It's not that Americans cheat any less than the French -- in fact they cheat a bit more -- it's just that when Americans do cheat on their spouses they feel so damn guilty about it, it's a wonder they ever had the affair at all. To Americans, "it's not the cheating, it's the lying." And couples who don't break up over infidelity often turn to therapy and support groups, which, ironically, frequently encourage cheating spouses to reveal every last detail about their illicit relationships to regain the trust that was lost when their pants came off in the first place.

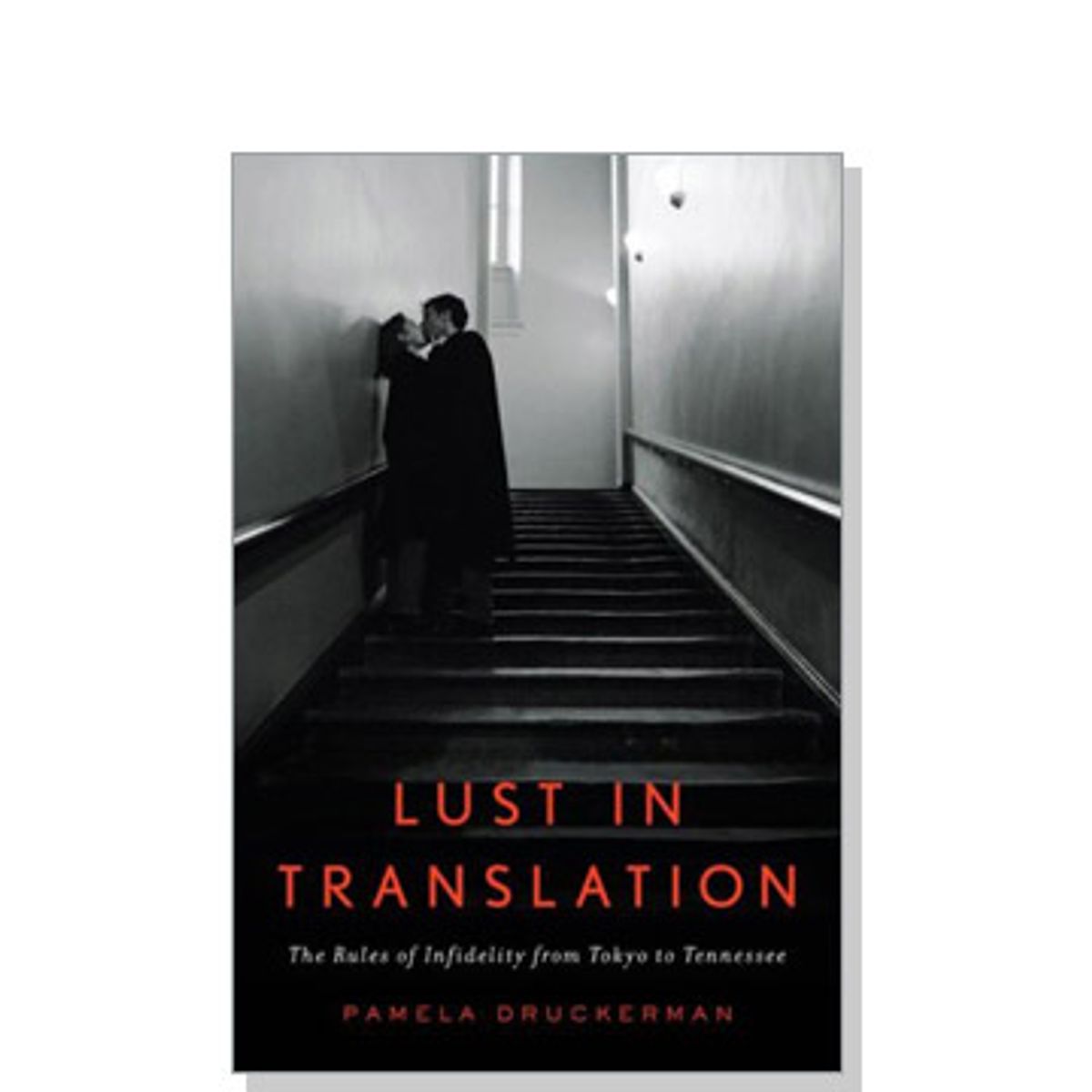

So goes the American infidelity script, as it is unraveled by former Wall Street Journal reporter Pamela Druckerman in her new book, "Lust in Translation." Druckerman traveled to 10 countries to investigate, as her subtitle puts it, "The Rules of Infidelity From Tokyo to Tennessee." Through dozens of interviews with middle-class urbanites, the author, who devotes a chapter to each country she visits, debunks -- and sometimes confirms -- national myths, stereotypes and pastimes. Along the way she discovers that people in poor countries tend to cheat more than people in wealthy countries, that in America men and women under 40 have nearly equal rates of infidelity, and that everyone, all over the world, sometimes gets hurt. While the evidence she presents is primarily anecdotal and backed up by statistics that even she admits are imperfect, Druckerman still manages to give a structure to national sexual habits, a kind of cultural script for how affairs are supposed to go -- even if they don't always go so smoothly.

Salon called up Druckerman, who now lives in Paris with her husband and daughter, to talk about cheating, cultural mores and why Americans have a harder time getting over an affair than their foreign counterparts.

What made you want to write a book about adultery?

Adultery is a pivotal issue -- especially for Americans, but in all cultures -- because it's at the crossroads of public and private life. So you have legislation about it, you have laws dictating sexual behavior, but it's also ... the most secret sex that people have. Americans have gotten more permissive about practically every mainstream sexual issue in the last 30 years -- from divorce to homosexuality to cohabitation to premarital sex to having kids out of wedlock. But our thinking about adultery has become even stricter since the '70s. So there is something special going on in American life about fidelity, and I wanted to look at what that was. It's kind of the last great sin in America. Last year there was a Gallup-poll ranking of what Americans found morally [disturbing], and adultery was considered worse than polygamy and human cloning.

Why do you think we feel so strongly about it?

I think one of the reasons why we've gotten stricter about adultery is because divorce has become a lot easier. When it became easier to divorce, people started expecting a lot more from marriage and they were less tolerant of any violation of the romantic ideal. So that's where you get the idea that if you cheat on me, even if it's a one-night stand, it's over. That is a powerful cultural idea in America, even if people don't always carry it out.

What were some of your most surprising discoveries?

I wasn't doing a scientific study; I was going around the world and spending a few weeks in each place and interviewing whoever would talk to me. So I wondered if that would give me a fair enough sense for how people really behave. What I found -- and this surprised me -- was that in each country there was a lot of variation in the way people behave, but everyone has a few common ideas about how affairs ought to go, when they are justified, how obliged the people who are cheating are to each other, and how affairs should end. There's a whole cultural script, rules about how to conduct your infidelity. Of course, nobody follows the script exactly. But I found that by talking to people about not just what they did, but what they thought about what they did, you can whittle out the story or the rules in each place.

For instance, in America a married man who is having an affair feels almost obliged to say he's in an unhappy marriage -- whether he is or not. As an American, I assumed that's what anyone in the world would do to justify cheating. But it turns out people in other places do things quite differently. In China I found that married men are supposed to praise their wives to their potential mistresses to show that they're good people, that they're good husbands. In America you seem like a real jerk unless you're in an unhappy marriage -- that's your excuse for cheating. [Another] thing that surprised me was that over and over again in America people who had cheated on their spouses told me they really weren't the kind of people who would have an affair. Part of the American script is to say that you're really not the kind of person who would do it. And the other thing Americans always said at the end of an interview was, "I really hope that by sharing my story with you, I'll help someone else." And no one else anywhere in the world said anything like this. They assumed that talking about their infidelity would be an act of public service.

Was there any one universal attitude among all the countries that you visited?

One thing I found was that everyone everywhere gets upset when their partner cheats on them. You hear there is this mythical country -- whether it's France or whether it's in Africa -- where the men run around and the women just don't care. But I didn't find that.

The one exception was probably Japan, where I found that women didn't mind so much if their husbands cheated, but they had to observe an elaborate set of rules about how they went about doing it, one of which was to be extremely discreet. So when Japanese wives found out, they were mad, not because their husbands had slept with someone else, but because they had been indiscreet about it.

You seem shocked that the French weren't as laissez-faire about adultery as you'd initially thought they would be.

Yes, I had this image of France as this place where husbands and probably even wives play around and it's just part of life -- everyone accepts it, it goes on, and no one makes a very big deal about it. The big example of this is the Mitterrand funeral photo. I thought, well, wow, they have a president whose mistress and illegitimate daughter showed up at his funeral standing next to his wife, that this is obviously a place that is at peace with extramarital affairs. And it turned out not to be the case at all. It turns out Mitterrand's second family had been a state secret for decades. He had been petrified that the public would find out about it. He had hired a special government team to tap the phones of any journalists that were going to reveal the fact that he had a second family. It was an inside secret and the public didn't know at all until less than two years before he died. And even then, the release of that [information] was carefully crafted. It turns out that French people don't cheat very much at all. They might be more tolerant of the idea of infidelity, but in reality they cheat pretty much exactly as much as Americans do, or even slightly less.

Were you surprised that Russia turned out to be the capital of cheating?

I knew Russians had a reputation for not being particularly rule-bound. But the extent to which they totally accepted infidelity very much surprised me. I later found an international poll that said that 40 percent of Russians say that extramarital affairs are either not at all wrong or usually not wrong. The percentage of Americans who say cheating is not at all wrong or usually not wrong is 6. So Americans are at the other end of the spectrum.

Along with geography, do economics play a role in shaping attitudes about adultery?

Definitely. It turns out that in America and other wealthy countries people are mostly faithful. The big divide is between rich and poor countries.

Did you come across a reason for those disparities?

Well, in many of the poor countries I visited there is this cultural story again that men have very powerful libidos and they can't be expected to control themselves -- and there isn't that same story about women. Another reason men in poor countries might cheat more is simply that they can. That is, they often have a lot more power than their wives, and cheating is one of the ways they express it.

You went into these interviews with American values, listening to these people talk about their own cultural script. Was it hard to understand where they were coming from?

I'm a journalist so I'm used to listening to a lot of people's different points of views, but there were definitely times when I thought, now you've gone too far. For instance, when I was in Indonesia I went to this town in the middle of the island of Java and met this foreign man who was Italian-Brazilian and had moved to Indonesia, converted to Islam hastily, and within the space of a couple of years married four different women, had 12 children with them. And then he was also having extramarital affairs because of the stress of all these young wives demanding things from him. Then he hit on me, and my friend who was interpreting! It was almost comical. Needless to say we said no.

I got the impression that oftentimes when you were talking to men, they took it as if you were almost propositioning them.

Sometimes people were very suspicious; they just assumed that if I was researching this topic it was something that I was interested in myself. One of the most embarrassing moments was not when I was in an exotic country, but interviewing these women in their 70s in retirement communities in Palm Beach. They all had had extramarital affairs and they were delighted to tell me about them. It was some of the best times of their lives. A lot of them married their affair partners and they felt none of the contemporary shame that we feel about cheating. This one woman, and this is not a woman you can exactly imagine in a sexual way, was describing to me how she used to perform oral sex on the guy she was having an affair with in cars in New York City after they would come out of nightclubs. It was like watching your grandmother talk about sex. It was very "Golden Girls."

Then there were also these Hasidic guys. One guy took me aside and wanted to tell me all about the laws of adultery, and Jewish law, and at a certain point I realized that he was giving much more detail than was required in describing the sexual acts that were and were not permitted in the Talmud.

Was that an uncomfortable moment?

Let's just say I got up and looked for the potato chips.

Do you think it's harder for Americans to deal with infidelity than in other cultures?

I think there are aspects of the American experience of adultery that make it much harder to get over. First of all, you have this idea that your spouse would never cheat on you and if he or she does, that means there is a tragic flaw in your marriage that can never be repaired. If that's your assumption, then when it happens, it's going to be especially devastating. Americans often told me that "once I discovered that my wife was cheating I realized that we had been living a lie and that our whole relationship was built on a false foundation."

You talk about America's "marriage-industrial complex" and the therapeutic idea that the cheater has to reveal everything to their spouse about the affairs to complete the healing process. Did you meet anybody for whom that strategy actually worked?

I can't say I did a scientific study, but no, I definitely didn't meet anybody who said, "now that I know exactly how many blow jobs my husband got from his mistress, I feel a whole lot better." But that idea that marriage ought to be this kind of transparent zone where nothing important is hidden is so powerful that as a quote-unquote solution it has a lot of resonance.

You say one of the reasons you wrote this book was because when you were working in Latin America all of these married men propositioned you, and you found it "repugnant." After writing this book do you think you've become more tolerant of that behavior?

It's funny. I think there is a puritan part of me that will never go away. So when I hear about cheating in the lives of people I know personally, I'm still a little bit surprised ... But now that I have the statistics on how many Brazilian men cheat, and how many Peruvians cheat, and Dominicans, I think I would have a more scientific perspective. Part of the American way of thinking about affairs -- and I'm including myself in this -- is to think the adulterer isn't just doing something wrong, he's also a bad person, a bad guy, and there's no telling what other bad things he could do if he could cheat. I think my perspective has changed in that respect.

Shares