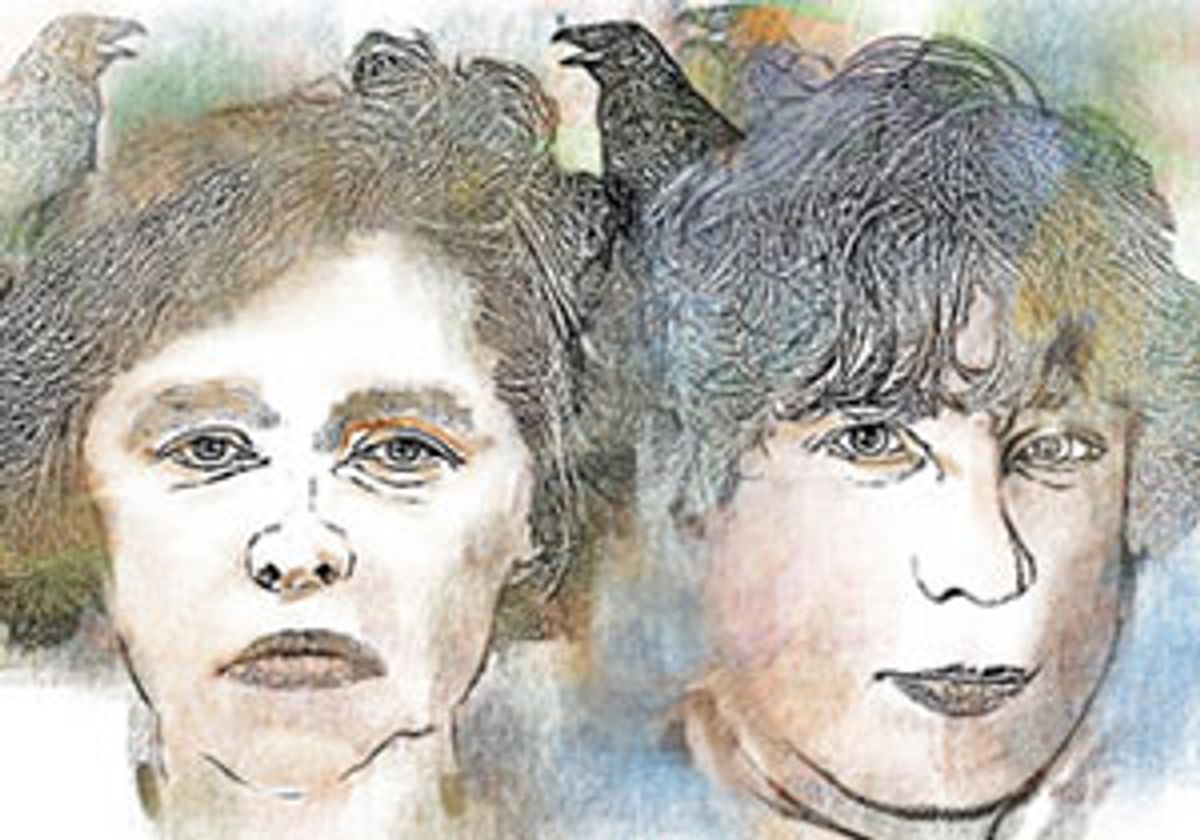

Writers are legendarily competitive, and frequently petty about it, as countless romans à clef have shown. That makes the sunny collegiality in the friendship between Neil Gaiman and Susanna Clarke most remarkable. Gaiman -- who somehow manages to qualify as a cult writer despite regularly landing books on the bestseller lists and drawing crowds at his public appearances -- first read Clarke's work over a decade ago, when an old friend, Colin Greenland, sent him a sample. Clarke, who loved Gaiman's "Sandman" graphic novel series, had signed up for a writing course largely on strength of the fact that Greenland, who taught it, knew Gaiman. Gaiman was so taken with the scrap of fiction Greenland sent him that he demanded to see more. He kept sending Clarke's work to publishers and was eventually rewarded, along with all the rest of us, with "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell," Clarke's doorstop novel about two rival magicians, published to great success last year. Gaiman says that for him the best thing about Clarke getting famous is that when people ask him who his favorite contemporary writers are, he no longer has to explain that one of them hasn't published a book yet.

Gaiman and Clarke write in an imaginative tradition that, as they see it, goes back centuries, although the "fantasy" label now affixed to it is a recent development. It's not always a comfortable fit when so many readers associate the genre with pallid Tolkien derivatives. Gaiman, for example, chooses mostly contemporary settings for his novels, often scruffy urban ones like the London Underground ("Neverwhere") or the ramshackle roadside tourist attractions that inspired "American Gods." His latest novel, "Anansi Boys," is like a cross between Nick Hornby and Zora Neale Hurston, based on West African and Caribbean folklore but set in today's London, and he is the screenwriter for "Mirrormask," a new animated film about mother-daughter friction by Dave McKean that wanders in and out of a decrepit public housing complex. Clarke won over many elf-averse readers with her uncanny ability to re-create the prose cadences and ironic wit of classic 19th century novelists like Jane Austen and Anthony Trollope; her novel is as much about manners and politics as it is about spells. The two authors, in New York to do an onstage interview, met with Salon beforehand to talk about their shared enthusiasm for British folklore, the tyranny of realism and the cat flaps of Isaac Newton.

Do you two feel a particularly strong kinship with each other's work?

S.C.: Especially between "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" and a book Neil wrote called "Stardust."

N.G.: I think it's because they're English.

How so?

N.G.: Both of us like primary sources.

Such as?

N.G.: Well you read folk tales, you browse your way through Katharine Briggs. And Shakespeare. You get the sense of a peculiarly English fairy that's amoral and huge and at the same time incredibly small. There's a weird change of size and shape. It's a peculiarly English thing.

I should interject, for those who don't know this, that in English folklore, a fairy is not a tiny adorable girl with wings, but often a full-size person, and usually very capricious, powerful and dangerous -- someone you don't want to get mixed up with. England certainly has a modern tradition of fantastic literature that overshadows the rest of the world.

S.C.: Other European cultures have more developed myths and legends. You can get this feeling of the English or Scottish or Irish or Welsh fairy, but it is by nature very elusive. It would be possible to pin down a German fairy, but the English one just vanishes, becomes the shadow under the trees.

N.G.:There's a glorious short story that Susanna did. Was it Mrs. Mab? The one where she keeps going into houses which turn into the insides of flowers and nuts.

S.C.: The character keeps looking for Mrs. Mab. When she sees something and it's small, it looks big, and when she sees it and it's big, it looks small. It exists, but exactly where or what size it is is not clear.

Do you make this material up or do you go back to the folklore?

S.C.: I do go back to the folklore and to Katharine Briggs. That's the only bit of the magic in "Strange & Norrell" that I really researched. English folk tales and fairy beliefs are very fragmentary. Scottish, Irish and Welsh are a bit more developed. They have more remnants to pick at. Obviously, though, you also pick out stories from books you've read as a child. So I can't say I've been absolutely strict about it. It's just what's useful at the moment.

Do you think it's the lack of a developed folk tradition that spurs the imaginations of British writers?

N.G.: We don't know! We can lie, though. We're writers.

S.C.: That's the theory I'm beginning to come up with.

N.G.: It gets really interesting when you start trying to look for English folk tales. You wind up in places like the Appalachians, reading the Jack stories. Except the Jack stories in the Appalachians have no magic. It's all gone. So you think, well, they were telling these stories in England and the king in them would have been a real king, not the rich man at the other end of the road. Reading any book of English folk tales, what you're mostly struck by is the grumblings of the people who in the 19th century went out on the road trying to collect them and discovered that all they had was bits of stuff that had come over from [the Brothers] Grimm or [Charles] Perrault that people had been reading and passing on.

S.C.: There's a bit more than that -- things like Black Annis and the Blue Hag -- but it's very localized. They're not quite tales.

N.G.: They don't turn into stories. They're lovely fragments. It's almost like England has to cope with something big that's been lost. Take Stonehenge: I get irritated when neopagans start talking about the ancient legends of Stonehenge and how far back they go. When I tell them that those legends mostly come from the 1850s, they get really upset. In "Remains of Gentilism and Judaism," which is John Aubrey's book, he went out and found every single thing he could and wrote it down -- everything that was commonly believed about Stonehenge, which was if you chip a rock off Stonehenge and put it in your well, it will keep toads away. That's it. That's everything John Aubrey was able to find in the 1640s.

Why is that?

N.G.: Dunno. But if you're a writer you definitely wind up trying to create stories out of it because it's the raw material of story.

S.C.: I think the stories were there. The Grimms worked quite early on, and I think the people who started collecting English folk tales came a good bit later.

N.G.: It's like squirrels. The gray squirrels came in and they were more efficient than the squirrels that were there before. Grimm's fairy tales, by the time they were honed and put out there, were incredibly efficient.

S.C.: That's true. They were published in Britain and they were read by children everywhere. Maybe they ate up everything that came before.

N.G.: You look at Shakespeare and "A Midsummer Night's Dream," and it's obviously drawing on a body of stuff that is common. We have bits of things, like the Robin Goodfellow song from the same time. It's from the same thing, from a bunch of stories, from a relationship that people had with fairies. You go into Katharine Briggs and you may discover that portunes were these incredibly small old men who ate frogs that they roasted in coals, but you don't really learn any more about them.

Then there's this strange identification, which is I think a particularly English thing, between the idea of faerie and the idea of the dead. Again, it's not the clear-cut thing you have in most countries. There is this weird idea that the land of faerie may be the land of the dead. Perhaps it's where the soul lives.

S.C.: There are stories about people who while walking stumble upon a gang of people dancing. At the point at which they would realize that these are fairies, they would recognize someone they knew who was dead or someone who had been thought to be dead. It could be either. It could be that a live person had been stolen away.

After I read Stephen Greenblatt's book on Shakespeare, "Will in the World," I was struck by the association of the north of England with Catholicism, this old, suppressed religion associated with mysteries and ritual, sometimes practiced secretly. There's a parallel to "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" with the north being associated with the Middle Ages and with magic. It seemed like only the latest iteration of the religious history of England, with one religion supplanting the other and driving it underground.

N.G.: That was occurring in England all the time. It's a very English thing. Everything occurs in layers. And also the old stuff gets pushed to the edges, the north and the west.

S.C.: Or to aristocratic families who are rich enough to stave off any awkward questions.

N.G.: You'd need a hole big enough to hide a few priests in.

S.C.: And whatever it was that had been suppressed would tend to get put on fairies. Somewhere, I think in Aubrey, they asked people what religion the fairies had. At that time England was all Protestant, and they assumed that the fairies were all following the old faith, whereas when England was Catholic, it was assumed they followed what came before that. They were always antiestablishment.

They also seemed to be holdouts against a rising tide of rationalism on behalf of a magical past. Protestantism tried to purify Christianity of mysteries and priests and to ground itself in a direct relationship with the Scripture.

N.G.: Then again, the English didn't go for Protestantism because of all that. They went for it because it got them a kind of cheap Catholicism and a happy king. The oddness of it is that England went Protestant because Henry VIII wanted a divorce. It's not a country full of sensible Swedish people.

S.C.: But that's not to say there weren't those kinds of intellectuals there. They came along afterward and rationalized it. Well, it was a mess.

N.G.: You've always got a mess in England. That's the fun of it.

We've been talking about the English folklore, Neil, but lately you've gotten outside that. "Anansi Boys" is Caribbean. How does it feel to be writing from a tradition that you're not personally rooted in?

N.G.: For me, my previous adult novel, "American Gods," was very much about what happens when you're English and you come to stay in a country that you've seen in movies and on TV and think you know everything about, and suddenly you're noticing these odd little bits that nobody else notices because they grew up with it. And you think it's weird. You say, "Don't you think it's weird to park a car out on the ice every winter and wait for it to melt and fall in?"

Those little cultural differences can really make an impression. I remember being astonished by how many flavors of potato chips they have in England.

N.G.: Gherkin! The English grow up with pickle-flavored potato chips, so I probably wouldn't think to put them in a story. With "Anansi Boys" it was frustrating. I had the idea for the story first. I had Anansi [a West African trickster god], his son Spider and this other one who eventually got called Fat Charlie. Then I spent about seven years lazily reading every Anansi story I could and finding a book from the 1920s, when someone went out to Jamaica and talked to people. It's out of print, but thanks to the wonders of the Internet, I was able to get a copy. Reading stories about Anansi and death, this was all part of it. And then I had to go out to the Caribbean. And then I had to go to my friend Nalo Hopkinson and say, "I am a floppy-haired, white English person and I'm going to be writing Caribbean dialogue. I need somebody to read this and make sure that I am not making an absolute idiot of myself." Bless her, Nalo read all of my dialogue and offered suggestions where needed. I didn't actually breathe a sigh of relief until I heard the audiobook with Lenny Henry reading it. Lenny's from Dudley, but his mother came over from Jamaica, and he does all the accents. And they all work.

I particularly like that fact that you never tell the reader that the characters are black. It's something I realized a few pages in, and that made me think about why I would assume they were white unless I was told otherwise.

N.G.: If you look carefully, you'll notice that all the white characters are described as being white. If you're raised in comics, when you go to prose, you think about all the things you can do in prose that you can't do in comics. And one thing is that in comics you can see what everybody looks like immediately. So I thought, I wonder what I can do with that? It's happening in people's heads. I wonder if I can write a book in which almost everybody is black, and play completely fair -- it's not a trick or anything -- but I'm just not going to say "Fat Charlie was a black 33-year-old" because you don't start a book saying "Fat Charlie was a white 33-year-old." You'll have to pick up on cues, and they will all be given.

S.C.: That's fascinating. I always start out saying exactly what everybody looks like. I don't know why.

There's a great scene in "The Phantom Tollbooth" where a character gives the hero, Milo, an envelope and tells him there's a sound inside it. And the author, Norton Juster, simply writes, "Milo looked in and sure enough that's just what was in it." He doesn't have to describe it.

N.G.: There are so many cool things that you can do with prose! It goes in through your eyes and goes straight to the back of your head and noodles. I love footnotes, because they change your relationship to the text and what's happening. I like the fact that I finished reading "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" absolutely fascinated with the question of who'd written it. Because it very obviously wasn't being narrated by my friend Susanna Clarke, here and now. It was narrated much the way I decided that "Stardust" was being written in 1930.

S.C.: Do you know who writes it?

N.G.: I don't. One reason I'd like to go back and write another story set in that world is that I might find out.

Susanna, your book is striking for its use of a kind of voice that is like the signature of the Enlightenment. It's the voice of reason that you have very common-sensically describing all these dreamlike things. It's really a voice that belongs to the birth of the novel. It's the root voice of novels.

S.C.: That's true, but I can't say it's in any way deliberate. It's funny, because I don't think of myself as a novelist. I think of myself as a writer. I tell stories. I kind of stumbled on that by trying to combine Jane Austen and magic.

N.G.: But even at the beginning of the Enlightenment, you've also got Isaac Newton, who was on one hand figuring out gravity and the motion of planets and also spending much of the rest of the time on alchemy and magic. Also, he was famously the man who built two cat flaps: one for the cat and one for the kittens, which I love.

S.C.: That was Newton?

N.G.: Whether he did it or not, I don't know, but he is reputed to have. It's a John Aubrey legend. Newton was out there on the edges of science when nobody knew what the rules were. The joy of "Strange & Norrell" is that you have practical practicing magicians. One of the reasons science-fiction people liked that book was that it could easily have been about a lost science.

S.C.: You get there, to the rational voice, by having everyone argue with everyone else. If you assume magic existing as a technology, then obviously, as with any other body of knowledge, there will be hugely differing views. Once you have them all arguing about it with each other, it sounds very rational.

N.G.: All you have to do is spend any time around any scientists or academics to discover that they all disagree with each other and believe that their way of doing it is the only right and true way and that nobody else knows anything.

Both of you have very distinctive approaches to writing fiction with fantastic elements, so much so that I almost hesitate to call it fantasy, because by now the term is one many people associate with faux-medieval epics.

N.G.: It's a big word. I like to use "fantasy" to include everything else, too.

You mean conventional realism?

N.G.: Yes, because you're still making it up. Unless you're writing about actual real people who really do exist and what they do day to day and then do not decide which bits you'll emphasize, that could be realism. I mean, if you're running webcams and just writing up everything, that might be realism, but anything else ...

What about all the association with all those Tolkien imitators?

N.G.: That's so recent. One of the things I tried to do in "Stardust," and Susanna did do in "Strange & Norrell," is write a book for which there's an absolutely solid tradition in English literature, but it predates the idea that there was a part of the bookstore marked "Fantasy." When Tolkien published "The Lord of the Rings," those were books, published as books. There weren't "Fantasy" shelves because there was no genre.

S.C.: The fantasy we're both writing is drawing not just on the things that came after Tolkien, but on the whole of these things that came before. We're most interested in the things that came before the genre -- that's really it.

N.G.: Once people realized there was a genre, they started "doing" other people, doing Tolkien. They became faint photocopies. You get these great big books which are set in a medieval kingdom that is basically somebody's impression of what they liked about Tolkien, combined with what they enjoyed about playing Dungeons and Dragons as a high schooler. That's not what we're doing.

Still, you wind up being lumped with it because of the genre label.

N.G.: I don't know that there's any way around that besides market forces. I read a review yesterday in Bust magazine, which I'd picked up in a supermarket. I used to quite like it, but it looked like it had been bought by somebody and completely overhauled. They had some reviews in the back, and I said, "Oh look, here's a review of Kelly Link's new book. I wonder what they say." And what they said was that the book was really horrible because it was filled with things that were made up, zombies and things and a handbag with a world in it, and how could this possible relate to anybody's life? It was basically a review written by someone who could cope with neither similes nor metaphors.

Are either of us fantasy writers? I don't think so; we're both writers. But we make things up, and I like the privilege of being allowed to make anything up.

S.C.: It's about imagination. Jay McInerney did this interesting response in the Guardian newspaper to V.S. Naipaul saying that fiction is dead. It was quite good as far as it went. But there's this assumption in what he said that what you're writing about is the world now and that the important thing is to examine the world now. I kind of think, Why? Shakespeare didn't think it was important to write contemporary Elizabethan plays. Dickens tended to write about the society 50 or 20 years earlier. It seems to me that what writers are supposed to do is use their imaginations. Imagination is one of the most important things we have.

Shares