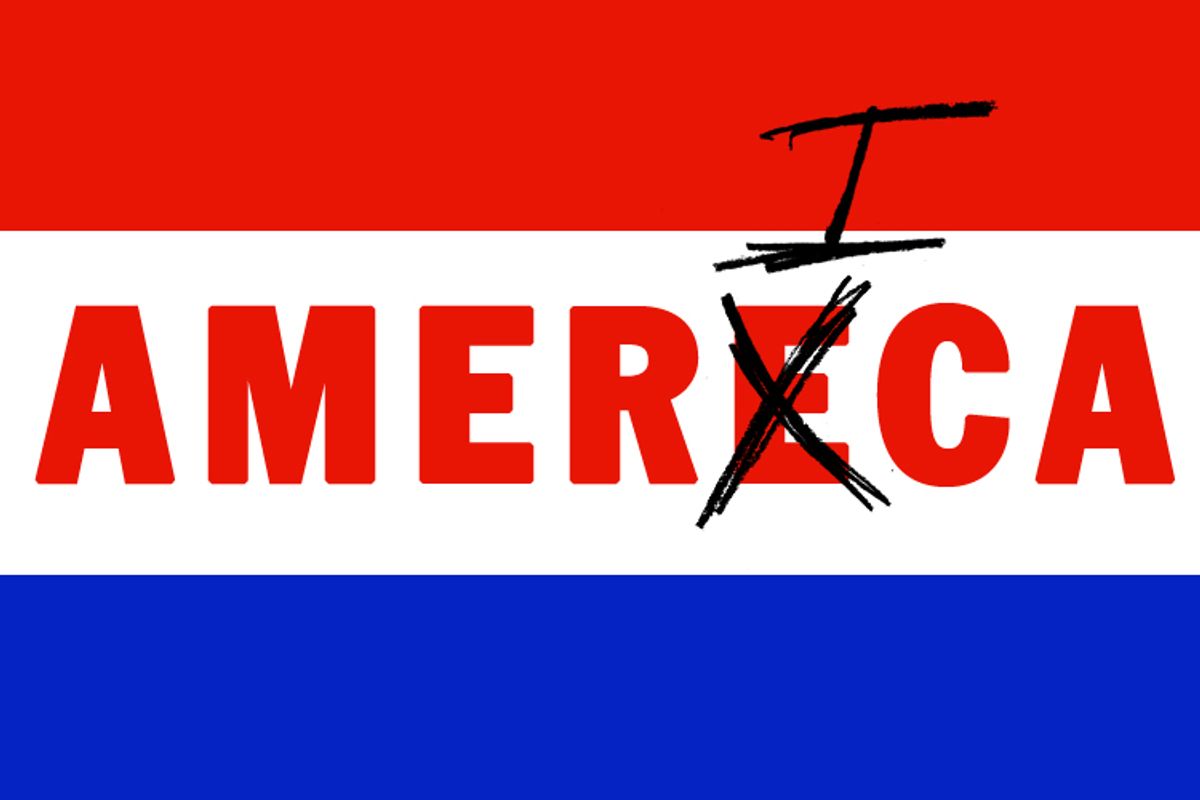

In the days that followed, Deck decided to give his life some purpose (at least for a few months) and, several months later, set off on a road trip around the United States in order to document our country's many misspellings. He gave himself the mandate of correcting at least one spelling mistake every single day. Together with a rotating cast of friends, he traveled from the Northeast ("bread puding") to Georgia ("pregnacy test") to Wisconsin ("Milwuake Furniture") while documenting each mistake and each correction on his blog -- a mission that taught him about the breadth of America's language problem and its citizens' strongly divergent attitudes toward the English language.

Deck's new book (co-written with Benjamin D. Herson), "The Great Typo Hunt," is a breezy and fun (if occasionally repetitive) catalog of his journey. It's most interesting when it delves into issues of class and race -- subjects that inevitably come up, given that Deck and Henson, both university graduates, spend time correcting spelling in the Deep South -- and in its discussion of the plasticity of the English language.

Salon spoke to Deck over the phone about the Internet's effect on language, the socioeconomics of spelling and why our children aren't writing as well as they used to.

Why are typos such a big deal to you? Why should we bother to correct them?

Typos cloud communication, which is the primary purpose of writing. If your text has typos, it’s going to take your readers longer to read it. If typos get in the way of your text, it’s going to cause a problem, especially today, where you often only have a second to grab your reader’s attention. It can also be a warning sign that whatever text you’re looking at was created by someone who might not be paying that much attention. Punctuation was invented shortly after the printing press specifically to stand in for speech effects and improve the whole flow of writing and make things easier for the reader.

Do you think America's typo problem is getting worse?

Over the past several decades, there’s been a definite move away from phonics-based education in spelling and grammar -- which ties the sight and sound of words very closely together -- toward what's sometimes called the "whole word method," which is based more on the sight of words. With phonics you learn to sound out the parts of each word and then put them together, instead of the guesswork that's involved in the "whole word" approach.

There was an interesting book that my co-author Benjamin discovered as we were on our typo hunt, called "Why Johnny Can’t Read," from around 1955. The author talked about some of the most common types of errors out there, like double-letter confusion: "timming" instead of "timing," and "shiping" instead of "shipping." It had this whole list of common typos, and a lot of them were the same ones we saw on this trip.

It can seem pretty condescending to be correcting typos, in particular when a lot of the people responsible for them are probably immigrants still learning English.

I think the capacity for cruelty is just too much when you’re going after people writing in English as their second language -- my French would be lucky if it were at that level of semi-comprehensibility -- so we tried to stay away from those. But even with that aside, socioeconomics are definitely a factor to consider and we had to be sensitive to that.

Especially given that you're two white guys with university education.

Definitely. But we would get defensive reactions from people in some very unexpected places. For example, when we were doing some typo hunting at this tulip festival in Albany, we found a typo in a sign in one booth which talked about an "internationally renown" artist instead of "renowned," and when we pointed out this mistake to the person running the booth, he said: "I know that this is right. What college do you teach at?"

Why do you think so many people are so defensive about correcting their language?

Language can be a very personal thing. Even if it’s just a sign you wrote up about a sale on watches, it’s still something you’re putting out that you wrote. So if someone comes along and says, "This is spelled wrong," the automatic reaction is, "They’re criticizing my writing, they’re criticizing me." I think it’s understandable, but not necessarily the most productive reaction.

The most loaded topic surrounding language in this country right now is the movement to make English the "official language." Where do you stand on that?

It's kind of silly to officially proclaim English the national language when English is itself a product of many different influences. American English in particular has been wonderfully adaptive and welcoming of fun new words and constructions, and I just think it’s a mistake to try and make language a matter of law and punishment.

Right. This isn't French Canada. It’s not like the English language is going to die out because no one's speaking it.

English is the global language of business right now. It's not in any danger of going away or being snuffed out.

Spelling mistakes are a big part of the way the English language has evolved -- and been so successful on the global stage. Aren't you also holding back language?

We came under criticism from people at two different ends of the language philosophy spectrum. In our book we refer to it as the hawk versus hippie dilemma. You have grammar hawks who are ready to jump on anything that has the risk of being non-standard and call it a mistake, and, on the other hand, you have descriptivists who basically have a free-for-all approach. At its most extreme, descriptivism argues that most of these typos aren't mistakes, it's language change in motion. We tried to strike a middle ground and say, OK, we’re going to recognize that English is a constantly evolving organism and that the spellings of some things are going to change over time. I’m not going to go around to every instance of the word "donut" and add in the "ugh."

On the other hand, if you look at certain errors on an individual level, where someone accidentally throws a "V" into the word "entertainment," like we saw on one sign in Atlanta, or a sign we saw in Vegas that offered "horsebacking riding" instead of "horseback riding," these are not pieces of evidence of some growing consensus; these are just individual errors. They're something that I think you can in pretty good faith go after.

What's the favorite typo that you've corrected?

We were in San Francisco, and we came across this exhibit at the Cartoon Art Museum in which every caption had at least one typo and sometimes multiple typos. It really wasn't flattering to the people whose work they were trying to display. We brought the typos in the exhibit to the people who were working there, who were kind of dismissive and tried to pass on the blame. So I put out a call on the blog encouraging people to make some polite requests to the management at the Cartoon Art Museum to change their signs, and a couple days later we heard from the curator, who wasn’t too happy but told us that the signs had been fixed. That was a good team effort.

The Internet seems to be speeding up the way that language is changing, partially because it seems to be throwing up neologisms every five minutes, like "Fail."

It’s certainly been a much quicker way to introduce new slang words and meanings into the language. The flip side to that is that it can spread around common mistakes – "its" versus "it's." I think the important thing is to not just jump on every new fad or slang word that comes along, to wait a few years and see if people are still using the word or construction.

Do you think the Internet is decreasing our interest in proper grammar and spelling? Both you and I have worked as copy editors, but now many magazines and online publications have cut their copy-editing staff, partly because of the way the Internet has changed the industry.

I’ve watched copy editors become an endangered species in the marketplace over the past couple years. Copy editors are not valuable just for catching things like typos but also for factual errors and suggesting ways to tighten text. It’s not the Internet that's devaluing our appreciation for good spelling and grammar so much as the immediacy that the Internet feeds and bolsters. It would be nice if everyone could somehow find a way to slow down and say, OK, I can wait five more minutes for a news update and that's not going to decrease my quality of life.

The French have a body called the Académie Française whose mandate is to preserve the French language and mediate changes. Should the same thing exist for the English language?

I think it is possible to get a little too academic about standards when you’re not taking into consideration people's on-the-ground use of language. They considered a formal American academy of English language standardization shortly after the Republic came together, and people just didn't want that. It felt a little too much like state control, the kind of thing they'd broken away from Britain to escape.

Shares