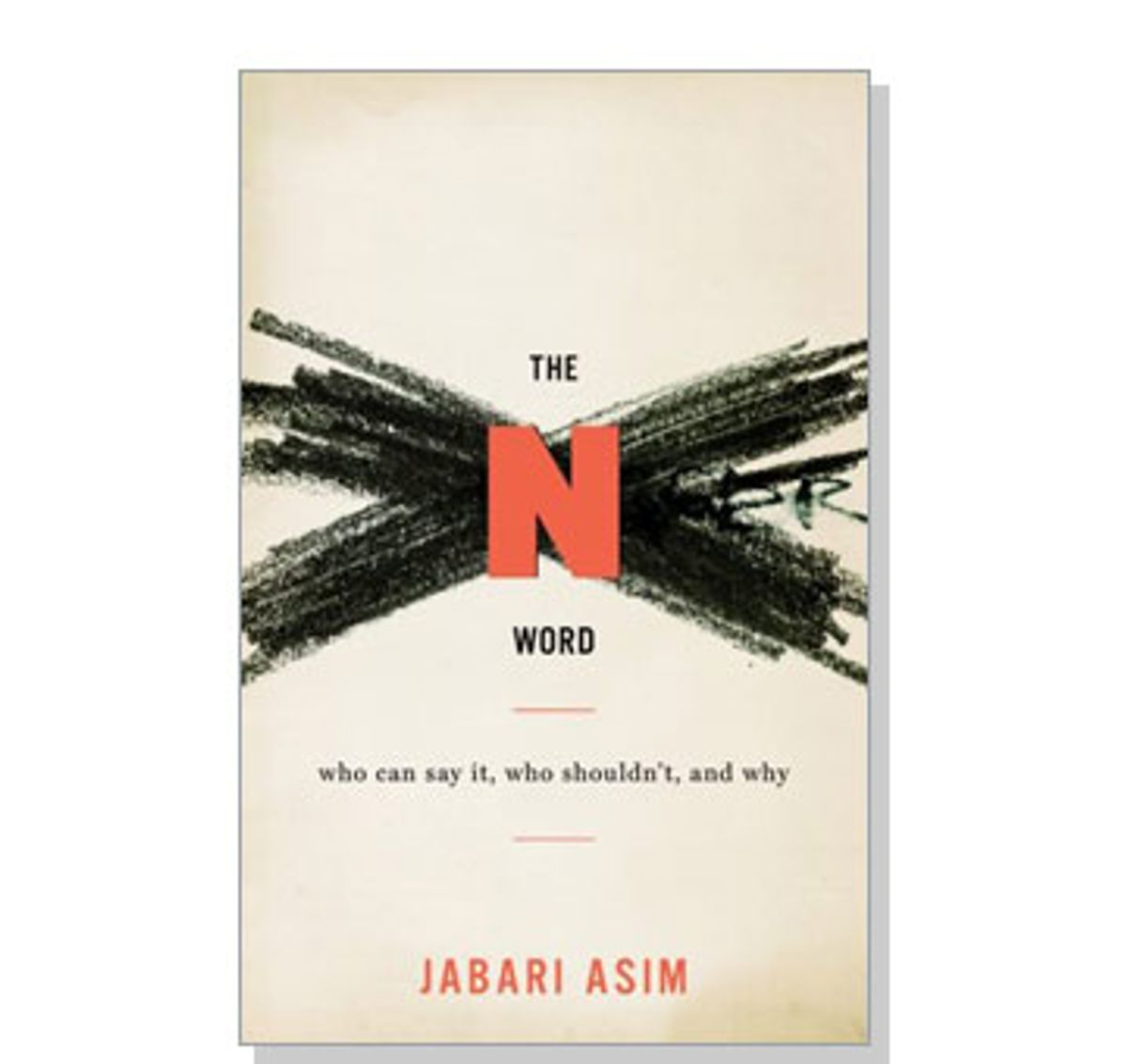

When faced with increasing criticism for his "nappy-headed hos" commentary, Don Imus deftly flipped the conversation, suggesting that he found inspiration from the world of hip-hop. The conversation quickly and disingenuously turned into a debate about the role of hip-hop in spreading sexist and vulgar language, as if scripted by the folks at CBS Radio and NBC. Central to this discussion was the sense that a double standard exists where black male rappers are permitted to call women "bitches" and "hos" and are subject to little scrutiny while old white men like Imus face a public crucifixion for what some deem a bad joke. Author and longtime Washington Post Book World editor Jabari Asim had heard all of these arguments before in relation to the use of the word "nigger" in American popular culture. In his new book, "The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn't, and Why," he places the focus squarely on American society and the undercurrents of white supremacy in our culture. Conceived long before the Imus story broke, "The N Word" provides a needed perspective on the controversy. Asim spoke to Salon about the use of the word, from "Uncle Tom's Cabin" to N.W.A. to Imus, and set some boundaries for who can say it -- and where.

One of the things I thought about while reading "The N-Word" was Ralph Ellison. In his review of Leroi Jones' [Amiri Baraka] now classic "Blues People," Ellison quipped that the "tremendous burden of sociology that Jones would place upon the body of music is enough to give even the blues the blues." In that same vein, the amount of historical research and literary history that you present throughout "The N-Word" fundamentally demystifies the word.

I had my preconceived notions about the word, but I tried for them to not be a guiding influence. I wanted to be as open-minded as I could honestly be. I wanted to look into it and see where it led me. Let me just wander around in the culture, and I'm a greedy consumer of culture. Bakari Kitwana said to me that I'm obviously a bibliophile, and that's the one area where I had some confidence, so naturally I leaned on that -- a lot more than I could lean on music.

What was the conversation like with your publishers about the title of the book? Was the title your idea?

That was the working title from the beginning. I thought that was a marketable title because everybody knows what the N-word is. Where we went around the bend a little bit was on the subtitle, which was originally "race, metaphor and memory," because I kept thinking of the N-word as a metaphor for these various ideas involving citizenship and black inferiority, in particular. Later, my editor and I agreed on "a short history of racism" because ultimately the book is about white supremacy. Then the marketing people said that it wouldn't work, so they came up with the current subtitle. I didn't like it at all, but they said it was the difference of having the book displayed with the cover out front as opposed to just the spine. What it leads to, as the marketing people well knew it would, is that I've done about 50 radio interviews.

One of the things that is refreshing about the book is your knowledge of literary history. You employ all of these examples of the N-word's use in literature, and given the role that literature played in America's development, you could make the point that the stuff that we see circulating in popular culture today is really not much different from the literary narratives circulating 200 years ago. How is the conversation different now than the one that surrounded "Uncle Tom's Cabin," given who had access to literacy then? How does the access that we all have to popular culture now impact our sense of content that we might deem racist?

The message hardly changes at all. I have a section in the book where I talk about those early "niggerologists" of the 19th century, who lectured at Harvard and these prestigious scientific academies but immediately spawned less-educated imitators who handed out pamphlets instead of texts. And this is what the working class was exposed to. So I argue that "niggerologists" spoke down from the educated classes and at the same time rose up from the uneducated classes. At the same time, in the early American literature, those writers were really motivated to establish an American identity because they had a complex about Europe's cultural influence and Europe's rich history -- they had the same motivation of those early scientists. I thought it was significant that all of these attempts -- legislative, academic, literary -- all of these attempts to establish an American identity revolved around and depended upon the degradation of black people.

Were you conflicted at all when the conversation inevitably had to go to hip-hop? I mean, I imagine that there were all kinds of pressures around you as you turned in the manuscript to make it sexier, and sexier at this moment includes an indictment of hip-hop. But you dealt with hip-hop as it presented itself in a logical way. I thought it was interesting that you could take a so-called conscious rapper like Mos Def and so-called gangsta rappers like N.W.A. and acknowledge that there was a very real consciousness, especially in the case of N.W.A., behind how they employed the N-word.

I didn't set out to do that. I've never had strong emotions about hip-hop, one way or the other. I've never been a hip-hop head, though members of my generation are. I never felt that it spoke to me in particular or told my story. I thought that quite a bit of the criticism of hip-hop -- and I say this as an outsider and a resolute non-expert -- is superficial, in that it comes from people who perhaps have never sat down to listen to a hip-hop recording. Criticism, if it's gonna serve any constructive purpose, must be deeply informed. So I had to listen to all that N.W.A. and I had to read those lyrics. And so as I listened to it. There were songs that confirmed what I had heard about these guys -- this is some awful stuff. And then there were other songs that seem to meet all the criteria. My hastily assembled yardstick for the use of the N-word is that I think art is sacred and you just don't respond to it the way you respond to other things. Secondly, if the use of the N-word advances our understanding of the culture in some way, then to me it is valid. N.W.A.'s lyrics easily meet that criteria. People talk about hip-hop spreading the N-word through the culture, but I take pains to point out that popular culture has always spread the N-word. There is serious precedent -- in the 1920s and 1930s, you went into a white middle-class home and the N-word was everywhere. It was on the shelves, it was in the cookbooks, the sheet music on the piano, the toys children played with. Let's not talk about hip-hop introducing this word in some new and unprecedented fashion. The only difference is that hip-hop exists during a period of high technology and spreads these things a lot faster. But let's not pretend that hip-hop has somehow confused white people regarding the use of the word. I think that's a very disingenuous argument.

Toward the end of the book you mention that you are ultimately concerned with the use of the word in the "public square." Do the contours of that public square change, particularly when we talk about public airwaves? Does it make a difference to you what that public square looks like at 3 in the afternoon versus 11 at night? Do you give artists and commentators some leeway, based on those different contours?

There are obviously different ramifications with regards to FCC regulations and those amorphous broadcast standards, which networks seldom use, but immediately make Don Imus' firing justifiable. I think that for stuff that is broadcast, the consumer has a choice. So you broadcast this into my home and I find it offensive, I can change the channel. I can turn you off. If we're sitting on the train and you're using that kind of language, I don't have any options. I'm exposed to it against my will. It is not quite an analogous situation. And in the public square, I think that's where expectations of courtesy and civility should play a greater role.

Shares