Back in December of last year, television viewers watched CNN in disbelief as John Walker Lindh was seen squirming on a cot in Afghanistan claiming to be an American member of the Taliban. It was one of those moments when the madness -- not to mention the weirdness -- of war gets fully depicted on a single human face.

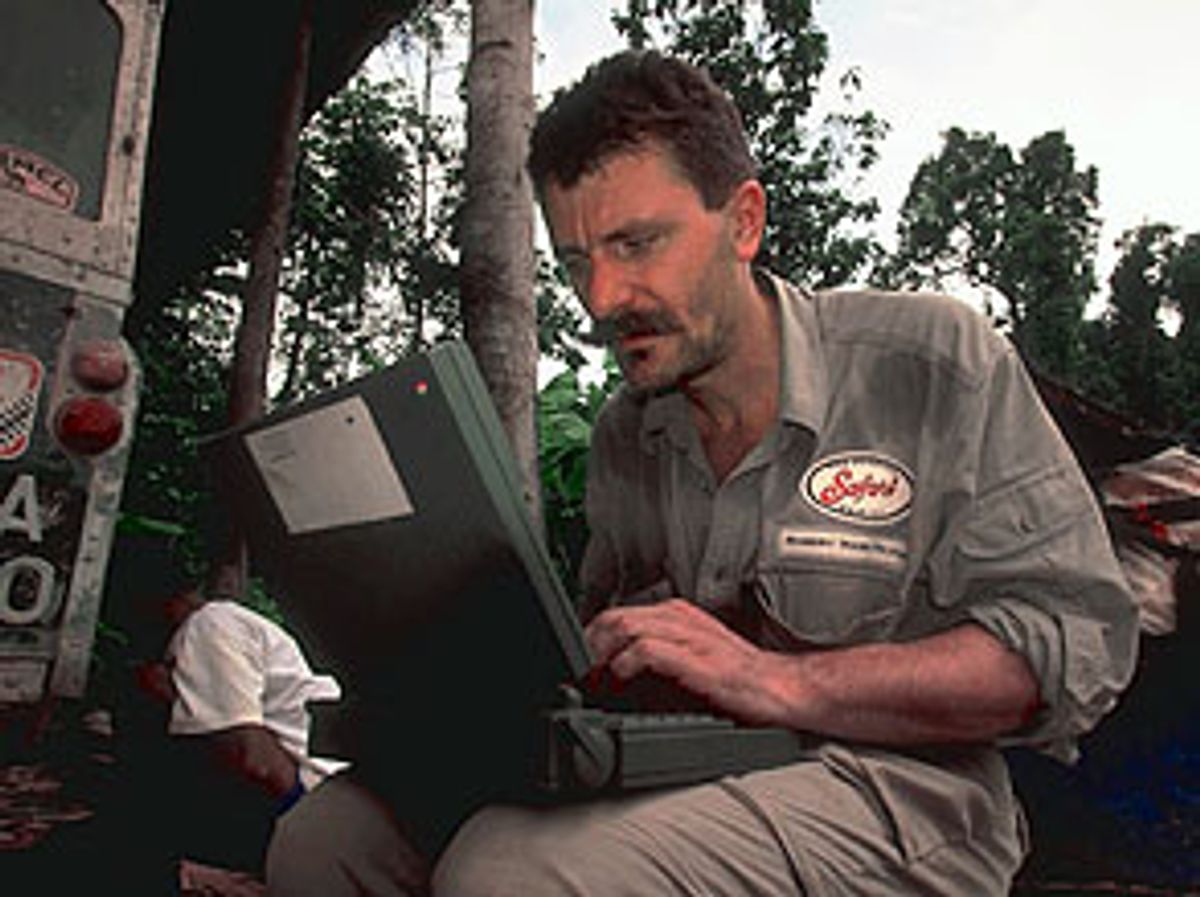

The person interviewing Walker Lindh was Robert Young Pelton, a sort of anti-travel writer who, over the course of several books and magazine articles, has demonstrated a strong affinity for war zones and rebel causes. For Pelton, this coup of an interview was another interesting case of being in the right place at the right time. In addition to talking with Walker Lindh in the aftermath of the Qala Jangi fortress uprising, Pelton had, "through intermediaries," arranged to spend time with legendary Northern Alliance general Abdul Rashid Dostum just as U.S. activities in Afghanistan were gaining momentum.

Dostum and his troops were working in conjunction with a Green Beret unit to liberate Mazar-e-Sharif when Pelton arrived on the scene. His story of that endeavor ran in National Geographic Adventure magazine and provided a firsthand glimpse of the war and the soldiers fighting it. In fact, Pelton had the kind of access that seems to have eluded many other reporters covering the conflict; his up-close and personal portrayal of a Special Forces unit in both moments of reflection and acts of bravery harks back to the days when journalists were actually among the fighting troops, not relegated to the briefing room at base camp.

Accessibility continues to be a bone of contention between the press and the Pentagon. Meanwhile, Pelton thinks the real story of the war is either being told too late, after the public has moved on to other topics, or is never even properly explored by mainstream media outlets that allow foreign governments to promulgate a more Western-friendly side of the story.

Pelton's blunt appraisals find their way into his travel books too; they focus on skulls and crossbones rather than sandy beaches. He's the author of "The World's Most Dangerous Places," a compendium of key information about how to get into -- and, more important, how to get out of -- various war zones, drug dens and atrocity-ridden enclaves the world over. The book is devoted to far-flung disaster areas like Sierra Leone and Somalia. Not surprisingly, Afghanistan gets a chapter. Pelton has been going there since 1995 to cover both the Taliban regime and the late Northern Alliance leader Ahmed Shah Massoud's efforts to topple it.

Pelton was getting ready to head back to Afghanistan to work on a documentary about the fortress uprising in Mazar-e Sharif when this interview was conducted.

Regarding your piece in National Geographic, you seemed to have access that members of the mainstream press didn't have, and I'm wondering how you went about achieving that.

Well, I'm not a journalist first of all, so that's probably why I have better access. There were about 200 journalists that had been waiting for six weeks in Termiz and Tashkent when I went over. I was quite intrigued by the activities in Mazar-e Sharif because I knew that most of the journalists had gone to the Panjshir Valley, which was a popular way to get into Afghanistan. But there wasn't much going on there. So there were about 2,000 journalists, according to my friends, sitting in the Panjshir area north of Kabul twiddling their thumbs, and I knew there was something going on in the north.

Just based on people that you talked with? Or just an inkling?

There were some preliminary news reports out of Iran and the Afghan press, plus I knew that Dostum had gone back in April so I was just intrigued why I wasn't hearing anything from there. And so I started calling [Western Afghan warlord] Ismael Khan's friends and Dostum's friends in the States and then once I set my trip up I actually called the president of CNN news and then I also called National Geographic and asked if they'd be interested in anything.

It felt like nobody was really covering the war; they were all talking about what they had for breakfast and what it's like to hear a bullet fly by and all this kind of crap. But nobody was really involved in the actual war. And obviously it was ongoing. So surprisingly, they both said yes. So I brought in a cameraman and myself and my assistant, and it took me four hours to cross the Friendship Bridge [leading from Uzbekistan into Afghanistan], and it was fairly easy to cross, even though the actual bridge was closed. The day I got there was the day of the fortress uprising. There were some journalists that came across on a day trip and they just stayed, which pissed off the Uzbeks something fierce.

That's the thing. You hear a lot about the press talking about how they have such limited access, but the military actually says that they can go wherever they want to go.

Well you'll hear this from the military. Every time you ask the military, "OK, I want to be put on a plane and I want to go to the front lines and I need to be back by 5 o'clock," they just laugh, because it's not their responsibility to chauffeur people around and to entertain them and feed them and protect them. But it's also a different country -- it's Afghanistan -- so if you want to go to the front lines in Afghanistan you have to talk to Afghans, and nobody seemed to talk to Afghans. I talked to Afghans. If I want to go into a country, whether it's Algeria or the Philippines or whatever, I don't ask the government's permission.

Why do you think that's the modus operandi for a lot of the press people over there?

Because they come from nice polite Western countries and they think that you need to ask permission. And some of them work for large corporations and they're technically not allowed to sneak into countries because they have insurance problems and legal problems.

So when you said you weren't a journalist, you consider yourself just a ...

I'm a writer.

You spent time with the Green Berets. You write that when you came across them they knew who you were from reading your books -- but what was the situation with the Special Ops commanders who may not have been on the ground with them. Did they know you were there? And didn't they care?

No, no. These guys had been through two months of a fairly profound experience fighting a war, and they sort of knew that if the story didn't get out from their lips, it wasn't going to get out at all. And obviously the senior commanders and also the Pentagon were going to rewrite the story and make it all pretty and perfect, and after the war they brought some journalists in to sit around and do stroke stories on the brave Green Berets or whatever. But the guys who were in the middle of it don't want to talk to anyone except guys like me because they just don't feel like the press gives them any respect. They don't let them tell their story.

It's the exact same thing with John Walker. I'm not there to judge these guys or to shape what they say into something that I can sell. I personally want to know what it was like to fight a war. And I think the reaction to my article was that the Green Berets got into a lot of trouble for talking to me and the public learned a lot about what it was like to fight a war, that it wasn't all perfect. These are human beings, they make mistakes and things happen that we're maybe not proud about or that we wish didn't happen but ultimately, all in all, it was a good war.

So the Green Berets did get in trouble?

Yeah. See, the military doesn't want information out. They only want the nice clean shiny stuff. And it's got to be processed and polished and the ugly bits removed.

So on that note, what do you think is going unreported over there?

Well, they kill a lot of people. The thing that doesn't come through is that we have killed thousands and thousands and thousands of people and you've very rarely seen an American soldier kill a foreign national [on television]. You've never seen a foreign national kill an American soldier. They're removing the bits that make war what it is and everybody's a hero. You drop a bomb on yourself you get a medal. That's the way the war has been fought.

From your perspective did you get a sense for whether or not military strategy was being influenced at all by the massive amounts of press people that were running around there?

Well, the military hates the media. The conundrum is that we live and die for the Constitution and one of the elements of the Constitution is freedom of the press -- the right of the democratic public to make decisions based on a free flow of information, without censorship, without people rewriting history. And basically since the Vietnam War, the military realizes that the press is the enemy, because the press is actually faster and more intelligent than the military is. They can assess a military situation long before the military figures it out.

I mean, John Walker is an example. John Walker is in custody because I found him, not because our military found him. I handed him over to the military so he wouldn't be damaged, but the bottom line is that the American intelligence resources on the ground are infinitesimal compared to the amount of media stuff, the amount of people running around gathering information. I mean, look at the crap that the Wall Street Journal dug up and all the New York Times information. The military doesn't have a clue. I mean there's more evidence in the John Walker case in the public archives than there is in the military interrogations.

Is that just a case of massive bureaucratic inertia?

The military controls information. They don't disseminate it. The press uses the highest-tech means to gather the information. They spend a cumulative millions and millions of dollars gathering information and then disseminating it around the world using electronic technology, and the military does exactly the opposite: They overly train people who are sort of culturally isolated and they gather information and they send it to a central point and then it's processed and edited and then disseminated very carefully to very selected people.

Some examples: I interviewed the top Taliban leadership when I was there. And the Green Berets were blown away: They're like, "Holy shit, you just talked to these guys? You got pictures of them?" And I'm like, "Yeah, you can get them off my Web site." The point is that the military is trying to compress information and withhold it, and the journalists are out there trying to find it and disseminate it, and I think what you can see from the article [in National Geographic] is there's nothing wrong with what we're doing over there and there's no reason why people shouldn't know what we're doing. But the military does not like the press. Now in Operation Anaconda, they did bring media units in there and the funny thing is, that operation is just totally overblown into some great campaign. But it was really just a few thousand American troops looking for a few handfuls of al-Qaida holdouts.

Anaconda was made to be a big deal because they had to feed the media something. And so now the media thinks they have this great battle on tape and they were there and so on and so forth, but really nothing happened.

Do you think there's a lack of proper critical insight with regard to the military strategy in Afghanistan and U.S. conduct?

I think people who look into what's going on over there know what's going on. I think they understand how we fought this war and how many troops were engaged and what tactics we used and what weapons we used. I don't think there's any confusion about that. I think we've used a lot of Special Forces groups and a lot of normally covert operators.

I think the story of the CIA hasn't even been told yet. So we've done a lot of things over there that people will never know about. And the intelligence community may or may not release that information. But the important thing is that the more we know about a military campaign, the more comfortable we are about engaging in a war. It used to be that if one soldier got killed and you'd see it on TV, we'd pull our troops out. But I think the military's a little overly sensitive to that. And I think people are expecting casualties and they have no problem with frank and fair disclosure of enemy activities and friendly activities.

How would you characterize the CIA's involvement in Afghanistan?

It was quite robust. The operation actually was initially run by the CIA. The idea was to engage local warlords or commanders and then outfit them with Special Forces teams and a couple of Air Force guys to call in airstrikes. Because they're Green Berets, which are directly linked to the CIA, their job is to feed intelligence back to the Pentagon or CENTCOM and allow real-time decisions to be made by the commanders. And the interesting thing is that that actually worked. That was a very successful campaign. There was very little collateral damage. We sort of formed a general idea of how to fight wars in these regions, but it may not be appropriate for Iraq or the southern Philippines or other regions that we go to.

From your sense on the ground, from talking to contacts, and from a U.S. intelligence standpoint, is it really a question of finding a needle in a haystack when it comes to al-Qaida leadership?

They're irrelevant. The war is going through many phases. Originally, we all wanted to get to Osama bin Laden and then we were sort of embarrassed by the fact that not only could we not get him, but we had no idea where he is or what he does or what his organization is composed of. And then we created a bogeyman called al-Qaida, which is sort of similar to the term "Mafia," sort of an all-encompassing term. And that's not really appropriate because most of the people over there are just foreign volunteers who are fighting either in Kashmir or inside Afghanistan. And we've blown this international conspiracy way out of shape; it's really not as big and as mean and as well-financed or as intelligent as our government makes it out to be.

Do you think the government knows what it's doing in that regard? Is it blowing them out of proportion on purpose or are they really just getting up to speed?

They're learning quickly. On Sept. 11, they knew nothing about it. And the reason I know this is because some of my friends work within those organizations and they just didn't want to believe that it existed because it was just such a small Mickey Mouse outfit. And after Sept. 11, they realized that even minor groups could have major implications. But instead of just always knowing that it was a small Mickey Mouse outfit, now they made it into this huge global conspiracy, which it isn't. Which has created all kinds of problems in the Muslim world because we're sort of demonizing the wrong people. The bad guys are living in America and Saudi Arabia and Germany and the U.K.; they're not sitting in caves in Afghanistan.

So what's the way out for significant American troop presence in Afghanistan?

There is no exit strategy. It's absolutely identical to what the Russians did. People respond to what they think is an opportunity. In this case it was an opportunity to overthrow the Taliban leadership, and once you get in there and you destabilize a country, you have a choice: You leave immediately, which would bring down a lot of grief on your heads from the world community, or you stay and try and figure things out. The staying and figuring things out part is a lot more difficult than going in and destabilizing a fairly backward regime. The only thing that concerns me is when George Bush gets full of himself and starts expanding our war to include places as bizarre as North Korea and Iran and Iraq, but doesn't include a lot of the known harbors and supporters of terrorist groups. That makes me nervous.

What are you hearing about us going into Iraq?

They tried to, and then they got told: "You've got to be kidding."

You think Cheney got rebuffed on his trip to the Mideast?

God, yeah. The thing that's important to understand is that the American government knows about as much as the American people know about how to prosecute this war, which is nothing. We're learning day by day what works and what doesn't. The thing that's happening is that there are huge military expenditures occurring, which tends to be an animal that needs to feed itself, and that's the part that's bothersome. Like in Vietnam. We started by sending over advisors and helping a regime support itself, and we ended up sending half a million troops over there and really accomplishing nothing.

What happens is that the intent of the American people is correct, because we did read about and hear about things and we saw things on TV that shocked us so we responded. But we get bored; we have a, like, 120-day window in which we give a shit. After that period, we get bored and we watch something else. I think I saw a shark-attack story on TV yesterday.

We don't realize that we went from spending zero to millions of dollars a month in a foreign country to prosecute a war and we're really not fighting a war, we're just sending more and more troops over and flying B-52s around in circles and so forth.

That's the part that the media has to keep up on -- what are we getting for our money? I mean, have we kicked out the bad guys? Shouldn't we be attacking Pakistan, isn't that where all the bad guys come from? I mean there's this amazing disconnect between common sense and government rhetoric. Most of the people who were killed in Afghanistan were Pakistanis, not Afghans.

But they're saying that having American troops running around on the Pakistani side of the border is not going to happen.

But the media needs to wake up and say, "Hey, wait a second. We're supporting a military dictator who took power in a coup, who's one of the main sponsors of terrorism, who paid for the camps over there, who's educating and entertaining and training thousands of militants to go fight inside Afghanistan against us." It's like, whoa, wait a second, why is he our best friend?

What happens is that the media gets host-friendly. So when the military sends you over to write stories about things, they want you to also make a note that Pakistan is our loyal ally and that they're vigorously prosecuting the war on terrorism.

But when you look at Daniel Pearl, he wasn't kidnapped by Afghans. He wasn't murdered by Afghans. He was murdered by people with strong and lengthy links to the Pakistani [intelligence agency, the] ISI.

At first the media complains because they're not getting enough information, they're not being allowed to cover the war. Then when they get to know everything, after the 120-day window, nobody cares anymore. Because once they start spelling it out and saying, "Wait a second, these guys are all from Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Why aren't we fighting a war in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan and Egypt? Why are they our allies?" And then those are the tough questions that never really get asked, because the public doesn't really care at that point.

Surely these big-time reporters have these questions and are asking them.

That's not true. You ask Barbara Walters. Why was Barbara Walters in Saudi Arabia? Did she get up one day, buy a ticket and take a camera in with her? No. She was invited by the government as part of a P.R. campaign to convince the American public that the Saudis who flew the planes into the buildings had nothing to do with the country of Saudi Arabia. That's an overt P.R. campaign. Why do you think the military invites journalists into a combat area? Because they know there's going to be a nice clean operation and it'll look good when we blow stuff up and they'll write about how we're winning the war.

What are you going back to Afghanistan for?

I'm going to be working on a documentary about the uprising at Qala Jangi. So we're going to be interviewing people who were there and using footage that was shot, that strangely enough has never been pulled together into one documentary.

I assume you'll be using the footage of [CIA agent] Mike Spann interviewing Walker.

The footage starts out much earlier than that. It starts out with the surrender of the Taliban and then the actual fighting inside the fort and then the initial uprising and so on. So when you ask about the government, even the government hasn't collected all that information together. And you'd think that with one of their people murdered there ... and they still have never contacted people to get that tape or find out what happened.

So they're still dragging their feet?

They're not dragging their feet, they work for the government. People who work for the government choose deliberately to work for the government and the government is its own little world. I mean, if Mike Spann was a friend of mine and he was murdered there, I would probably get more together in the first couple days than the entire government would. They just don't have the resources or the energy or the ability to do things.

Do you think Afghanistan has a chance at a legitimate government?

Yeah, if they start writing checks to Afghans. The problem is they're writing all these checks to Americans. They just wrote a check for $6.5 million to a university in, I think, Nebraska or something to create textbooks for Afghanistan. Well, Christ, for that kind of money they could set up an entire printing outfit and fly people over there to set up a state-of-the-art document processing system.

Is that part of being beholden to America in terms of security?

No, that's just the way wars work. You don't fight wars because you're a nice guy; you fight wars to make money.

And Hamid Karzai thinks: "I'll give some back to America"?

He has no choice. He works for America. He doesn't have any power base inside Afghanistan. Nobody elected Karzai. He was selected by the Americans because he's an English speaker and because he's a nonmilitant person. But he doesn't have a military authority to run Afghanistan. It's as simple as that. He just popped into position and they brought a bunch of people over that supported the king, who hadn't been in Afghanistan in years if not decades, and they magically made him in charge of the government. A lot of the aid is going to be directed toward American companies that then go back into Afghanistan to make money doing what they're doing.

Do you see people over there doing good jobs on the ground?

There's a guy, Dodge Billingsley, who's a cameraman who just goes wherever the hell he wants and he was the only guy to cover the combat in the initial stages of Anaconda and he was also inside the fortress, shooting the uprising, but he's not paid by anybody, he's just his own guy.

You'll find that almost all the footage was shot by small independents, not by any major network ... the message to journalists is: Don't ever expect a big dumb corporation to just send you somewhere because you have a hunch. Those days are over.

So get there yourself?

There's a sliding scale of limitations. You can get there yourself, but you won't have a satellite. And just something as mundane as not having a satellite phone to call people back will limit your ability to make an impact. When I was in Chechnya with the rebels during a siege, there was nobody there, just me and the guy I brought in. But nobody cared, because there weren't enough journalists there.

It's not a story until the press corps gets there.

Exactly. That's the way it works. When the uprising happened at Qala Jangi, there was stunning enough footage that people said: "Whoa, what the hell's going on there?" And it became a story, because I think it was the first sort of combat footage other than the little bit of stuff that was in the Kabul area. And then once everybody flocked there, then they sort of made it a news story. They sent Christiane Amanpour to Kabul to basically sit and do all those silly stories they do all the time about demining and zoos, and there were enough people there that they had feeds every night from ... I mean, shit, they had Ashleigh Banfield there, I think, for a while. So it became sort of the big story.

Do you essentially pay for all your own trips?

Well, I have a TV series that runs on the Travel Channel, and I write a book. I would never expect ... even if I called CNN up right now and said, "Hey I want to go here," they'd say, "Well, OK, let me think about it." You never get any kind of autonomy even though you know what's going on. Because news is not necessarily driven by news. It's driven by what people want to watch. I said: "I want to go to the Pankisi Gorge [in Georgia]." And they said: "No, I think that's too much war for people to figure out." Because they can only handle one conflict at a time. You see how much footage comes out of the southern Philippines: nothing. Or Yemen, it's zero.

There's obviously stuff going on there. Special Forces troops are there. But let's say you wanted to go there tomorrow with a camera. Would you be able to go and hook up with those guys?

Yeah, but technically they're not allowed to talk to me. I mean, I'm allowed to talk to them. And some of them have tried to tell journalists not to photograph them, which is kind of laughable. But the bottom line is, nobody's stopping you from hanging out with the rebels. And there's nobody stopping you from going out with the Philippine military or whatever.

Where are you headed after Afghanistan?

I'm going to have to go back to Chechnya and then Colombia, and I might go to Yemen, because I find that fascinating.

Shares