Studs Terkel didn't invent the oral history, but as far as modern journalism is concerned, he might as well have. His 11 books of interviews with people from all classes and all walks of life -- about subjects ranging from race to religious faith to World War II, the Great Depression and the world of work -- when considered together, make up one of the greatest documentary projects about American life of the last century.

Terkel is certainly most famous for "Working," in which he interviewed gravediggers, designers, schoolteachers, washroom attendants, truck drivers, dentists, switchboard operators and countless others about "what they do all day and how they feel about what they do." The idea for the book (as for most of his books) was so simple that its most extraordinary aspect was the fact that nobody had ever done it before.

As influential -- and as eye-opening, often hilarious and sometimes devastating -- as "Working" was, all Terkel's books are remarkable explorations of the lives of "ordinary" people (he doesn't like the word). "'The Good War'" offers a compelling account of World War II, both from a grunt's-eye view and on the home front. "Hard Times" may be the most compelling and convincing single book about the Great Depression of the 1930s. But many readers consider "American Dreams: Lost and Found" to be his greatest work. In that book, he interviews people both legendary and obscure, from immigrant farm workers, embittered beauty queens and Ku Klux Klan members to Arnold Schwarzenegger, Joan Crawford and Ted Turner. The novelist Margaret Atwood wrote that it contained "raw material for 1,000 novels in one medium-sized book!"

Terkel was born in 1912 in Chicago (as he puts it, "the Titanic went down and I came up") and has spent most of his 91 years of life in what Carl Sandburg immortally called the "City of the Big Shoulders." His view of the world is unashamedly proletarian, proudly left-wing and small-D democratic (he has his doubts about the Democratic Party at this point), profoundly Chicago-centric.

Yet Terkel's work only sounds like it's going to be p.c. and dull when you haven't read it. He is never afraid to engage those whose views differ from his own and he's a delightful natural storyteller who is always more interested in people than in ideas. His new book, "Hope Dies Last: Keeping the Faith in Troubled Times," is probably his most abstract work and at the same time his most personal.

Ostensibly, "Hope Dies Last" is a book about dedicated political activists, the "prophetic minority" who Terkel says are capable of imbuing their society with hope and moving it, ever so slowly and gradually, in the direction of justice and decency. It also feels like a summing-up, a tour of Terkel's great preoccupations: the labor movement, race, economic injustice, the generations who emerged from the great turmoils of the '40s and the '60s. It's full of inspirational tales -- Terkel is never ashamed of his agenda, and he's trying to convince his readers that social change is still possible -- but is never saccharine.

Terkel talks to Rep. Dennis Kucinich, the Ohio Democrat (and current presidential candidate), whose family lived briefly in a Packard automobile when he was a child, and to Rep. Dan Burton, the Indiana Republican, who has horrific memories of his father beating his mother before his eyes. He interviews retired Adm. Gene LaRoque, a persistent critic of the Pentagon, and also retired Gen. Paul Tibbets, who personally dropped the A-bomb on Hiroshima and has no regrets.

Terkel's other interviewees in "Hope Dies Last" range from Chicago schoolteachers to activist Southern preachers to food writer Frances Moore Lappé, Oakland, Calif. mayor (and former California governor) Jerry Brown and legendary economist John Kenneth Galbraith -- at 94, the one person in the book older than Terkel. The vision of hope that emerges from the book is never easy and always constrained by painful circumstance, but far more real, and more affecting, because of those limitations.

When Terkel interviews Leroy Orange, a man who spent 19 years on death row for a murder he did not commit before being pardoned in 2001 by Illinois Gov. George Ryan, Orange actually says he is grateful for the whole experience. His experience with the justice system, he says, had brought him close to hopelessness and given him a "racist attitude"; he believed a poor, black defendant like him had no chance. When white activist lawyers began to work on his case, he didn't trust them at first, but eventually realized that "just like there are white people who fight for the wrong causes, there are just as many who fight for the right causes." He might never have learned that without going to prison in the first place, he suggests, and "it makes you feel something good about mankind." Hope dies last, indeed.

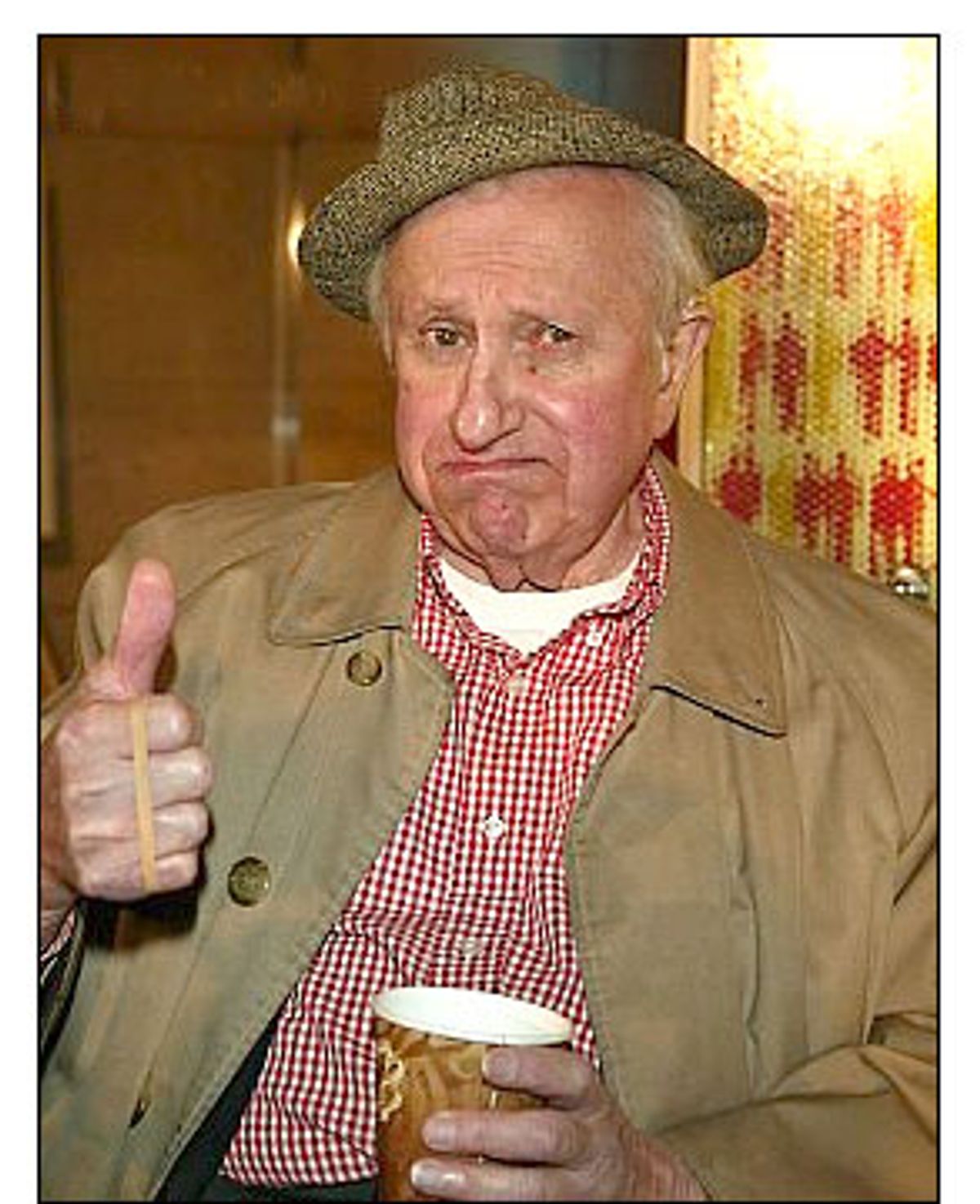

I caught up with Terkel by telephone in his New York hotel room amid a whirlwind book tour. Our conversation is presented here Terkel-style, without interpolated questions or comments. There's another reason for that besides paying tribute to his method: Terkel is such a raconteur he barely lets you get a word in edgewise (and you don't want to). The only thing I clearly remember saying to him was that it was a little intimidating to interview such a famous interviewer. "Who, me?" he said. "I'm just a goofball doing the best I can."

Except for his hearing loss (which he frequently bemoans), his manner is that of a man 30 years younger. He said he was sorry we hadn't met in person so he could act out various of his anecdotes. So when this titan of American journalism -- and this "ham actor," as he calls himself -- says he thinks he may only have one more book in him, one has reason to hope he's wrong. There's that word again.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Let me put this old hearing aid on, I'm as deaf as a post. I'm a Luddite, yet I'm a slave to technology!

Now I think I hear you. I know about your Web site, my son tells me about it. And the Internet has a marvelous democratic possibility. I'm aware of all that, but I haven't the vaguest idea. I'm just learning the wonders of the electric typewriter. It's fantastic!

My new book is called "Hope Dies Last." I must have been crazy to try it. But something just occurred to me and I had to do it. Years ago, in an earlier book, "American Dreams Lost and Found," I interviewed an old Mexican farm worker, Jessie de la Cruz, who was one of the first women to work with Cesar Chavez. And she said there's a saying in Spanish when times are bleak or bewildering: La esperanza muere última. "Hope dies last." And somehow the damn thing stuck with me.

Remember, all the other books have dealt with visceral experience, something you could put your hand on. The Great Depression: What was it like to be a little kid, 10 years old, who sees her old man come home with his toolbox on his shoulder, a good carpenter, and then he doesn't work for the next five or six years? Until the government comes along, the New Deal! When free enterprise -- it's called the free market today, the new religion -- fell on its ass completely, and fell on its knees and begged the government to save it.

The irony is, the very ones whose daddies and granddaddies' butts were saved are those who most condemn "big gummint," as Molly Ivins would put it. Health, education, welfare. Not the Pentagon, of course! That's what I call the national Alzheimer's disease: There's no memory of it, it didn't happen really. All my books you might call memory books, trying to recreate a memory of what it was like to be that ordinary person -- a phrase I don't like, by the way; it's patronizing -- a non-celebrated person.

What was it like to be a mama's boy on a landing craft about to hit Normandy in '44? That was in "'The Good War'." Or to be a woman who has a job for the first time in her life, ironically enough because of the war. Or "Working." What was it like to be a teacher or a checkout clerk? Want to hear a funny story about that one, while we're at it?

This guy was a meter reader, a gas-meter reader. The one who comes in with a flashlight and goes in your basement. I said, "Tell me about your day." And he gets going: "Well, it's mostly dogs and women."

Then I realized, the first is the reality and the second is a fantasy. So I said, "Let's talk about the dogs first." He said, "The worst, you know, are the Pekinese and the poodles, the spoiled brats of dogdom. They're the ones who gnaw at your foot, and I want to smack 'em with my flashlight."

"OK," I said, "what about the women?" He said, "Well, nothing has happened, you understand? But it's one of those things in my mind. For example, you go to a house" -- and he named a suburb in Chicago, a nice suburb -- "and the lady of the house is very pretty. She's lying outside on the patio; it's a summer day. On a blanket, on her stomach. She's in a bikini and the bra is unbuttoned because she wants the sun to hit the whole of her back. So what I do is I creep up slowly, very slowly, and when I'm right next to her I holler, 'Gas man!' And she turns around!" And then he says, "I get bawled out an awful lot. But" -- here's the part -- "but it makes the day go faster."

I wanted to capture that aspect in "Working." All the other books, whether they're about race or coming of age or reflections on death, which is really about life, are all visceral, specific things. This book is about hope. The most abstract, it seems, and yet it turns out to be the most personal. It's my tribute to what I call the "prophetic minority," those who've been activists since the Year One.

You notice I dedicate the book to a couple whom you may not know, Clifford and Virginia Durr. They were a white couple living in Montgomery, Ala. She was the sister-in-law of [Supreme Court Justice] Hugo Black. And he was a member of the FCC [Federal Communications Commission], who wrote the "Blue Book" on the rights of listeners -- air belongs to the public! -- for as much variety of programming as possible.

Contrast him today to the FCC kid who's the son of Colin Powell, right? And Colin Powell, we know, is the African-American butler to the new Bertie Wooster. Bertie was a little milder than W., not quite so mean-spirited. He had a British butler, and Bush has one too. His name is Tony Blair. But his American butler is very elegant, and Powell's son is the footman at the head of the FCC. He lays out the red carpet for them. So now we have an FCC that says, "The hell with regulation! Clear Channel, you can own 10,000 stations if you want!"

We live in a crazy moment when the most powerful media mogul in our country, aside from Time Warner, is an Australian Neanderthal, Rupert Murdoch. So people are confused and bewildered; they seem lost and hopeless. So I thought, why not a book about all those who have had hope, and have taken their beatings and paid their dues -- but as a result of what they've done, something has happened.

That was the case with the Durrs, for example. They could have led easy lives. His was a prominent family in Montgomery, and she was the daughter of a clergyman. She had three roads to travel: She could have been the Southern belle, in "Gone With the Wind" fashion, been nice to her "colored" help and joined the garden club. Or she could have gone crazy, that is, being intelligent and thoughtful but doing nothing, as her friend did -- her friend Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, who was a schoolmate of Virginia's. You know Zelda went nuts, right? The third route was to say something was cockeyed here. The Depression taught her that. The other side of the tracks taught her that. She said, "I've gotta fight this," and she took the third path, the rebel girl.

Virginia -- I gotta tell you this story -- was a lanky, elegant woman. She was in Chicago -- this was in the '40s -- with a group against the poll tax [a tax imposed in Southern states to prevent blacks from voting]. She and Dr. Marion McLeod Bethune -- you've heard of her? African-American woman educator, friend of Eleanor Roosevelt -- were speaking at the Symphony Hall and it's jammed. Mrs. Bethune was fine, but Virginia was incredible!

So I go backstage and I go to shake her hand. I say, "Mrs. Durr, you were fantastic." She said, "Thank you, dear." And as she says that she puts forth her hand, and she's got a hundred leaflets! "Now, dear" -- without missing a beat -- "it was nice of you to come back. Hurry outside and pass out those leaflets. Dr. Bethune and I are at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in two hours. Hurry, dear!" So that's how I met her.

The next time, I saw a picture of her in the papers. Sen. Jim Eastland [a segregationist Mississippi Democrat] was jealous of Joe McCarthy, and he wanted his own committee to investigate subversives and commies. So he gets after the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, which was a group of Southern whites, mostly, who tripled the registration of blacks in the South. It was a remarkable group that also included Miles Horton, the founder of the Highlander Folk School. That's where Rosa Parks went. Rosa Parks was a seamstress for Virginia Durr. Virginia encouraged her to go to this school, which Martin Luther King attended, which was about helping labor organizers, black and white.

So Virginia was an unfriendly witness called by Jim Eastland to investigate this group. And there's a picture of her in the newspaper, with her legs crossed, and she's powdering her nose. There he is, all 300 pounds of him, furious and fulminating. She ignores his presence; he's not even there. The guy goes crazy and orders her off the stand. Naturally, all the reporters gather around her: "What did you do, Mrs. Durr?" She said, in that voice of hers, "That man is as common as pig tracks. I guess I'm just an old-fashioned Southern snob." But the fact is, she defied them, and Cliff did too. And they paid their dues: They went broke and they were ostracized.

Now we come to 1965, the Selma-Montgomery march, two years after Martin Luther King in Washington. You know of that? They had 200,000 people converge on that march from Selma to Montgomery! There was a celebration at Virginia's house in Montgomery -- 2 Felder Street, how could I forget it? -- that home was a home for waifs, everybody came in, even though they had no dough.

We were celebrating this tremendous event, which wound up at the mansion of Gov. George Wallace. We're watching Wallace on TV, excoriating the marchers and the leaders, and he names the people in the room, including Miles Horton. And then Miles says, "Isn't it funny? Remember 20 years ago, there were 15 or 20 of us and we'd be egged, tomatoed and threatened? We all knew each other. Today, I didn't know a single person there, and not one knew me. But isn't it wonderful? Two hundred thousand!"

That's what I mean by the prophetic minority. That's why I dedicated the book to them, and the book deals with those kinds of people, who we call activists. Who are imbued with a sort of hope and craziness, you know -- who some way or another hope our society, or the world, will be a more decent place to live in.

I think perhaps at this moment it's more important than ever. They encourage the rest of us; this is the big thing. They imbue all the rest of us with hope. Feb. 15, 2003 -- I celebrate that day because 10 million people all over the world came out against the preemptive strike [against Iraq]. And then there was silence, because for three days it looked like W. was the liberator of Iraq. Then, well, we know what happened.

The one who closes the book is Kathy Kelly, the founder of Voices of the Wilderness [an antiwar activist group that often "bears witness" in war zones]. Kathy was teaching at a wonderful parochial school in Chicago, St. Ignatius. Then she decided that she's not gonna pay the taxes that go toward war. [Kelly voluntarily accepted a salary too low to be taxable, and the school donated the rest of her customary salary to charity.]

Kathy's a disciple of Dorothy Day, who was asked the same question Kathy was asked, the same question Virginia was asked: "Why are you doing this? You could be leading a nice, easy life!" Kathy's reply was: "I'm working toward a world where I hope it will be easier for people to behave decently." You can't beat that.

The story I love to tell is about Kathy and one of our GI's. She goes to a missile site, and you've seen a missile site. One of those banal little hills. She goes to Missouri, it's corn country, but there's no corn there because of those missile sites. Kathy being Kathy, she cuts through the damn barbed wire and she goes to the missile site and she puts up that sign from the Old Testament prophet Isaiah: "Beat your swords into plowshares and study war no more."

Then she calls up the authorities. She's violating the law! She weighs about 85 pounds, dripping wet. So here comes the big arsenal. The commander, maybe the brigadier general, calls out: "Will the personnel on the missile site get off with your hands raised! Kneel!" And she does, and they handcuff her. So here comes this kid, he's about 19 years old, off the truck, with his gun at her head. And he's trembling, because here's the enemy! All 85 pounds of her! He's scared of her; she's a terrorist!

She's kneeling, handcuffed, and she looks at the kid and says, "Do you know what I'm doing?" The kid, he's a country boy, says, "What?" She says, "I'm praying for corn to grow here." She had planted some seeds. She says, "Wouldn't you like the corn to grow here?" And he says, "Yes, ma'am." She says, "Will you pray with me for the corn to grow?" And he says, "Yes, ma'am."

So they pray for the corn to grow. And it's a broiling hot day. The kid looks at her -- she's still got the gun at her head -- and says, "Ma'am, are you thirsty?" She says, "Oh, God, yes I am." So he lays down the gun, which I assume is a violation, and he opens his canteen. "Ma'am, will you lean your head back a little?" And he pours the water into her mouth, as she describes it, like putting worms into a little bird's mouth.

When she goes to court, she sees him there and she winks at him, and he's trembling, because he thinks she's going to tell the story. So in the book she says, "I'm telling it to you, and I hope that if this boy reads this book, he'll forgive me for exposing him."

So this book is about people like Kathy and the Durrs, those today who imbue the rest of us with hope. One thing I forgot to put in -- you know, I work very improvisationally, in a jazz kind of way. There was an investigation at Leeds University in England where a psychologist or psychiatrist comes up with the idea that when people take part in a community action, something good happens to them physically. That it's good for your actual physical health when you take part in something, because you feel that you count, that you're somebody.

My favorite from the American Revolution, of course, is Thomas Paine, who was admired very much by Washington and others. He spoke about a whole new society, the United States of America. There never had been a society in which a cat could look at a king, you know -- and then tell the king to go bugger off. Here was a new society that would lift us like Archimedes' lever, that could lift the whole world.

This particular society would look at man in a new way, not with the perverse idea of being inhuman and the enemy, but as being kindred. Of course today it's precisely the opposite; this guy [Bush] sees the axis of evil everywhere. We, once the most admired country in the world, are now the most feared and -- let's face it -- hated.

If ever there were a time for these people, who I've admired for years, this is it. There was Tom Paine, there were the abolitionists. In the '60s there were the African-Americans who fought for civil rights, the kids against the war. Who were a minority, remember; the jocks beat the shit out of them at first and then joined them later. That's what I mean by a prophetic minority.

It's not a Pollyanna book. I am optimistic, but the word is "guardedly." Guardedly so. I mean, three of the bestselling books are Al Franken and Michael Moore and Molly Ivins, all at the same time. That's not bad. It's an indication to me that there's something underneath, that the people are way, way ahead of the political leaders and the pundits.

You say you hope I'm right. You hope. I hope too. I hope I'm right. I'm not saying I'm right.

I see now that this is the most personal of my books. And people are really affected by it. I'm also a ham actor, so I do this in bookstores all over the country. Like last night in Barnes & Noble [in New York]. And it was fantastic! The Bay Area cities: OK, I knew Berkeley was gonna be OK. But I didn't expect San Jose State to be the way it was. It was students, and it was astanding O -- I'm just saying that, because it was.

They're ready for something, provided it's said directly to them. If the Democratic Party loses this one to Bush, with wars and a forthcoming depression -- Hoover just had a depression -- if he wins and the Democratic Party, to use an old Poe phrase, deliquesces like fungi, then that's it. That's enough.

There's a poem by Brecht: "Who Built the Seven Gates of Thebes?" When you ask who built the pyramids, the automatic answer is: the pharaohs. But the pharaohs didn't lift a finger. I was told, by Mrs. O'Reilly at McKinley High School in Chicago, that Sir Francis Drake conquered the Spanish Armada. He did? By himself? Brecht in the poem says that when the armada sank, we read that King Philip of Spain wept. Here's the big one: "Were there no other tears?"

To me, history is those who shed those other tears. Those whose brains and whose brawn made the wheels go around. I hate to use the word "the people." The anonymous many. But they're it. I know that the Internet has all sorts of democratic possibilities: That's how Howard Dean came up so fast, isn't it? At the same time, there's a fear of so much in the hands of so few.

I was also going to talk about the perversion of our language: To go more "moderate" means to go more toward the center, and to go toward the center means to go toward the right. If you could see me now, I could do a demonstration: If our physical posture followed our political posture and the perversion of our language -- I'd have to act this out -- we'd walk around leaning to the right. That's the normal way of walking. And then, the guy who's walking straight: "Look at that leftist!" Or if the guy who's walking straight leans a little bit to the left: "He's a goddamn terrorist!"

I've given you a rambling account, I suppose, of why I undertook this particular book. I think I've got one more book in me, although I must be crazy. I mean, I'm 91 years old: the Titanic went down, and I came up.

I was a DJ in Chicago once, and I loved to play all different kinds of music: jazz, classical, whatever. I introduced Mahalia Jackson's music to a lot of people, and we were great friends. I mean, she would have become known without me, but she used to say that. So I'm doing a book on music, simply called "They All Sang."

It'll be not only singers: Alfred Brendel, Segovia, as well as Larry Adler. It'll be that kind of book. I did an interview once with a kid, 20 years old, named Bob Dylan. The legacy of Pete Seeger's family, an old musical family. So we'll see how that goes.

And then I'll check out. I'll tell you what, I'll give you my epitaph. It's a simple one: "Curiosity did not kill this cat."

Shares