Shirin Ebadi's new book, "Iran Awakening: A Memoir of Revolution and Hope," opens with a chilling scene that underlines just how hazardous her human rights activism has been. In the fall of 2000, Ebadi, one of Iran's leading reformist lawyers, represented Parastou Forouhar, whose parents, dissident intellectuals, were butchered by government assassins. Their killings, part of a string of murders of regime critics carried out by the Ministry of Intelligence in the late '90s, were perpetrated with particular sadism -- the aging couple were stabbed repeatedly and then hacked to pieces.

In 2000, some of those involved in the murders were finally brought to trial. "The stakes could not be higher," writes Ebadi. "It was the first time in the history of the Islamic Republic that the state had acknowledged that it had murdered its critics, and the first time a trial would be convened to hold the perpetrators accountable."

The victims' lawyers were given 10 days to review massive stacks of government files on the case. Recalling an afternoon bent over the dossier, Ebadi writes, "I had reached a page more detailed, and more narrative, than any previous section, and I slowed down to focus. It was the transcript of a conversation between a government minister and a member of the death squad. When my eyes fell on the sentence that would haunt me for years to come, I thought I had misread. I blinked once, but it stared back at me from the page: 'The next person to be killed is Shirin Ebadi.' Me." As she recounts, she didn't have time to process the shock, because she needed to keep working. "Only after dinner, after my daughters went to bed, did I tell my husband. So, something interesting happened to me at work today, I began."

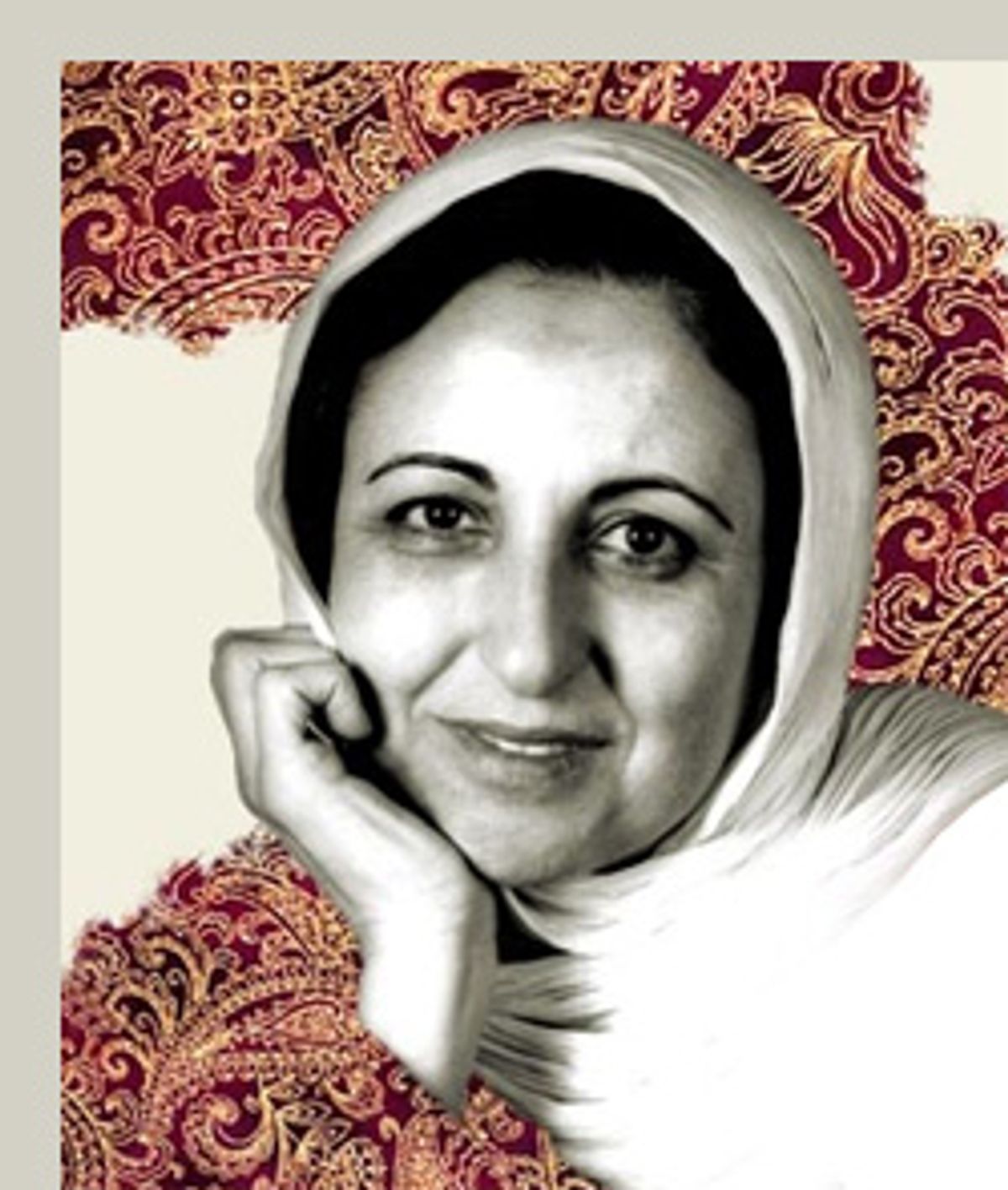

Neither death threats nor incessant harassment were ever able to stop Ebadi, 59, from challenging the Iranian regime on behalf of its most beleaguered citizens, and in 2003, her advocacy for Iranian women and human rights activists earned her the Nobel Peace Prize. In her often fascinating memoir, she tells of fighting for justice in a country where the rule of law has disappeared, replaced by a brutal, arbitrary absurdism worthy of a Persian Kafka.

Like many liberal intellectuals, Ebadi hated the shah and supported Iran's Islamic revolution, but it quickly turned on her. While only in her 20s, Ebadi had become one of Iran's first female judges. Once Ayatollah Khomeini took over, the same revolutionaries who had previously sought her support decreed that women jurists were un-Islamic. "In a cruel bureaucratic shuffle, I was appointed secretary of the same court I had once presided over as a judge," she writes.

No matter how many indignities she suffered, Ebadi refused to leave her country, eventually building a pro-bono law practice to represent the regime's victims. One of her most perverse cases involved the family of Leila Fathi, a young girl who was raped and murdered by three men. One of the men committed suicide in prison, and the other two were sentenced to death. Under Iranian law, though, a woman's life is worth only half that of a man's. "In this instance, the judge ruled that the 'blood money' for the two men was worth more than the life of the murdered nine-year-old girl, and he demanded that her family come up with thousands of dollars to finance their executions," Ebadi writes. The family ruined itself trying to raise the money; both Leila's father and brother were reduced to trying to sell their kidneys.

Ebadi waged both a legal and a media campaign on behalf of Leila's family. She didn't win them any measure of justice, but she focused both national and international attention on the regime's misogynistic abuses, taking great risks to do so. "We lived with daily examples of even prominent grand ayatollahs who had been defrocked (unheard of in Shia Islam) or placed under house arrest for speaking out against executions and harsh forms of criminal punishment, such as the chopping off of hands," she writes.

Ebadi would eventually be imprisoned, and her life was repeatedly endangered. But her determination to change Iran from within hasn't wavered. When the reformist President Mohammad Khatami was elected in 1997, many hoped for a loosening in the Iranian regime. "For a few stretches during the years of 1998 and 1999, the country experienced a flowering of open debate and freedom of the press that some optimistic souls called a Tehran spring," she writes.

The optimists have since been disappointed. Last year's election elevated the hard-line Mahmoud Ahmedinajad. Iran is now locked in an escalating confrontation with America over its nuclear program, and the government's rhetoric is militant and apocalyptic. In a despairing New York Times profile, Abbas Abdi, one of the hostage takers at the American embassy who later became a reformist, said the reform movement no longer exists. But Ebadi says she still believes that democracy will come to Iran from within, as long as America doesn't try to bomb it into being.

Salon spoke to Ebadi at her hotel during her recent visit to New York. A small woman who doesn't cover her hair outside of Iran, she spoke through a translator. Throughout, her voice was even and her manner impassive except when she was talking about the plight of Iranian women. Then she would softly, almost unconsciously pound her fist on the table.

In "Iran Awakening," you write that you didn't know how winning the Nobel Prize would affect your ability to work -- whether it would afford you a measure of protection, or give the authorities new motivation to crack down on you. How has your situation in Iran changed since then?

Working in the field of human rights is never easy. I already had difficulties before getting the prize. I had been in prison, and on several occasions they wanted to murder me. I'm used to getting threatening letters.

After I got the prize, my situation did not change inside the country. When I won, the radio and television -- the state radio and television -- did not even want to announce the news. It was only 24 hours later that one of the channels on TV -- at 11 p.m. in the evening, when practically everybody goes to bed -- announced the news. And then that was it.

So I won't say getting the prize has made things easier for me inside the country, but obviously at an international level, things have become much easier for me. Because of this my voice is better heard at the international level.

Has the situation for women in Iran changed under Ahmadinejad?

The situation for women is not good in Iran, unfortunately. But that doesn't mean it was better before Ahmadinejad. I can give you several examples of our laws. A man can have four wives, and he can divorce his wives without giving any reasons. But getting a divorce for a woman is extremely difficult, and in some situations impossible. The value given to the life of a woman is half that given to the life of a man. And on matters of testimony, the testimony of two women is equivalent to the testimony of one man. When a lady is married and she wants to travel, she has to have the written authorization of her husband in order to get her passport and the right to travel. But these are all laws that precede Ahmadinejad.

In your book, though, and in other stories from Iran, it seems as if the enforcement of such laws and the day-to-day persecution of women changes depending on the political situation.

During the reformist government, two laws were changed in favor of women. One of them was about custody rights for women. It used to be that after a divorce, the custody of sons until the age of 2, and the custody of girls until the age of 7, was with the mother, and then after they had reached that age, they would be taken away, if necessary by force, and given to the father. Obviously, women were very much protesting against this law. The answer of the government was systematically that this is Islamic law, and we cannot change it.

But then the women kept on fighting, and when I got the Nobel Prize and came back to Iran, about a million people were there expecting me at the airport, and most of them were women. When they came to welcome me so overwhelmingly, they wanted to show one thing to the government -- they wanted to demonstrate that they were not satisfied with the legal status of women in Iran. And the government got scared and changed the law.

In the book, you write about how, after the revolution, the sudden legal inequality between you and your husband made you resentful and caused tension in your marriage. Your husband agreed to a progressive solution: He signed a "postnuptial agreement" giving you the right to divorce him at any time and retain custody of your children. But he is the exception -- most husbands wouldn't do that. So how does inequality affect Iranian relationships?

What happens usually is that when people are to be married, they add a number of conditions in their contract so that this inequality disappears. For example, my daughter Negar was married last week. When she was getting into the marital contract, one of the conditions was that she will be free to walk out of the marriage whenever she wants. So this is something that's authorized -- you can add conditions to your contract. But that's not sufficient. I think the law should protect all women.

One of the most interesting things that I learned from your book is that women now outnumber men in Iranian universities, and that this is an inadvertent consequence of the Islamic revolution. You write, "If the universities had been dens of sin in the shah's Iran, what were they now? Rehabilitated! Healthy! There was no pretext left for the patriarchs to keep their daughters out of school, and they slowly found themselves in classrooms, and away from their parents in dormitories in Tehran." Now there's a huge wave of educated Iranian women. When do you think it will finally crest, and these women will start demanding much more freedom?

It is already bearing fruit. I talked about this law on the custody of kids. I think this is the beginning, and women will be getting more in the future.

In February, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice requested $85 million for a plan to promote democracy in Iran, partly by funding reformists and dissidents. Has this increased the suspicion and harassment of reformists in Iran?

I think that this is not in favor of democracy in Iran. The people who live in Iran will never dare accept any foreign money, because this would be the first proof of treason.

In January, you co-wrote an Op-Ed in the Los Angeles Times saying that America was undermining Iran's "fledgling democratic movement" by demonizing the country. As the conflict between our governments heats up, what effect has it had on your country's reformists?

It's very well known that any time a country is under threat from outside, the government uses it as an excuse and starts talking about the necessity of preserving national security, and therefore individual liberties suffer.

A recent article in Time magazine suggested that the administration might ratchet up the conflict in order to get Americans to rally around the president again. How worried are Iranians about the possibility of an American attack?

Some people are worried. People are very critical toward the government, but I think that if there is an attack against Iran, people will forget about their criticism, and they will rally with the government. Any attack on Iran will be good for the government and will actually damage the democratic movement in Iran.

Even after Iraq, there are still some Americans who insist that many Iranians want our country to liberate them, and that they'll support us if we try to institute regime change. What would you say to them?

Again, the people of Iran are very critical of their government, but they will not allow a single American soldier to step foot in Iran. The problems between Iran and America have only one solution -- direct negotiations between the two countries.

Do you see similarities between the fundamentalists in America and those in Iran?

Once in a while I have the impression that what Mr. Bush says is very much like what Mr. Ahmadinejad says. For example, when Mr. Bush says he has a mission from God to settle the problems in the Middle East. Mr. Bush sometimes wants to bring democracy through the use of force, like the government of Iran wants to push people by force into paradise.

The other day, the New York Times ran a profile of one of the hostage takers at the American embassy in 1979 who later became a reformist. He was very pessimistic about Khatami's failure to bring more freedom to the country, and said that the reform movement no longer exists. Do you agree? Is the reform movement dead?

I don't agree with that. People are unhappy with the situation in Iran, and they're also very tired of all sorts of violence. You should not forget that during the past 27 years, the population has known one revolution and eight years of war with Iraq. So there's no other way than reform.

What will it take to bring democracy to Iran? Will there have to be another great outpouring, like the mass demonstrations that led to the fall of the shah?

That was a revolution. But I don't think the 21st century is the century of revolutions. It's the century of reforms. It should be done in an amicable way, just as the women were able to change the custody law, although the government had resisted any change for 20 years, and had always insisted this is an Islamic law and we simply cannot modify it.

If the people support the goals of the reformists, how did Ahmadinejad get elected?

Because the electoral law says that any candidate who puts his name forward must be approved by the Guardian Council. Any person who is slightly critical of the government is considered not competent. More than 90 percent of candidates are considered incompetent for electoral purposes.

Let me give you a comparison that will show you how Mr. Ahmadinejad was elected. We have a population of 70 million. Forty-nine million can vote. Mr. Khatami was elected with 22 million votes. Mr. Ahmadinejad, during the second round of the elections, when all the other competitors had been eliminated, got 14 million votes.

Why do you think fundamentalism has been on the rise in so many countries?

It is fanaticism -- that's the source. I'll tell you an old Iranian tale. God was sitting in seventh heaven, and truth was like a mirror in the hands of God. This mirror fell from seventh heaven to earth, and it was shattered into little pieces, and every piece went into a house. All people got a little piece. So everybody has a piece of the truth. Therefore, you have as much truth and rights as I do. If you talk in this way, and prune this idea, then there won't be any problems among people.

Shares