Over the past few years, the New York Times bestsellers list has been flooded with a new kind of confessional memoir: the comedian's tell-all. Whether they're lamenting their sexual misadventures (Chelsea Handler), doling out advice for a Friar's Club-style roast (Jeffrey Ross) or riffing on the horrors of adolescence (Patton Oswalt, Sarah Silverman), stand-up comics have proven themselves to be an endless source of fascination to the reading public as well as a bankable commodity for book publishers. And while its origins may be rooted in celebrity publishing, this trend is no longer confined to the lofty heights of talk show hosts and A-List personalities.

The latest offering comes from veteran sketch comedian Michael Showalter, the star of the MTV series "The State" as well as co-writer of the cult classic, summer camp flick "Wet Hot American Summer." In 2009, he appeared alongside Michael Ian Black in Comedy Central's "Michael & Michael Have Issues," a show within a show whose "meta" conceit charmed critics but left audiences scratching their heads. Perhaps it's only fitting that his memoir, "Mr. Funny Pants," is a sometimes poignant, occasionally tedious and often hilarious account of one comedian's struggle to write a comedic memoir.

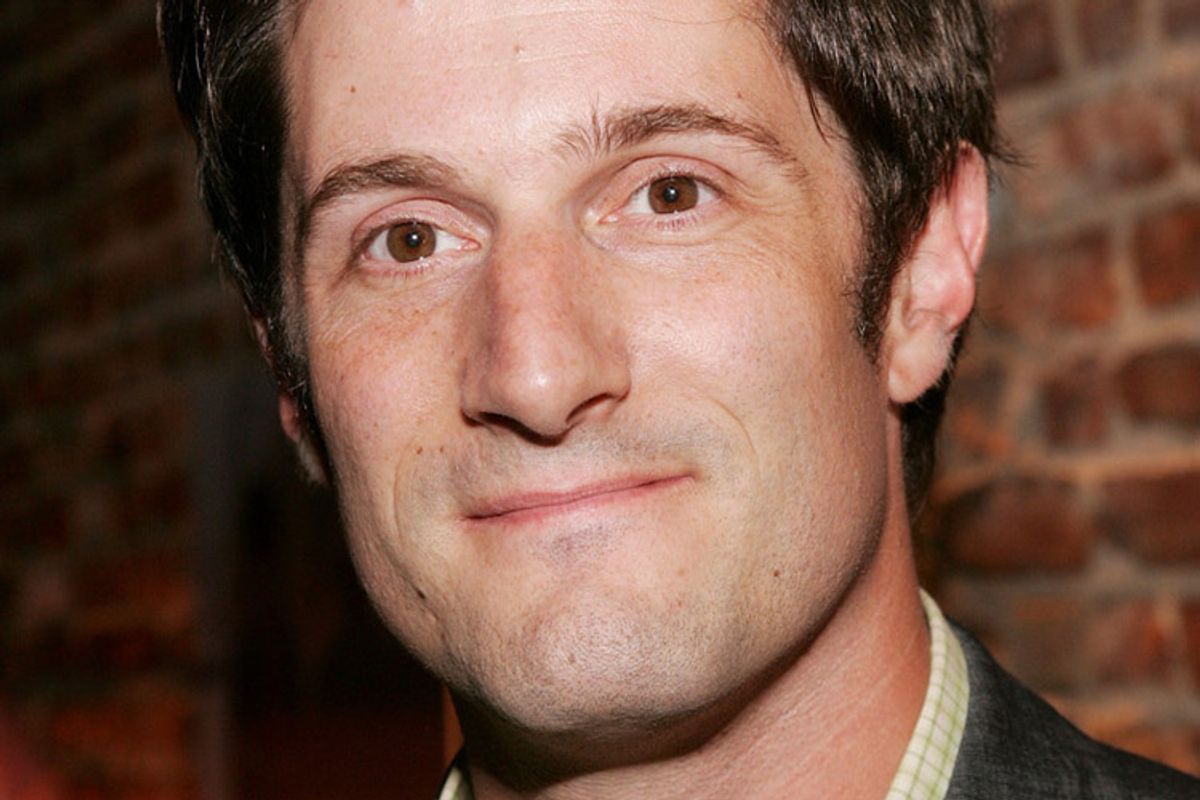

Salon spoke with Showalter over the phone about the literary appeal of stand-up comics as well as the death of the sitcom, embarrassing head shots and the endless pretension of the sun-dried tomato.

"Mr. Funny Pants" is a memoir about the process of writing a memoir. In certain sections, you even try to anticipate the critical reception for a book you haven't yet written. Did you ever find yourself getting tangled up in all these layers of meta-narrative?

Before I even started, I had this idea in my head that real authors have a whole process for writing a book. They wake up in the morning, eat their oatmeal, pace around a room for a little while and then work for several hours at a time. That's not me. I'd never done anything like this before, so I thought it could be a funny angle to write about not having a process.

Did you try out any of your chapters in your stand-up routines?

I didn't perform any of it in front of an audience, which is one of the more interesting and terrifying things about writing a book. You really have no idea whether or not what you're writing is funny. In stand-up and sketch comedy, you know right away and you can make your changes accordingly.

In a chapter titled "About Brooklyn," you describe Williamsburg as a Disneyland populated by girls with bangs and bearded young men in uncomfortable shoes. You spend a decent portion of the book poking fun at hipsters and yet you've always been something of a hipster hero. How do you make sense of that?

I've always balked at anything that feels like a clique, even if it's not always in my best interest to do so. I like each individual, fedora-wearing hipster -- it's just the greater gestalt that rubs me the wrong way. I find it a little oppressive how much uniformity there is in their attempt to be countercultural. At the same time, I recognize that there's a quirkiness to my shows that really resonates with that audience. Without hipsters, I'd probably be working at Starbucks.

Your memoir betrays a certain fatigue with Hollywood. Is that a product of your individual experiences, a reaction to the state of mainstream comedy today or some combination of the two?

It's my individual experience more than anything. I didn't discuss this in the book, but I grew very disillusioned about the moviemaking process after the release of "Wet Hot American Summer." After the movie premiered at Sundance, David Wain and I went to Hollywood to meet with producers and executives from some of the bigger studios. The prevailing attitude with everyone we met was: "We love your crazy sensibility, now do you think you could make a cookie cutter comedy?" Fairly or unfairly, I guess we had a kind of Wes Anderson fantasy that we'd be given carte blanche to make our next movie just the way we wanted.

Who do you think is doing great comedy these days, in or out of Hollywood?

Will Ferrell, to me, is the archetype of the great, Hollywood comedian. I like him now, but I know that if I saw him in high school, I'd idolize him like I do Bill Murray. He and his collaborators are doing what I think is great, mainstream stuff. Outside of the system, I think Tim & Eric [of "Tim & Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!"] do really interesting work. I'd throw Jim Gaffigan into that group as well. As far as modern-day sitcoms go, there's nothing out there right now that really calls me.

Why do you think that is?

Until I graduated from college, I never missed an episode of David Letterman and I'd watch sitcoms compulsively. At this stage of my life, I'm not nearly as big a consumer of comedy as I was when I was younger. Once I made it my profession, my enjoyment of it changed because it no longer provided a form of escape. Suddenly, I began to see the infrastructure behind each joke and set piece and the illusion was lost. But I do feel like comedies were different when I was a kid. They felt less market-tested and focus-grouped within an inch of their lives. The British version of "The Office" was one of the few shows to bring me back to a childlike state of wonderment.

What is unique about your brand of comedy?

My stuff seems to anger a lot of people. I've always found it a little puzzling, because I don't think I'm doing anything controversial enough to illicit that kind of response. A lot of my humor centers on the act of telling jokes and I think this can prevent certain audiences from suspending their feeling of disbelief. It might piss a few people off, but I can't help it. I've always been more interested in an album's liner notes than the actual recording. At some point, though, I'd like to get past this obsession because I don't just want to be the "meta" guy for the rest of my life.

Why do you think so many comedians are writing memoirs these days? Does stand-up translate especially well to long-form nonfiction?

Given the current state of publishing, I think it helps to have a brand name on the cover of your book. Comedians are proven commodities with built-in audiences. They may not have the writing chops of a Dave Eggers, but they're salacious and funny and self-reflective. Their memoirs are also a lot easier to read than a book like "Oh the Glory of It All," which is several thousand pages long. I also think there's a little bit of follow-the-reader going on with Chelsea Handler. She's this monster bestseller and many comedians say: "Why not me?" I don't think many of us realize how hard it is to actually write a book.

In your memoir, you cite Judy Blume as one of your largest literary influences.

For me, Judy Blume is synonymous with adolescence. She was writing "tweener" novels before that was even a word.

And you actually read those novels? You're not putting us on?

No way! All of her stories felt very true to the kind of life I was living. Well, maybe not "Blubber," but that's the exception that proves the rule. She does as good a job as anyone of capturing what it's like to be a child growing up in the 1970s.

In a chapter called "Close-up Photographs of Your Face," you meticulously deconstruct your first head shot. It has to be seen to be fully appreciated. What is it about these photos that makes them so corny and tragic?

What other people see is the head shot. What you see is who you were when the head shot was taken -- the naiveté and the ridiculous bravado. At the time, I thought I was going to be the next James Spader. Then I had my heart broken 30,000,000 times. When I look at that picture, I see a newborn fawn covered in goo.

There's a nice chapter in your book about the secret to a great sandwich and all the ingredients that go into making one. It almost works as a metaphor for your writing process. My question is: What do you have against sun-dried tomatoes? Why do they infuriate you so?

Sun-dried tomatoes sound as though they'll make your deli sandwich instantly classier. What's never been documented is that they don't actually have any taste. They're chewy, flavorless impediments to your eating experience. I've talked about this onstage a number of times and no one has ever told me I'm wrong about sun-dried tomatoes. Ultimately, they're just a big dumb trend. Like fedoras and bangs and uncomfortable shoes.

Shares