Near the climax of the first episode of the new miniseries "Sherlock," constables from New Scotland Yard are industriously tearing apart the eponymous hero's Baker Street flat. Inspector Lestrade's team has come to believe that the arrogant consulting detective is not only holding out on them in a serial murder case, but is the likeliest suspect himself. Harsh words are exchanged and one officer tosses out an epithet: "Psychopath!" Benedict Cumberbatch, whose lethal glee in the role of Holmes can barely be contained, snaps, "I'm a high-functioning sociopath. Do your research."

The notion that Sherlock Holmes' talents betray a diagnosable pathology is a familiar theme; Nicholas Meyer famously put Holmes on Freud's couch for "The Seven-Percent Solution." In two new versions of Arthur Conan Doyle's ever-reborn hero, we can spy our current fascination with the figure of the brilliant but socially maladjusted savant, just a symptom or two shy of a DSM-specified disorder.

The notion that Sherlock Holmes' talents betray a diagnosable pathology is a familiar theme; Nicholas Meyer famously put Holmes on Freud's couch for "The Seven-Percent Solution." In two new versions of Arthur Conan Doyle's ever-reborn hero, we can spy our current fascination with the figure of the brilliant but socially maladjusted savant, just a symptom or two shy of a DSM-specified disorder.

"Sherlock," in which Cumberbatch stars, is a loving if heavily reengineered adaptation of the well-known adventures of Holmes and Watson, which time-shifts its central pair a hundred years forward without so much as a backward glance at Victorian frippery, steampunked or otherwise. Instead, Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat's creation for the BBC and "Masterpiece Mystery!" remixes Conan Doyle's detective stories for the era of GPS smart phones and CSI-style forensic labs. The tone is one of darkly deadpan comedy: A good many of the classic exchanges between the swift-thinking detective and his clay-footed friend John Watson (still a war-veteran doctor) are recast to milk laughs out of Martin Freeman's mingled wonder and rue over his fate as a sidekick to a pale-skinned Byronic scarecrow who sports manners only slightly more acceptable than those of Hugh Laurie's Dr. Gregory House.

The slick production hurtles viewers through a London landscape composed of surfaces both glossy and gritty, with a showy velocity that nevertheless mimics the stories' addictive power. And this Sherlock has all of the digital age's playthings at hand to take the place of his namesake's library. Gatiss and Moffat thankfully aren't restricting themselves to the diet of dully damaged serial killers that crime drama seems to feed on these days. In "The Blind Banker," an international smuggling ring plays a charmingly old-fashioned role, providing the sense of exotic menace that characterized Holmes tales like "The Sign of Four." While Watson blogs Sherlock's adventures, the prosaic ubiquity of the Internet itself barely registers. The adventure is exuberantly physical, with lots of leaping from balconies and rooftops, kidnappings and gunplay. I suspect a real-world Sherlock would find a way to solve these crimes without stirring from his recliner. But he'd make lousy television.

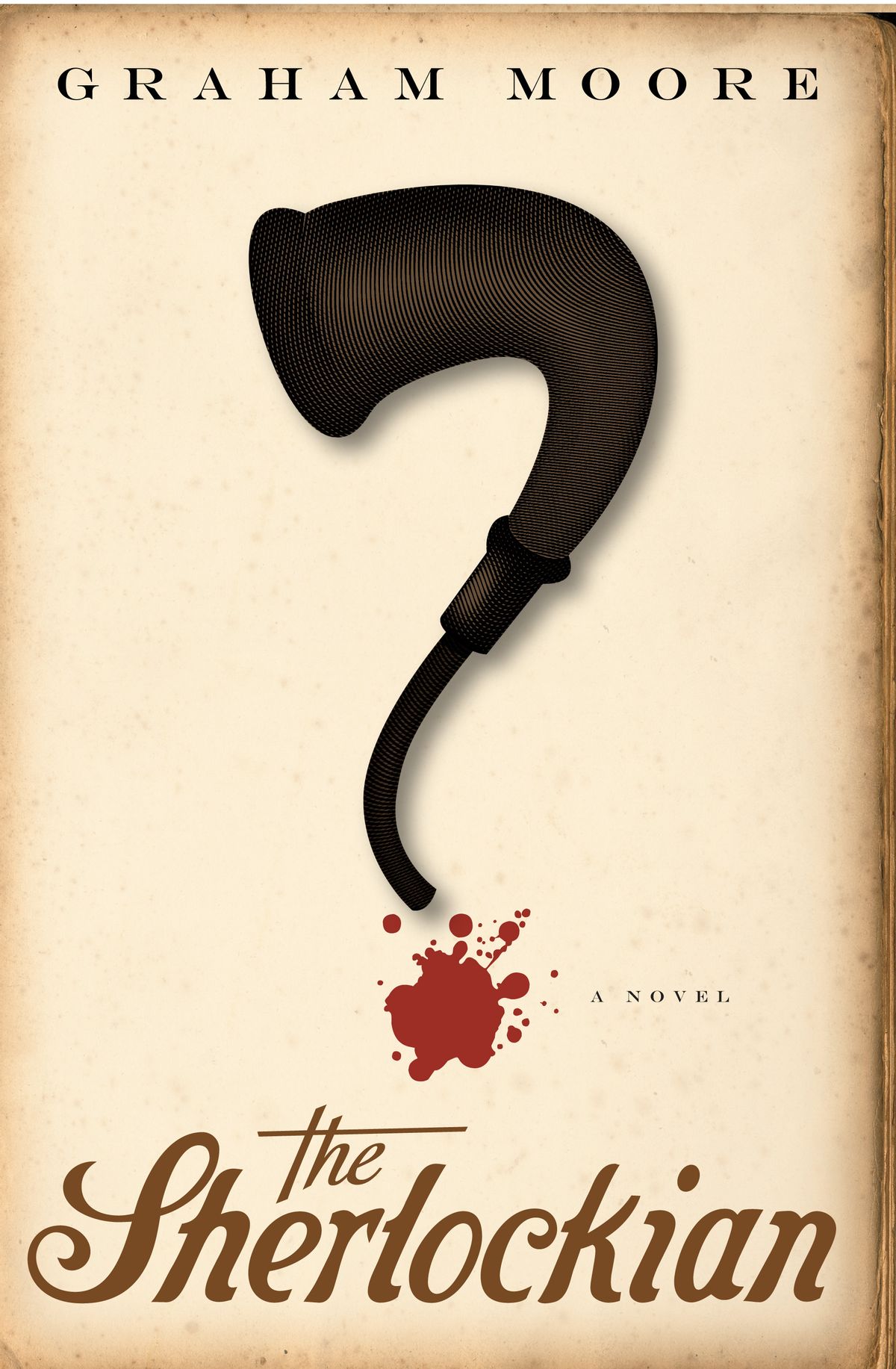

Graham Moore's mystery "The Sherlockian" is by contrast a quiet affair, generating a surprisingly melancholy mood. The novel approaches its great original obliquely -- Holmes is frequently evoked, but resolutely absent. His stand-in, however, offers noteworthy parallels with Cumberbatch's Sherlock: Harold White is, if not a high-functioning sociopath, then certainly easily locatable on the spectrum of social dysfunction that runs from "charmingly geeky" to "functions best at fan conventions." At 29, Harold is marked not only by his speed-reading talents, but also by his "astigmatism [and] sweaty, shivering hands." What's most notable about him, however, is his obsession with all things Holmes, down to the deerstalker hat that he wears sheepishly, not unlike an aging Trekkie who can't quite give up a pair of Spock ears.

Newly inducted into the Baker Street Irregulars, an invitation-only society of Sherlockian scholar-enthusiasts (based on a real group who commune by trading obscure Holmes quotes and quaffing Scotch), Harold finds himself moved to investigate when a prominent member, who had claimed to have found a lost Conan Doyle diary, turns up dead in his hotel room. The word "elementary" is scrawled in blood on the baseboard as an apparent taunt, the diary is nowhere to be found, and Harold takes on the dual quest for murderer and missing journal, in company with a more socially adept and personally alluring reporter named Sarah, who is willing to play Watson if it'll get her, she says, her story.

Alternate chapters, meanwhile, give us a parallel mystery starring Arthur Conan Doyle himself, in the days after the writer had first tried to dispose of his overbearingly popular (for the author, at least) hero in the story "The Final Problem," only to discover that the Holmes-adoring public regarded him as some kind of murderer, or at any rate a supreme killjoy. Matters get out of hand when a letter bomb is sent to Conan Doyle at home. The police won't treat the case seriously, and so Conan Doyle -- in company with theatrical manager Bram Stoker, the future author of "Dracula" -- sets out to find the bomber. In so doing, though, he stumbles onto a crime of far greater moment, and soon he's following a serial killer's trail (Conan Doyle really did get brought in to help solve crimes, though this one is a fiction). Hampered though he is by the fact that as a respectable physician and author he has few of Holmes' skills, he becomes devoted enough to the chase to shave his mustache and put on a dress.

Throughout both cases, Graham plants effective red herrings and false trails, and the two stories inevitably intersect, with the final scenes of one providing rationale for the other at a suitably resonant locale. The conclusion clears up the mysteries tidily and offers Harold a vision of life without the deerstalker hat, but there's little here to raise a shiver. The literary red herring Conan Doyle himself offered in the Sherlockian canon was that Holmes' intellectual triumphs were what readers should admire, yet all the while the real seduction was the atmosphere of romance: a hansom rattling through the fog, or strange beasts creeping around the precincts of some twisted squire's secluded manor. Harold himself pines for the gaslit nightworld through which his hero prowled.

Gothic chills, fortunately, can be accessed in any era. I'm cheering for Cumberbatch and Freeman's return, and their excursions onto, let's say, a moonlit moor -- roamed, perhaps, by a genetically modified hound?

Shares