"Truth, I have learned, differs for everybody," opines Oelph, the slightly pompous narrator of Iain M. Banks' new novel, "Inversions." "Just as no two people ever see a rainbow in exactly the same place -- and yet both most certainly see it, while the person seemingly standing right underneath it does not see it at all -- so truth is a question of where one stands, and the direction one is looking in at the time." If that's not a warning against unreliable narrators, I don't know what is. The Pontius Pilate-like statement seems reasonable yet treacherous, calling into question its utterer's ethics. It's typical of Banks: In book after book, he takes as his themes betrayal, deception and loyalty.

Banks began his career in 1984 with "The Wasp Factory," a claustrophobic novel about a cruelly dysfunctional family. Variously confined -- to a madhouse, to a small island off the coast of Scotland or by their own warped intentions -- the family members struggle to express themselves by controlling one another's fate. Their self-realization takes dangerous forms: murder, arson and worse. The narrator, a lonely adolescent who enjoys burning wasps and blowing up bunnies, claims to have murdered three children, two of his cousins and one of his brothers. The methods he used are ingenious if incredible: hiding an adder in a boy's prosthetic leg, tying a girl to a huge kite and letting her blow away. He describes the murders matter-of-factly, though with a tinge of pride, as if any sensible person in similar circumstances would have done the same thing if he'd thought of it. Compared to his surviving brother, an asylum escapee who burns dogs alive, the narrator considers himself the sane one.

While it's bone-chillingly weird, "The Wasp Factory," one of more than a dozen novels by Banks, takes place on Earth and follows the familiar laws of physics. He also writes science fiction. These novels -- the ones I've read, at least -- share with the "literary" books their author's twisted imagination and his fascination with deliberately inflicted pain. Yet because the conventions of science fiction are so much odder than those of straight fiction, Banks' science fiction books seem more conventional. In them, he wraps his psychological concerns in crisp, imaginative prose, suspenseful plots and plausible -- or at least enjoyable -- technology.

Readers who like spaceships, worm holes and intrusions from other dimensions might want to start with "Excession," a 500-page sprawl with the obsessive structure of a paranoid fantasy. The Culture, a loose hegemony of societies made up of biological and machine-based individuals, is alarmed to discover an excession -- a small oval object that seems to have come from another dimension. Worried that the intruder intends to take over the universe, the Culture sends in its crack intelligence team, a club of Minds -- immortal spaceships who wisecrack and conspire like a chatroom full of insomniacs. Word leaks out, war starts and the plot gyrates, showcasing Banks' obvious delight in teasing his characters.

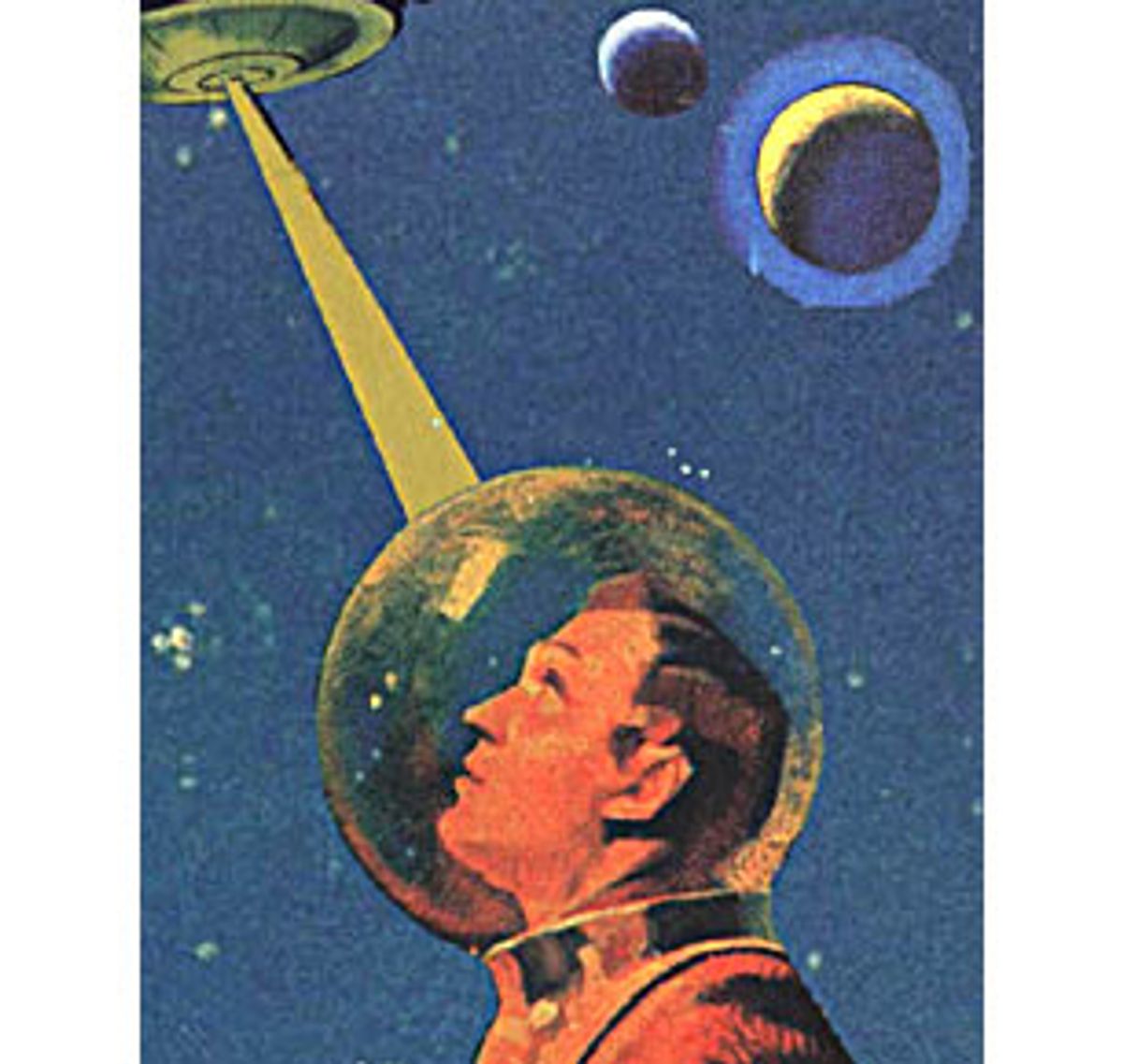

The new novel, "Inversions," is a much more tightly structured story in the political-intrigue-on-a-foreign-planet subgenre. On a world that many inhabitants still believe to be flat, feudal leaders of regions formerly united under an emperor plot to gather power into their own hands. Their spies often find it wise to save their most nefarious acts for the rare nights when all six moons are dark.

"Master, it was in the evening of the third day of the southern planting season that the questioner's assistant came for the Doctor to take her to the hidden chamber, where the chief torturer awaited." So writes Oelph, the apprentice to King Quience's personal physician. The "master" he addresses is an unnamed figure presumably in the king's court, and part of "Inversions" takes the form of Oelph's secret reports to this shadowy person. They alternate, chapter by chapter, with another account of palace intrigue, set half a planet away in Tassassen, another fragment of the former empire. The second story centers on a figure named DeWar, bodyguard to General UrLeyn, prime protector of Tassassen. It's not clear until near the book's end what the two strands have to do with each other.

Anyone might be a spy; we know Oelph is. Has he betrayed his mistress (already, on the first page of Chapter 1)? Is she about to be tortured? The doctor has many enemies. For one thing, she's a foreigner, whose origins are never completely explained. As the king's personal physician, she has his ear. It's an unheard of position for a woman, one she won with her healing skill. Unlike all the other physicians in Quience's kingdom, who believe in humors and bloodletting, she holds with what readers will recognize as the underpinnings of modern medicine: germ theory, scientific method, the importance of washing your hands before cutting into a patient.

Dr. Vosill's medical rectitude stands for and reinforces our gradually building sense of her moral rectitude. Oelph, it becomes clear, is in love with her. She seems to trust him entirely, confiding in him and teaching him her medical secrets. So why does he file reports on her, and even steal one of her scalpels to hand over to his "Master"? Who is this master? What binds Oelph to him? Does the king deserve Vosill's devotion?

Parallel to Vosill's story, DeWar's gradually reveals layers of scheming and disloyalty. Like Vosill, DeWar has come from a far land -- the same one? -- to serve a ruler in an intimate capacity. As UrLeyn's bodyguard, he often risks his life for the general. Only Perrund, a favored concubine, shares as much of UrLeyn's trust. She lost the use of one arm saving him from a dagger blow. Yet the general's fortunes are falling, and someone close to him evidently wishes him ill. It's a fascinating puzzle to sort out the goodies from the baddies, when Oelph's creepy vision casts a shadow over everyone's agendas.

For Banks, the question of betrayal ultimately comes down to motive. If you win your enemy's trust, what do you owe him? What's fair in love and war? By giving his characters a constellation of contradictory loyalties and requiring them to choose, Banks obscures the distinction between good guy and bad guy, allowing him to pack his endings with drama and unease.

Shares